Yad Vashem Photo Archives 813/3

Excerpt from: "Ghetto Kovno - Religious Life in Slobodka"

Director: Itay Ken Tor

Producers: Noemi Schory, Liat Benhabib, Liran Atzmor

Production company: Belfilms Ltd.

It was illustrated by Horst Rosenthal, a 27 year-old German Jew interned in the camp. In September 1942 he was deported to Auschwitz, where he was murdered.

Courtesy of Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine, Paris, France

In March 1943, 18 year-old Margot Fink and her family were caught while living in hiding in Amsterdam. Margot was separated from her family and deported to Auschwitz, and then on to Reichenbach. In February 1945, she was forced on a death march and was liberated in May. After the war, Margot discovered that her parents and younger brother had been murdered.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Margot (Fink) Berlin, Haifa, Israel

Yekutiel’s second son, 12-year-old David, was sent to his grandparents in Hungary in an effort to save him. Yekutiel fashioned the chessmen from pieces of wood that he found in the yard of the house where they were hiding. After the liberation, Noah and his parents returned to Bratislava, and discovered that David had been deported Auschwitz, where he was murdered.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Noah Stern, Mevasseret Zion, Israel

When Eva Movdal and her family were deported from Transylvania, 8 year-old Eva took her doll Gerta with her. Eva and her mother were sent to prison. Her father was in a different prison, but managed to organize a safe haven for them in the Romanian embassy in Budapest, where they were transferred. After the war, she learned that her father had been killed while attempting to escape.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Éva Modvál-Haimovich, Israel

The Shofar was made in anticipation of Rosh Hashanah 5704 (1943) by Moshe (Ben-Dov) Winterter from the city of Piotrkow, Poland, who was an inmate in the camp and worked in the metal workshop of the armaments factory. The idea of making a Shofar was initiated by the Radoszyce Rabbi, Rabbi Yitzhak Finkler, who was a prisoner in the camp. He believed that the inmates must carry out the commandment to blow the Shofar, and thus awaken God's mercy, especially at this fateful time. In spite of the great danger, Moshe Winterter made the Shofar and brought it to the Rabbi on the eve of the holiday. Word spread and the inmates gathered together for prayers and to hear the sounds of the Shofar.

Yad Vashem Collection, Jerusalem, Israel

Donated by Moshe (Winterter) Ben-Dov, Bnei Brak, Israel

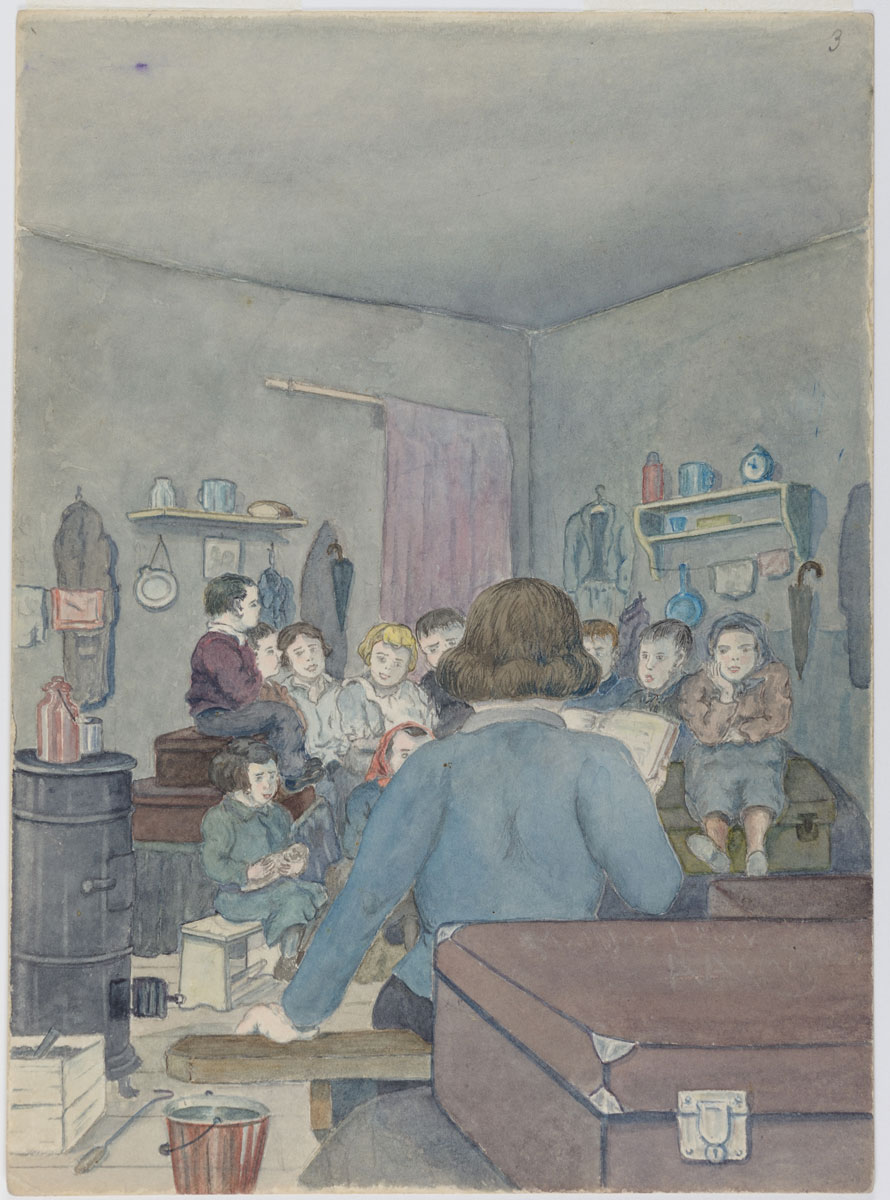

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum

Gift of Paul and Hilda Freund, Jerusalem

Gift of the Prague Committee for Documentation, courtesy of Alisa Shek, Caesarea

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum

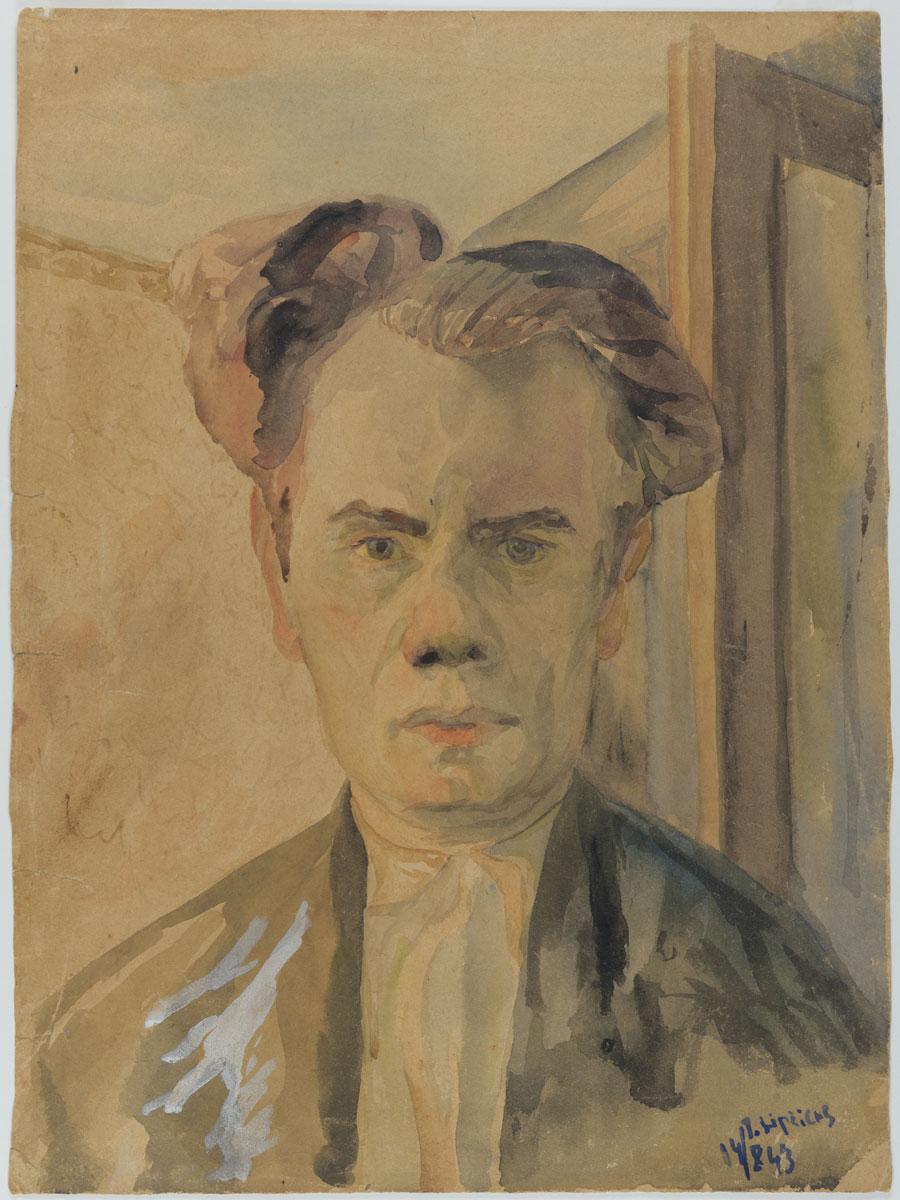

Watercolor and India ink on paper

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum

Gift of Otto Ginz, Israel

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

Gift of the Artist

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum

During the war, European Jewry was faced with a constant struggle for its very survival. Yet even under such terrible conditions there were those whose acted in ways that went beyond the necessities of human existence: they risked their lives - deliberately and intentionally - for high causes, including educating their children, maintaining religious values and traditions and sustaining centuries-old cultural activities. Unfortunately, not all those who succeeded survived the hell that was the Holocaust, but their deeds themselves bear witness to power of the human spirit.

One phenomenon that testifies to an impressive level of spiritual survival is the effort made by Jews to document their lives in the ghettos and the camps. Artists and intellectuals, children and ordinary people, wrote and drew in order to document the fear and crisis that pervaded Jewish society. These activities were not only helpful in allowing many to rise above the humiliations and injuries they suffered, but also sometimes alerted the free world to the reality of their lives. Even in the camps themselves, one finds evidence of activity through which the prisoners could - if only in their imagination - transcend the barriers of their status and of the surrounding camp environment. While only a few took part in these activities, their importance lies not in their quantity but in the strength of spirit needed for their realization within the reality of persecution and humiliation.

Despite the predatory reality endured by the Jews of Eastern and Western Europe, many people mobilized to assist those weaker than themselves, establishing mutual aid and welfare organizations. In the camps, helping others often became a matter of life and death, accompanied by difficult moral dilemmas. By helping another person - whether with food, clothing or work - the individual potentially jeopardized his own ability to survive. However, many Jews placed themselves in grave danger in order to save the lives of others.