Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 7F02

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 4613/518

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 4613/661

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 8B04

Standing on the right is author and journalist František Kraus. Kraus survived the Holocaust.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 933/8/27

Banknotes were issued in the Theresienstadt ghetto. When inmates received money from outside the ghetto, it was converted into “Theresienstadt currency”, which was effectively worthless.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Banknotes were issued in the Theresienstadt ghetto. When inmates received money from outside the ghetto, it was converted into “Theresienstadt currency”, which was effectively worthless.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

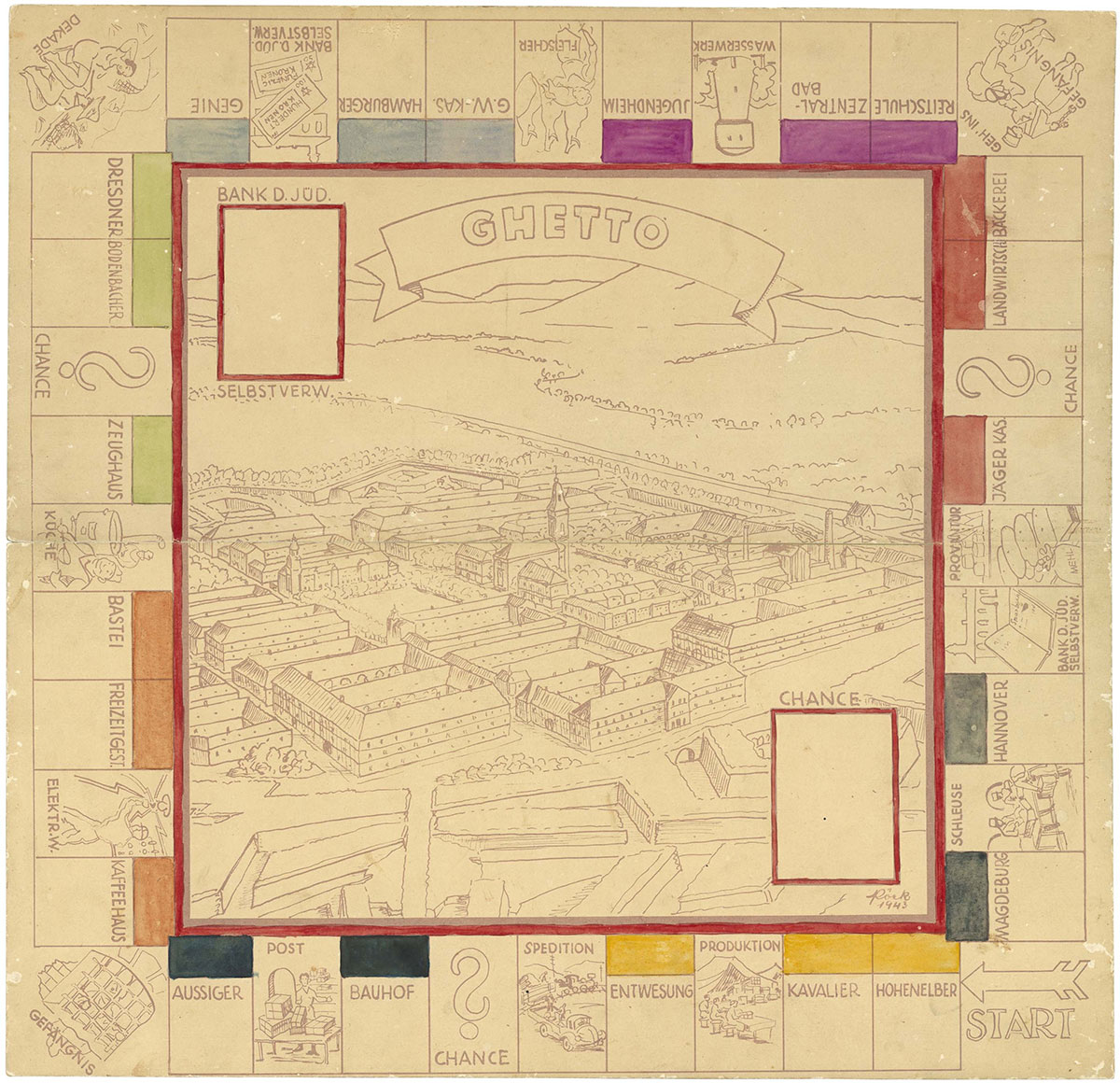

In addition to entertaining the children, it was intended to provide them with information about ghetto life. The board displays a drawing of the ghetto. Significant ghetto sites are stations in the game: the prison, the barracks, the fort, the warehouse, the kitchen, the deportees' absorption site and others. Those who were deported would often leave belongings with friends who remained in the ghetto, and thus, the Monopoly game was passed on to Pavel and Tomaš Glass in Theresienstadt.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Micah Glass, Ramat Gan, and Dan Glass, Jerusalem

In January 1943, just two months before Jiři’s Bar Mitzvah, the Bader family was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto along with the rest of the Jews of Kyjov. In light of this upheaval in their lives, it was impossible to celebrate Jiři’s Bar Mitzvah on time.In April 1944, when Jiři was 14, they finally marked the occasion in the ghetto youth club. In spite of the restrictions and difficult conditions, Jiři's family and friends prepared gifts for him: he received a prayer shawl in a cloth bag that was made from fabric remnants; an album illustrated by the talented caricaturist Max Placek with his life-story in words and pictures; and a leather wallet made in one of the ghetto workshops. Two months later, Jiři and his father Pavel were deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Vera (Bader) Weberova, Czech Republic

The doll apparently represents Alice Randt, who was deported from Hannover to Theresienstadt and survived

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

The doll apparently represents Arnold Rubin, a Czech inmate in the Theresienstadt ghetto who was sent from there to Auschwitz and murdered

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Vera (Bader) Weberova, Czech Republic

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Vera (Bader) Weberova, Czech Republic

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

Gift of the Prague Committee for Documentation, courtesy of Ze’ev and Alisa Shek, Caesarea

Gift of the Prague Committee for Documentation, courtesy of Alisa Shek, Caesarea

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum

Gift of the Prague Committee for Documentation, courtesy of Alisa Shek, Caesarea

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum

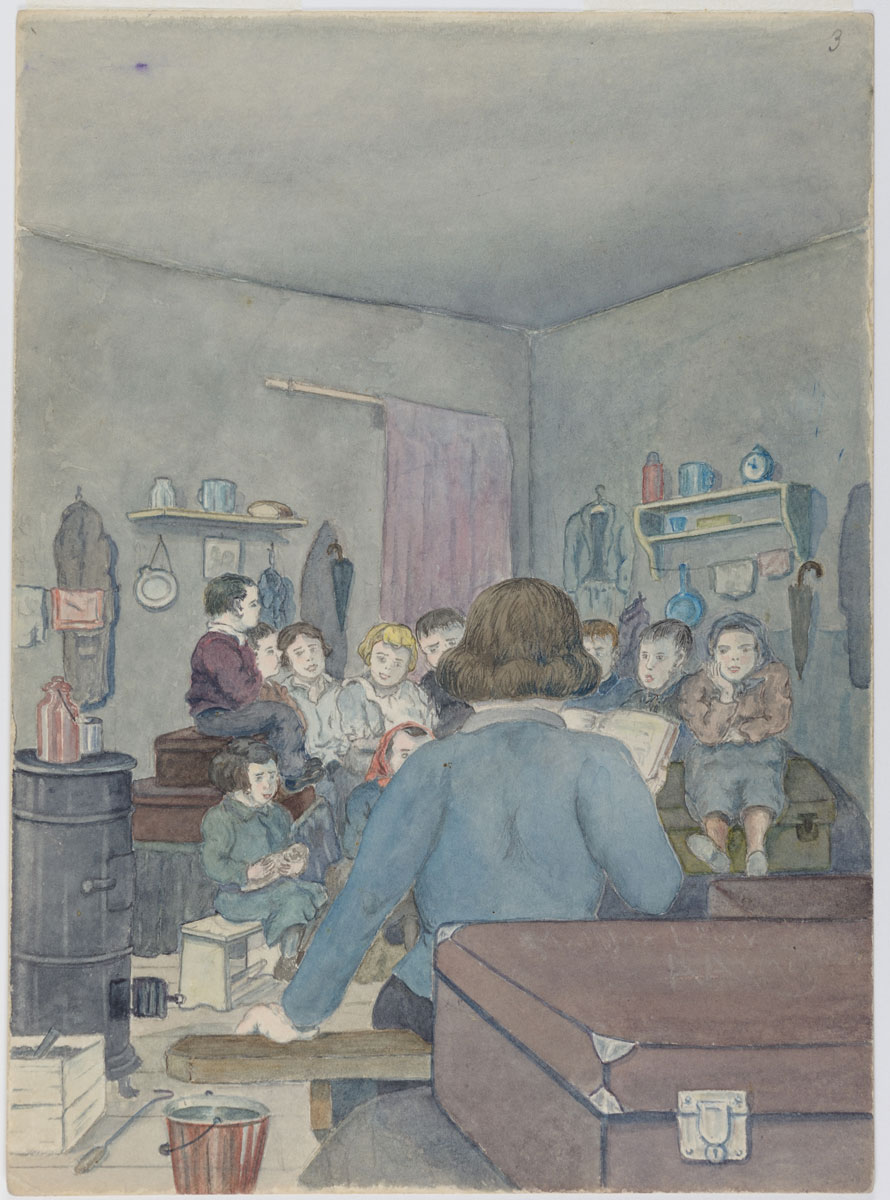

Watercolor and India ink on paper

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum

Gift of Otto Ginz, Israel

In 1941 the Nazis established a ghetto in Theresienstadt (Terezin), a garrison town in Northwestern Czechoslovakia, where they interned the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia, elderly Jews and persons of “special merit” in the Reich, and several thousand Jews from the Netherlands and Denmark. Although in practice the ghetto, run by the SS, served as a transit camp for Jews en route to extermination camps, it was also presented as a “model Jewish settlement” for propaganda purposes.

Internal life in Theresienstadt was administered by the Ältestenrat (Judenrat), headed by Jacob Edelstein. Despite severe congestion, food shortages and compulsory labor, the extensive educational and cultural activities in the ghetto reflected the prisoners’ will to live and their need for distraction from their plight.

When reports about the death camps began to emerge at the end of 1943, the Nazis decided to present Theresienstadt to an investigative commission of the International Red Cross. In preparation for the commission’s visit more deportations to Auschwitz were carried out in order to reduce the overcrowding in the ghetto. Fake stores, a coffee house, bank, school, kindergartens and the like were opened and flower gardens were planted throughout the ghetto. The commission arrived in the ghetto on June 23, 1944. Their meetings with prisoners were meticulously planned beforehand. After the visit the Nazis produced a propaganda film about the new life of the Jews under the auspices of the Third Reich. After finishing filming, most of the actors in the film, including almost all of the independent leadership and most of the children in the ghetto, were sent to the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The appalling overcrowding, sanitary conditions and malnourishment led to the spread of diseases amongst the population of the ghetto. In 1942, 15,891 people died in Theresienstadt, half of the ghetto’s population. More than 155,000 Jews passed through Theresienstadt until it was liberated on May 8, 1945; 35,440 perished in the ghetto and 88,000 were deported to be murdered.