Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4613/451

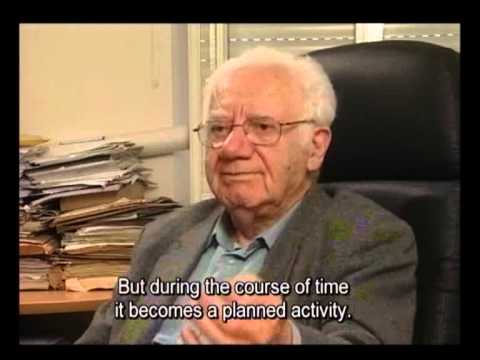

Excerpt from: Starvation and Soup Kitchens in the Warsaw Ghetto

Directed By: Reuven Hecker

Producers: Noemi Schory, Liran Atzmor, Liat Ben Habib

Production Company: Belfilms Ltd.

The Oneg Shabbat Archive is the most signficant collection of sources in the world documenting the Holocaust - sources that were created and gathered by the victims themselves during the Holocaust. The Archive is comprised of diaries and notes, memoirs, photographs, clandestine newspapers, monographs, letters and more - all of which are of inestimable value in the study of the living conditions, the creativity, the struggle and the murder of Polish Jewry in the Shoah.The Archive was named by its founder and director Emanuel Ringelbum. Ringelblum, a historian, teacher, social activist and visionary, was murdered in the Holocaust.

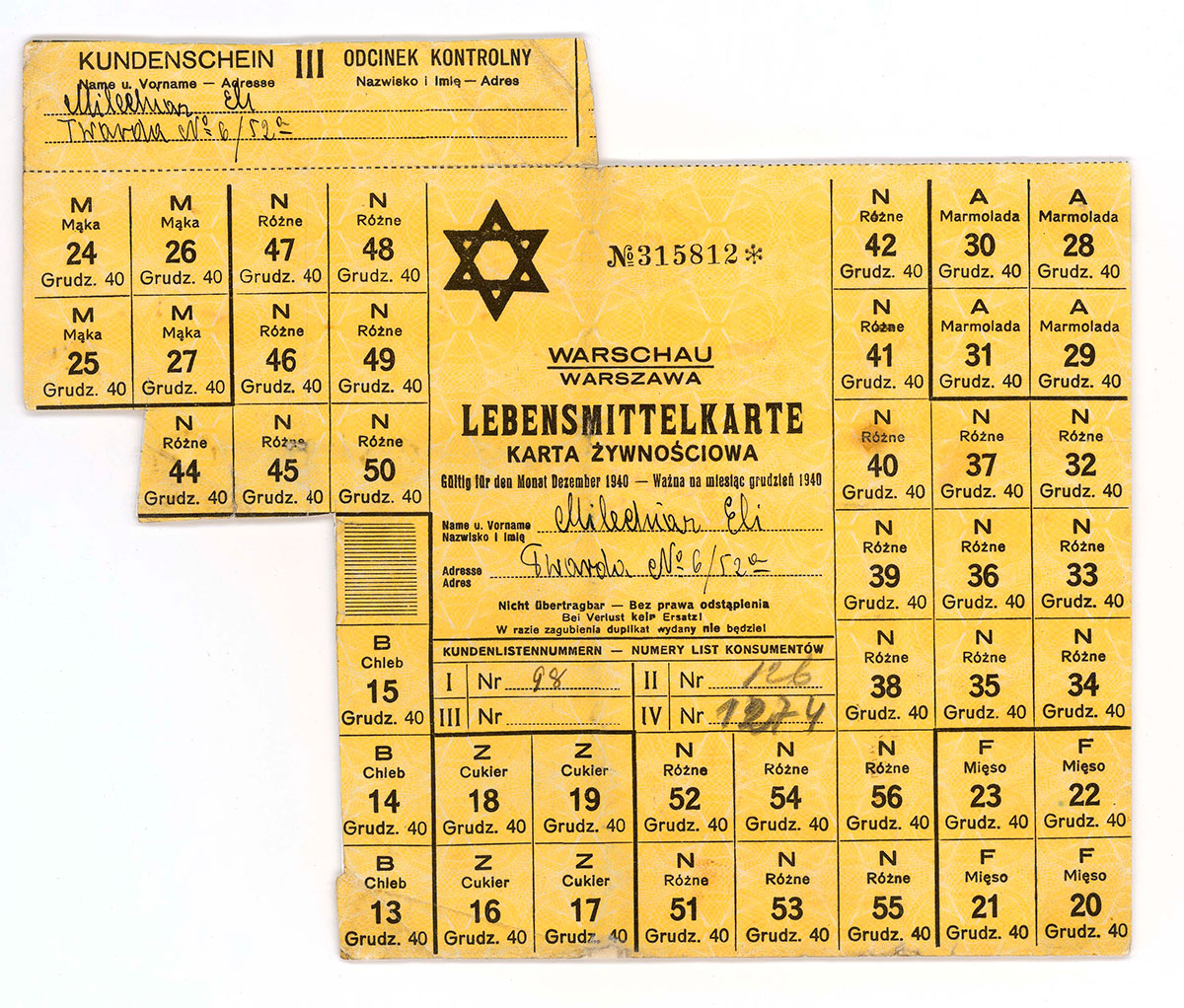

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Loaned by Żydowski Instytut Historyczny Instytut Naukowo-Badawczy, Warsaw, Poland

One day, Natalia, who helped smuggle children out of the ghetto, was injured. She sent a youth to the cellar to rescue her daughter. He put Zosia into a coal sack and carried her out on his back. Only when they were outside the ghetto did she realize that she had left her doll in the cellar.Tearfully, she insisted that they go back, “because a mother doesn’t leave her little girl…” They returned to the ghetto, retrieved the doll and managed to get out safely again.

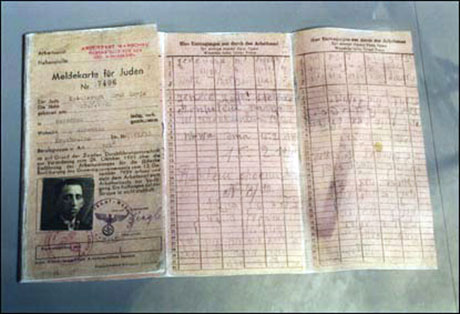

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Loaned by Yael Rosner (Zosia Zajczyk), Jerusalem

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Maggie Tamir, Rehovot

He wrote in Polish and Yiddish, on the work permit he had used in the ghetto prior to its destruction.In the letter he wrote: “I am still alive. I don’t know if I will be tomorrow. I write at a time when there are no longer any Jews in Warsaw. I would like to see my beloved wife and my two beloved children…. These are terrible days for me. I want to live, I feel the end coming.On the second half of the page, he wrote these words in Yiddish: “If anyone should find what I have written, publish it in a newspaper, so that my relatives - who may have survived - will know that at this time I was still alive”.The work permit was found among the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1965.Kalezyk’s fate is unknown.

In Warsaw, Poland, the Nazis established the largest ghetto in all of Europe. 375,000 Jews lived in Warsaw before the war – about 30% of the city’s total population. Immediately after Poland’s surrender in September 1939, the Jews of Warsaw were brutally preyed upon and taken for forced labor. In 1939 the first anti-Jewish decrees were issued. The Jews were forced to wear a white armband with a blue Star of David and economic measures against them were taken that led to the unemployment of most of the city’s Jews. A Judenrat (Jewish council) was established under the leadership of Adam Czerniakow, and in October 1940 the establishment of a ghetto was announced. On November 16 the Jews were forced inside the area of the ghetto. Although a third of the city’s population was Jewish, the ghetto stood on just 2.4% of the city’s surface area. Masses of refugees who had been transported to Warsaw brought the ghetto population up to 450,000.

Surrounded by walls that they built with their own hands and under strict and violent guard, the Jews of Warsaw were cut off from the outside world. Within the ghetto their lives oscillated in the desperate struggle between survival and death from disease or starvation. The living conditions were unbearable, and the ghetto was extremely overcrowded. On average, between six to seven people lived in one room and the daily food rations were the equivalent of one-tenth of the required minimum daily calorie intake. Economic activity in the ghetto was minimal and generally illegal, smuggling of food being the most prevalent of such activity. Those individuals who were active in these illegal acts or had other savings were generally able to survive longer in the ghetto.

The walls of the ghetto could not silence the cultural activity of its inhabitants, however, and despite the appalling living conditions in the ghetto, artists and intellectuals continued their creative endeavors. Moreover, the Nazi occupation and deportation to the ghetto served as an impetus for artists to find some form of expression for the destruction visited upon their world. In the ghetto there were underground libraries, an underground archive (the “Oneg Shabbat” Archive), youth movements and even a symphony orchestra. Books, study, music and theater served as an escape from the harsh reality surrounding them and as a reminder of their previous lives.

The crowded ghetto became a focal point of epidemics and mass mortality, which the Jewish community institutions, foremost the Judenrat and the welfare organizations, were helpless to combat. More than 80,000 Jews died in the ghetto. In July 1942 the deportations to the Treblinka death camp began. When the first deportation orders were received, Adam Czerniakow, the chairman of the Judenrat, refused to prepare the lists of persons slated for deportation, and, instead, committed suicide on July 23, 1942.