Read More...

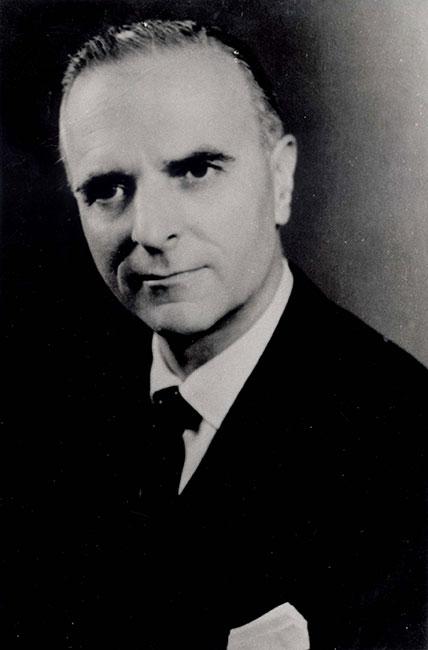

Oskar Schindler, a German Righteous Among the Nations. His status and close relationship with the occupying authorities helped him to save hundreds of Jews by employing them in factories he ran.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4613/822

Yad Vashem Photo Archives

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 4613/412

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 4613/823

In August 1942, Marie-Rose distributed a pastoral letter written by the Bishop Pierre Marie Théas, opposing the arrest of Jews and their deportation. Marie-Rose brought the letter to churches in the Tarn region, riding on her bicycle. She also participated in the rescue of Jewish children and women who were hidden in local monasteries. She rode between these monasteries bringing forged documents and food coupons. Marie-Rose Gineste was later recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations.

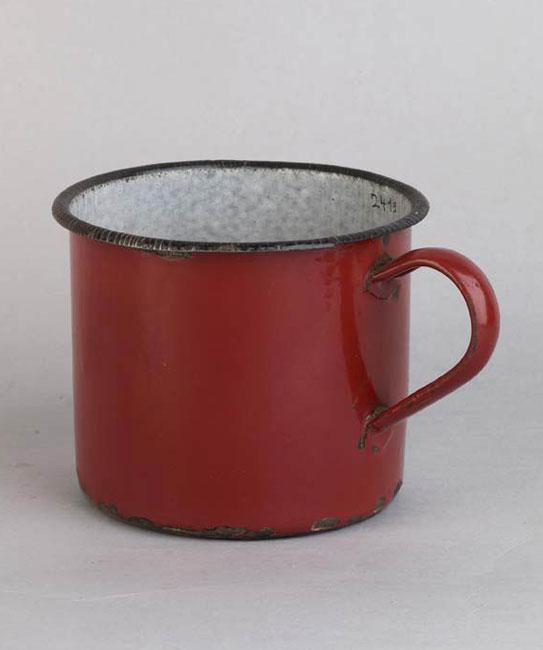

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Marie-Rose Gineste, France

Lassen ferried the Jews in his boat to a ship waiting about 200 meters from the shore, which took them to Sweden.

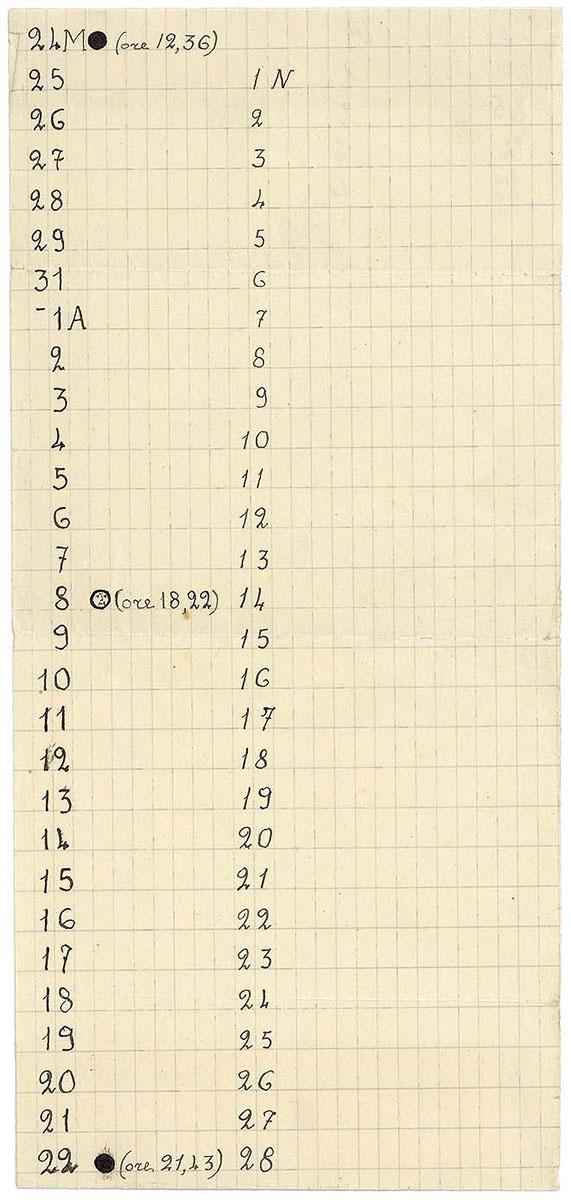

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Donated by Richard Oestermann, Jerusalem

The Artifacts Collection - Yad Vashem

Dr. Adelaide Hautval was forced to wear such a tag when she was deported to Auschwitz

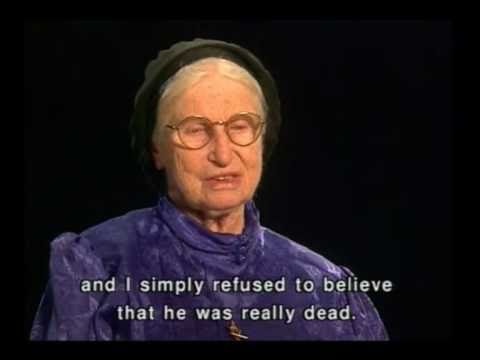

I believe that it was really due to Lorenzo that I am alive today; and not so much for his material aid, as for his having constantly reminded me by his presence… that there still existed a just world outside our own, something and someone still pure and whole… for which it was worth surviving."

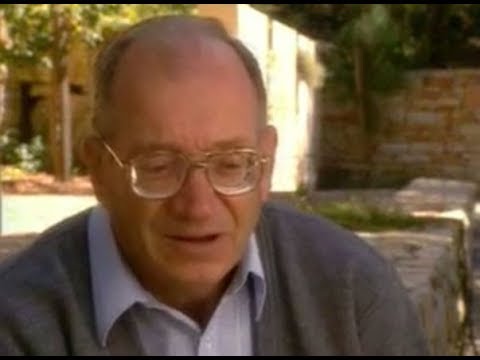

Primo Levi describes his rescuer, Lorenzo Perrone, Righteous Among the Nations

Attitudes towards the Jews during the Holocaust largely ranged from indifference to hostility. The mainstream watched as their former neighbors were rounded up and killed; some collaborated with the perpetrators; many benefited from the expropriation of the Jews’ property. But in this world of moral collapse there was a small minority who mustered extraordinary courage to uphold human values. They were the Righteous Among the Nations.

Often it was a gradual process, with the rescuers becoming increasingly involved in helping the persecuted Jews. Agreeing to hide someone during a raid or round-up - to provide shelter for a day or two until something else could be found – would evolve into a rescue that lasted months and years.

The price that rescuers had to pay for their action differed from one country to another. In Eastern Europe, the Germans executed not only the people who sheltered Jews, but their entire family as well. Notices warning the population against helping the Jews were posted everywhere. In general, punishment was less severe in Western Europe, although there too the consequences could be formidable and some of the Righteous Among the Nations were incarcerated in camps and murdered. Moreover, seeing the brutal treatment of the Jews and the determination on the part of the perpetrators to hunt down every single Jew, people must have feared that they would suffer greatly if they attempted to help the persecuted. In consequence, rescuers and rescued lived under constant fear of being caught; there was always the danger of denunciation by neighbors or collaborators.

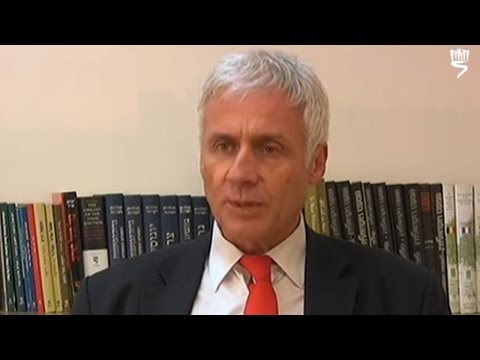

To date (2017), Yad Vashem has recognized 26,513 Righteous from 51 countries and nationalities; there are Christians from all denominations and churches, Muslims and agnostics, men and women of all ages. They come from all walks of life: highly educated people as well as illiterate peasants; public figures as well as people from the margins of society; city dwellers and farmers from the remotest corners of Europe; university professors, teachers, physicians, clergy, nuns, diplomats, simple workers, servants, resistance fighters, policemen, peasants, fishermen, a zoo director, a circus owner, and many more.

The main forms of help extended by the Righteous Among the Nations:

Hiding Jews in the rescuers' home or on their property

In the rural areas in Eastern Europe hideouts or bunkers, as they were called, were dug under houses, cowsheds and barns, where the Jews would be concealed from sight. In addition to the threat of death that hung over the Jews' heads, physical conditions in such dark, cold, airless and crowded places over long periods of time were very hard to bear. The rescuers, whose life was terrorized too, would undertake to provide food – not an easy feat for poor families in wartime – and taking care of all their wards' needs. Jews were also hidden in attics, hideouts in the forest, and in any place that could provide shelter and concealment, such as cemeteries, sewers, animal cages in a zoo, etc. Sometimes the hiding Jews were presented as non-Jews, as relatives or adopted children. Jews were also hidden in apartments in cities, and children were placed in convents with the nuns concealing their true identity. In Western Europe Jews were mostly hidden in houses, farms or convents.

Providing false papers and false identities

In order for Jews to assume the identity of non-Jews they needed false papers and assistance in establishing an existence under an assumed identity. Rescuers in this case would be forgers or officials who produced false documents, clergy who faked baptism certificates, and some foreign diplomats who issued visas or passports contrary to their country's instructions and policy. Diplomats in Budapest in late 1944 issued protective papers and hung their countries flags over whole buildings, so as to put Jews under their country's diplomatic immunity. Some German rescuers, like Oskar Schindler, used pretexts to protect their workers from deportation, claiming the army required the Jews for the war effort.

Smuggling and assisting Jews to escape

Some rescuers helped Jews to leave especially dangerous areas in order to escape to a less dangerous location. They smuggled Jews out of ghettos and prisons and helped them cross borders into unoccupied countries or into areas where the persecution was less intense, such as neutral Switzerland, Italian-controlled regions where there were no deportations, and Hungary before the German occupation in March 1944.