In 1956, while living in Paris, Elie Wiesel wrote an 800 page memoir in Yiddish about his experiences during the Holocaust entitled Un di Velt Hot Geshvign (And the World Remained Silent). The memoir was shortened and translated into French and in 1960 the English version entitled Night was first published. Translated into over 30 languages, this haunting narrative has enabled millions around the world to confront the tragedy, the horror and the pain of the Holocaust.

For those who would like to learn more, Yad Vashem offers these related online resources that provide additional historical context and background (see below).

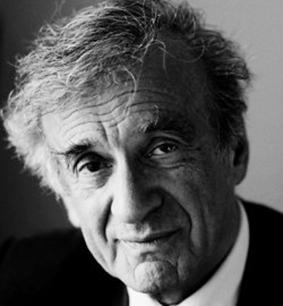

"Whoever listens to a witness, becomes a witness."

Elie Wiesel

Elie Wiesel’s remarks at the closing session of the International Conference “The Legacy of Holocaust Survivors” at Yad Vashem’s Valley of the Communities, April 2002.

"In years to come, visitors will enter this “Emek HaBacha” [Valley of Tears], the Yad Vashem Valley of Communities, to remember what our people lost during the cruelest of our tragedies, and they will weep in the same way as pious and learned Jews weep over the destruction of our Temple long ago. But then they will emerge and see the splendor and majesty of Jerusalem and they will smile, thinking, “Look at these visible and tangible memories we have kept alive just as they have kept our dream and ourselves alive…” Just behind me there is Buczacz. Buczacz – the place where Shai Agnon was born. Shai Agnon said a marvelous thing in Stockholm when he received the Nobel Prize. He said, “Majesty, like all Jews I was born in Jerusalem, but then the Romans came and moved my cradle to Buczacz.” … There are many museums in the world, but the source is here. I have worked in at least one museum, if not two, for many, many years, and nevertheless, in the city of Jerusalem, I must tell the truth: This is the heart and soul of Jewish memory.

What does one do with memory? Here we utter words that we cannot use anywhere else, just as there are certain prayers that you cannot intone anywhere else, only in Jerusalem. Look at the stones. They are testimonies, as are our lives. However, Paul Célan, who lived in Paris and committed suicide, asked: “Who will bear witness for the witness?” He was not the only one. There were other writers who committed suicide – writers in particular, because they felt their words to be paltry. Writers have nothing but words, and they realize that there are no words for this tragedy. There are stones and there are people who come to be in these stones. The despair of the writers who committed suicide must serve as a warning that remains a pitiful part of our legacy. This, good and dear friends, scholars, teachers, historians, researchers, is what you have tried to do for the last three days. You have come together at a very important conference and found the way to delve deeper and deeper into the dimensions of hitherto unexplored memory. You have done so with intelligence and passion, and its impact, the impact of the conference will be felt in many years and decades to come. In this unique place of memory, where the uniqueness of the Jewish tragedy is being preserved, we must therefore be truthful to ourselves and ask, “Will this be the last gathering?”… There is no “last” for us. As long as there will be one survivor, it won’t be the last.

But who will be the last survivor, the last to tell the tale, the one who, like the prophet Jeremiah, said, “I am he, I was there.” Who will be our witness? What will happen to our legacy?...

To some of us, this date [the last day of the conference], April 11, 2002, is very special. April 11, 1945 was the liberation of Buchenwald… I remember that day – it’s our birthday, we say. I remember that we were Jewish adolescents, all orphans, and we did not know what to do with our newly given freedom. Some of us formed a minyan and we recited kaddish, our first kaddish as free Jews. I think I thought that this kaddish would never end; it would last until we died, and in a way I was right.

This kaddish is still within us, and I sometimes wonder whether, in all my writings, I am doing anything else, or just saying kaddish.

Often we feel weary and melancholy and close to despair, not only for the past, but also for the present. In other words, for what was done by so many on so many levels to the memory of our past. I am not referring to the professional Holocaust deniers. They don’t deserve the dignity of a debate. I refer to a Nobel Prize winner in literature, Saramago, who came here, who had the arrogance to come to tell Palestinians that what Israel is doing to them is what Germans have done to the Jews. Writers should first read before they write. But I also refer to all those who use their skill, movie-makers and all people from all fields who trivialize our tragedy. The authenticity of the tragedy is being lost to some of them.

But all of them together belong to a minority. In general terms, we may judge the situation as relatively positive. Never before have there been so many events, so many academic conferences, so many chairs, or so many books on the Holocaust. Its place in history can no longer be questioned. Can it be distorted? It can; but as long as Yad Vashem …and [its] archives are open to interested scholars and students ad bo hamashiach [until the Messiah comes], which means forever, there will always be voices to correct innocent errors and deliberate misjudgments. They will be our heirs, our witnesses. They will be the custodians of our memories, thus of our legacy. For whoever listens to a witness becomes a witness.

So what will our legacy be? First, let us perhaps see what it has been for survivors. It was an attempt to remain human even in inhuman conditions. Even inside Auschwitz, these men and women were capable of courage, generosity, and compassion; a piece of bread, a good word, a prayer on Shabbat; or a smile. All those were enough to give strength to a fellow prisoner. After the war, these survivors could have chosen nihilism, hedonism, violent revenge, or just extreme selfishness. They could have said to the world, “We owe you nothing. We paid the price. We want to enjoy life now and to hell with you.” They could have said that. Instead, however, they chose to emphasize hope and dignity… Many survivors came to Israel where, on the ruins of so many lives, they built a new state that celebrates dignity, honor, and humanity, in spite of everything people say about Israel and the people of Israel.

Our legacy is rooted in what we call ahavat yisrael – the love of Israel: Israel the State and Israel the People. No one loves Israel as a survivor does. No one. The legacy is that whatever happens to and in Jerusalem affects all Jews, wherever they may dwell, whether they live in fear or prosperity. When one community is threatened, all of our people, the entire people, must muster its energies to rush to its aid. When one segment is slandered and one person is humiliated, we must all raise our voices in protest. From our experience, we have learned that no Jew must ever feel alone and abandoned. A lone Jew is exposed to doubt and danger. Together, we know how to resist perils – above all, the peril of indifference. A Jew must never be indifferent to other Jews. We must never remain silent when Israel needs our voice.

However, we must not be indifferent to other people’s suffering, either. That, too, is part of our moral legacy. When people suffer from injustice, when they are victims of society or victims of destiny, we must not check their identity cards, but offer them our compassion. In other words, we must do for others what no one has done for us: give food to the hungry, a home to the homeless, help to the helpless, and hope to the hopeless.

We, who were forgotten by Creation and perhaps abandoned by its Creator, must demonstrate our faith in both. That faith preceded us and will follow us in history. We, who inside the barracks and the darkness saw all those paths leading to death, witnessed all those endeavors dictated by the enemy, and were dominated by death, still proclaim our belief in the Jewish tradition with every fiber of our being: Everything about life is in life, however frail and vulnerable it may be. Ultimately, therefore, the question we had to face after liberation was, “What does one do with one’s memories and one’s suffering?” We could have used them as weapons to inflict suffering on others, but we did not. Isn’t Israel a great triumph, if not the greatest achieved by our generation?….

Today there is still fear in this land, sanctified by its eternal quest for peace. That, too, is part of our legacy. Maimonides wants us to play for peace among all nations. Even when they fight among themselves, we somehow happen to become their victims. Thus, we tell the world today and generations to come to learn from us, the last remnant of the bloodiest tragedy in recorded history. The memory of suffering and agony can and must be invoked so as to prevent further suffering and more agony. Faced with the memory of the moral blankness of the enemy, it is incumbent upon us to show greater sensitivity to ethical issues and challenges, and tell those who believe in death that that is not the way to fight for their cause. I cannot begin to tell you, my good friends here, how perturbed I am, how worried I am, how dismayed I am that the world does not realized the danger of suicide bombings. I call them “suicide killers.” I cannot understand that. These are people who have made death into a cult, death into a passion, death into a theology. They believe that they kill in the name of their god, and in doing so they don’t realize that they make their god into a killer. And the world refuses to understand that. And the world doesn’t realize that we have learned in history that whatever happens to us is usually a beginning…. Something is wrong with the world again, which means we have a legacy they have not learned from yet. There is a midrash that the prophet Elijah actually goes around the world with a bag and collects tales of Jewish suffering. And when the Messiah comes, the stories of that bag will become the new Torah from which God Himself will learn and teach. I am sure that one place that He will visit day and night is this place."