Despite infinite risks and prohibitions, Jewish belief and practice persisted during the Holocaust, the dialogue with the Creator of the Universe never ceasing. Jewish observance was expressed in a myriad of ways—reflecting a variety of attitudes and approaches—and was tailored to meet the conditions imposed upon the Jews during that period. “Even in that inferno,” wrote Israeli author Aaron Appelfeld, “those of perfect faith remained steadfast in the beliefs of their ancestors.”

Likened with these true believers are those artists who continued to create despite, and at times in response to, the inherent dangers and adverse conditions they encountered during the Holocaust. Both the pious and the artists adhered to their faith—in God or creativity—throughout the hardest to fathom of circumstances. By immersing themselves in the spiritual realm, they strove to rise above the horrors of their circumstances, and withstand—both physically and mentally—the destruction of flesh and spirit.

Brethren in misery and endurance, it is little wonder the works of Holocaust artists frequently depict the religiously devout and their practices in the ghettos and camps. The Yad Vashem Art Collection contains many such Holocaust-era works. These unique renderings of prayer and festival rituals testify to the fortitude of both Holocaust artists and true believers, simultaneously corroborating the many survivor accounts pertaining to religious observance.

Graphic artist Pesach Irsai was typical of these artists. In July 1944, Irsai arrived at the “Hungarian sub-camp” in Bergen-Belsen—one of 1,684 Hungarian Jews brought in a special convoy that was destined to be freed by the SS as a sign of goodwill pertaining to negotiations between Zionist leader Rezso (Israel) Kasztner and Adolf Eichmann. Some of these Jews spent about five months at Bergen-Belsen and celebrated the High Holidays there: “On Rosh Hashanah [the Jewish New Year] the kitchen workers managed to get a shofar [ram’s horn],” recalled Riva Abramowitz in her testimony given at Yad Vashem. “The Stamar Rebbe decided to blow the shofar in the courtyard, despite the strict prohibition against convening there… People crowded up against the fence. They didn’t know where the sound of the shofar was coming from.”

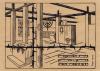

Realizing the courtyard could not be used habitually as a place of worship, the detainees—many of whom were observant—erected a makeshift synagogue at the far end of the men’s infirmary barrack. Irsai’s print shows the well-appointed synagogue, with the Holy Ark, a cantor’s lectern, and various ornaments, including a seven-branched candelabrum, the Tablets of the Covenant, and a Star of David. Irsai, well aware of the capacity of art to beautify stark reality, leaves no room for error as to the location of the synagogue. The barbed wire that divides the sketch into four quadrants is not a decorative element; it is a clear illustration of reality in the camp—a place where Jews preserved their tradition even behind barbed wire.

Following the arrival of the first deportees to the Theresienstadt ghetto in Czechoslovakia in late November 1941, extensive artistic activity began to take place there. Among the deportees were several artists who were consigned into a department instructed to provide ghetto authorities with plans, drawings and graphs favorably depicting ghetto life. These illustrations were commissioned to enable the Nazis to conceal the reality of deprivation and annihilation rampant in the camp. While most of these artists’ works were created at the orders of the Nazi commanders, others were done in secret defiance—attesting to the reality of the prisoners’ conditions and their adherence to Jewish tradition.

“When we reached Theresienstadt, we were astonished to see that on the one hand work continued on the Sabbath and Jewish holidays, and on the other hand no restrictions were placed on holding prayer services,” testified former ghetto residents. According to other survivor reports, services were held in several places in the ghetto (i.e. attics or basements), with each community congregating around a rabbi from its native district. In some of the makeshift synagogues services were quite lively, and during the holidays most were packed.

Artist Ferdinand (Felix) Bloch captures the observance of the Sukkot holiday (according to one testimony) in his illustration Prayer. The Torah scroll is carried by one of the congregants, with the cantor and rabbi standing on either side of the pulpit adorned with prayer shawls and wearing hats typical to German Jewry cantors and rabbis. Everything is sheathed in attic fog. Only the ark and the Torah scroll bask in light—the light of faith that strengthens those who take refuge in its rays.

An austere drawing by artist Jan Burka illustrates a weekday service in a similar attic that has been converted into a prayer house. Burka was sent to Theresienstadt in 1942, at the age of 18. Although he was not observant, he was drawn to documenting the observance of Jewish rituals in the ghetto.

In Theresienstadt, religiously observant Jews were also permitted—in most instances—to lay tefillin (phylacteries). This integral rite linking Jews to the traditions of their ancestors is illustrated in the sketch Praying with Tefillin by Otto Unger. “All my thoughts were focused on my tefillin,” notes Rabbi Ehrlich in his memoirs. “The tefillin were all I had left and through them I could serve the Holy One Blessed Be He.”

Theresienstadt artist Asher (Arthur) Berlinger created a small, intimate drawing illustrating the determination of those of perfect faith. These devout carried in their hearts and etched on their synagogue walls the words of the prophet Malachi, who promises redemption to the observant: “Remember the teachings of my servant Moses” (Malachi 3:22). In the adornment on the upper part of the pulpit “Terezin 1940” is inscribed, indicating not only the location of the prayer house, but that the redemption that was so desperately sought after did not arrive for many who were deported from Theresienstadt to the death camps.

Despite their spiritual devotion, Holocaust artists and the religiously observant suffered the same fate, their affinity not outweighing the circumstance of the time. Alas, in the bleakest hour of Shoah, “the stars of heaven and the constellations thereof [did] not give their light” (Isaiah 13:10) even to the truest artists and those of perfect faith.

First published in Yad Vashem Jerusalem magazine, #28, October 2002