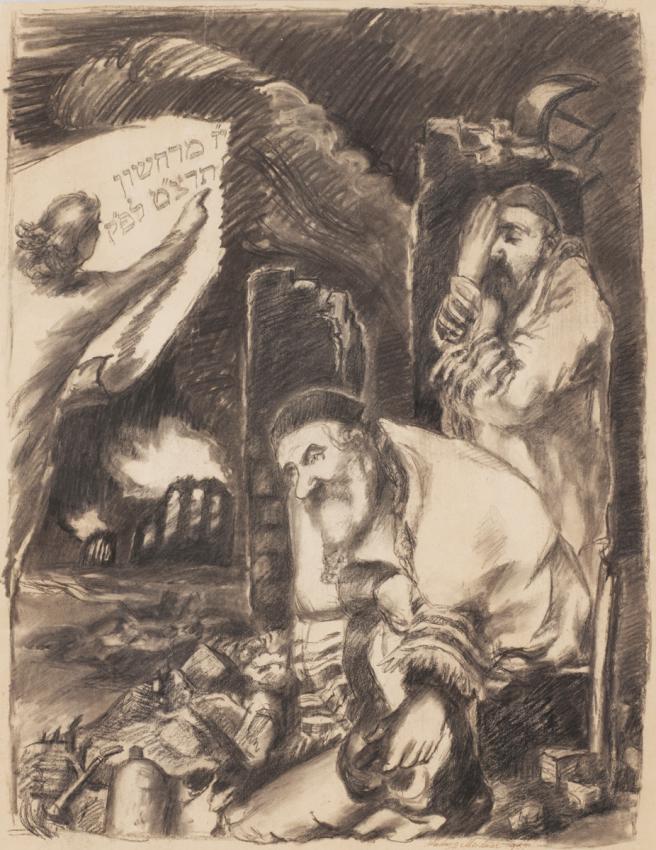

Ludwig Meidner (1884-1966), In Memory of our Destroyed Synagogues in Germany 10/11/1938, 1939

Yad Vashem Art Collection

“This Judaism again I have come to accept with all my spiritual powers; to this treasure, which the most modern people neither know nor respect, belongs my innermost being."

Ludwig Meidner, 1930

The rise of the Nazis to power in 1933 sealed the fate of avant-garde artists: their art works were declared "degenerate" by the newly instilled ideology as a defiling influence on the Aryan race, not least because this Art was viewed as having had Jewish characteristics.

An exhibition under this very title was opened in Munich in 1937, aiming to incite German citizens against avant-garde art. Among the works presented at the infamous exhibition were the paintings of Ludwig Meidner, a Jewish artist expelled from all public artistic presence alongside his fellow modernists, when German art and culture underwent increasing Nazification under Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. Meidner's books and monographs were thrown into the flames at mass book burnings, and 84 of his art works were taken off display at a number of museums across Germany.

On the artist's 50th birthday, in 1934, a solo exhibition of his works was presented at the Jewish museum in Berlin: his last exhibition until the fall of the Nazi regime. Shortly afterwards, Meidner, once a preeminent master at the Levin-Fonka Art Studio in Berlin who raised such illustrious students as Felix Nussbaum and Felka Platek, found himself struggling to make ends meet. Distraught, he accepted an invitation to teach art at the Yavne Realgymnasium in Cologne, where he moved in 1935 with his painter wife Else (née Maier) and their son David.

Paradoxically, as the persecution of Jews intensified, Meidner became increasingly observant, moving from the Conservative branch of Judaism towards Orthodoxy. It was as an Orthodox Jew that he experienced the events of November 1938 in Cologne that later became known as Kristallnacht (it was called by the Jews "the November pogrom") and took to signing his artworks with the Hebrew letter "Mem" from that time onwards.

In his 1939 drawing in chalk and charcoal – a far departure from the style of his more familiar expressionist works – Meidner reacts to the destruction surrounding him. In an inscription on the back of the work, he unequivocally dedicates it to "the memory of our destroyed synagogues in Germany." The drawing portrays two bearded figures, each donning a skullcap and wrapped in a prayer shawl, against the backdrop of burning ruins and billowing smoke. The front figure, sitting according to the traditional Jewish mourning custom, is holding up a parchment of a desecrated Torah scroll. The man behind him is covering half of his face with his hand, eyes shut in an expression of deep distress, evoking Shema Yisrael – the foundational Jewish prayer. These two figures thus symbolize the Jewish People’s attachment to their legacy in spite of past and present tribulations. For Meidner, the Torah and the Jewish faith are the very source of strength for the Jewish people at this fateful hour.

The exact date of the pogrom according to the Jewish calendar is indicated upon a parchment fragment echoing with the torn Torah scroll: "17 MarHeshvan 5699." An enigmatic figure only seen from the back – a woman, or perhaps an angel – is pointing a finger at the inscription, in an iconographic reference to Rembrandt's "Feast of Balthazar." In that famous painting, depicting an episode from the Book of Daniel, amidst a royal feast prominently displaying the vessels plundered from the Temple in Jerusalem, a mysterious hand appeared and inscribed a riddle phrase upon the wall, later deciphered by the Prophet Daniel as a prediction of the imminent fall of the mighty Babylonian Empire. Thus, Meidner draws a common thread between the destruction of the Temple and the devastating events of Kristallnacht. The artist both foresees and hopes that the destruction and profanation of Jewish synagogues in Germany will bring about the end of the Third Reich. Both the style and the content of the artwork herald the beginning of an artistic series dedicated to the sufferings of the Jews of Poland from 1942-1945, whilst he and his family found refuge in England, managing a narrow escape just months after the events described in the powerful drawing.

First published in Yad Vashem Jerusalem magazine, #72, January 2014