The fate of artist Felix Nussbaum family, from Osnabrueck, Germany, substantiates the desperate efforts to find shelter and refuge on foreign soil. It is the history of one family among many that found itself in the maelstrom of hopeless flight.

Philip Nussbaum, Felix’s father, was a proud German patriot who belonged to the organization of World War I veterans. When the new regime came to power, he had to surrender his membership. In his parting remarks, he said, “... for the last time, dear comrades-in-arms, I salute you as a loyal soldier... And if again I am called to the flag, I am ready and willing.”

At that time, his son, the artist Felix, was in Rome with a small group of German students at an extension of the Berlin Academy of the Arts, after winning a prestigious scholarship. In April 1933, Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda, visited the artistic elite and lectured them on the Fuhrer’s artistic doctrine. “The Aryan race and heroism are the main themes that the Nazi artist is to develop.” Felix understood that there was no place for him, as an artist and a Jew, within the confines of this doctrine. He left Rome by early May and his scholarship was revoked a short time later. In his work, The Great Disaster, 1939, he expressed his intuition concerning the dramatic change that Hitler’s accession had wrought—the destruction of Europe and of Western civilization.

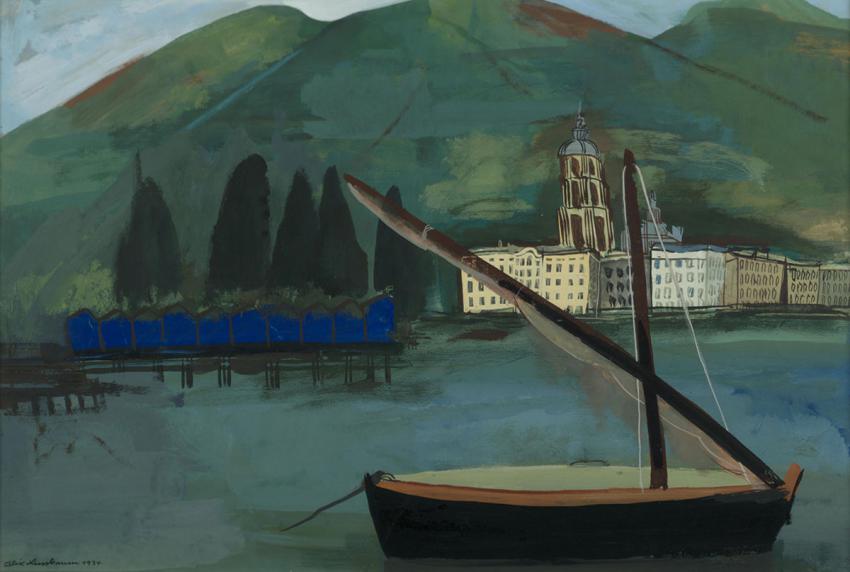

Felix’s parents, Philip and Rachel, left Osnabrueck, as did many Jewish inhabitants of this town. His older brother, Justus, and his family remained to run the family’s thriving metal business. After a brief stay in Switzerland, Felix’s parents traveled south to meet with their beloved son in Rapallo, a fishing town on the Italian Riviera. The sunshine and the ambiance of the place eclipsed the clouds of war, and the Nussbaums spent the summer of 1934 together, in what would be Felix’s last encounter with his parents. His uplifted mood is expressed in the joyous, carefree colors of his works during this time, e.g., The Beach at Rapallo, 1934.

In 1935, his parents succumbed to their nostalgia for Germany and expressed their wish to return to their homeland, despite the fierce objections of their son, Felix, who rewrote the last line in his father’s parting poem: “... And if again I am called to the flag, I will desert to a faraway place for sure.” It was the only time he objected to the views of his father, his source of spiritual and economic support.

The family members parted ways. Felix and his life partner, Felka Platek decided not to return to Germany. They first went to Paris in January 1935 and then to the Belgian resort town of Ostende. Several months later, they moved in with friends in Brussels. There, in October 1937, they married. Felix’s brother Justus, was forced to emigrate in 1937 when all Jewish businesses in Osnabrueck were Aryanized. Justus, his wife, and their two-year-old daughter Marianne fled to the Netherlands on 2 July of that year. There, together with several additional forced migrants, he managed to establish a scrap-metal company.

In the meantime, the situation in Germany was deteriorating. During the Kristallnacht pogrom, the synagogue in Osnabrueck was torched, Jewish homes were looted, and all Jewish men were taken to Dachau. In May 1939, Felix’s parents decided to leave Germany. They fled to Amsterdam to reunite with Justus, their elder son.

When Belgium and the Netherlands were occupied in May 1940, Felix was arrested in his apartment and, like all other aliens, taken to the Saint Cyprien camp in southern France. His interment there was a personal watershed; then Felix comprehended the true extent of mortal peril as a Jew under Nazi rule. He expressed this epiphany in his important work, The Camp Synagogue at St. Cyprien, 1941—a unique work that symbolizes Felix’s realization that he belongs to the Jewish people and is so perceived by others. It was his first painting on a Jewish theme in many years.

In August 1940, in despair after three months of suffering under humiliating conditions in Saint Cyprien, Felix applied to return to Germany. When he reached the checkpoint at Bordeaux, he decided to escape by boarding a passenger train to Brussels, where he would be reunited with his beloved wife. From 1940 on, Felix Nussbaum lived in hiding with no source of livelihood. His Belgian friends met his needs and even provided him with a studio and art supplies. Lacking residency papers and in continual danger of being discovered, Felix moved from his hideout apartment to his studio and back, pursuing his artistic endeavors without respite. The themes of concern to him were fear, persecution, and the curse that loomed over the family’s members.

The fate of the expanded Nussbaum family was sealed. In August 1943, the protection given to employees of Justus Nussbaum’s scrap-metal business was revoked. Justus, his wife, their daughter Marianne, and the Nussbaum parents were arrested in their hideout apartments and sent to the Westerbork. Half a year later, on 8 February 1944, Philip and Rachel Nussbaum, the artist’s parents, were deported from Westerbork to Auschwitz.

On 20 July 1944, Felix and Felka were arrested in their hideout and sent to Mechelen camp. Later that month they were deported to Auschwitz, where Felix Nussbaum was murdered on 9 August. His older brother, Justus Nussbaum, was transported from Westerbork to Auschwitz on 3 September. Three days later, Herta, Felix’s sister-in-law, and Marianne, his niece, were murdered in Auschwitz. In late October 1944, Justus was sent to the Stutthof camp, where he died of exhaustion some two months later.

This chronology manifests the extirpation of one family that, despite years of flight, could not escape the long talons of the Nazi beast. Europe had become enemy territory. Nussbaum expressed the motif of dead end in an early work, European Vision—The Refugee, 1939. The Jewish refugee, holding his head in his hands, finds no shelter on the threatening globe, which stands on the table. The entrance to the room, wide open, provides no source of hope either. Symbols of extinction—a tree shedding its leaves and ravens hovering over a corpse—lurk outside. As if the artist already knew the final outcome, that no member of his family would survive the inferno. Felix endured for almost a full decade, against all odds, but he, too, was murdered a month before the liberation of Brussels. However, his works continue to tell his story, that of his family, and that of the fate of the Jewish people.

First published in Yad Vashem Jerusalem magazine, #18, April 2000