Over the course of eight months, from May to December 1943, Max Plaček – a prisoner in Terezin – drew over 500 portraits of artists, scientists, intellectuals and cultural figures that testify to the human richness of the ghetto’s population. The artist sketched his final portrait a week before he was transported to Auschwitz. In 1944, he was sent to Sachsenhausen, where he was murdered.

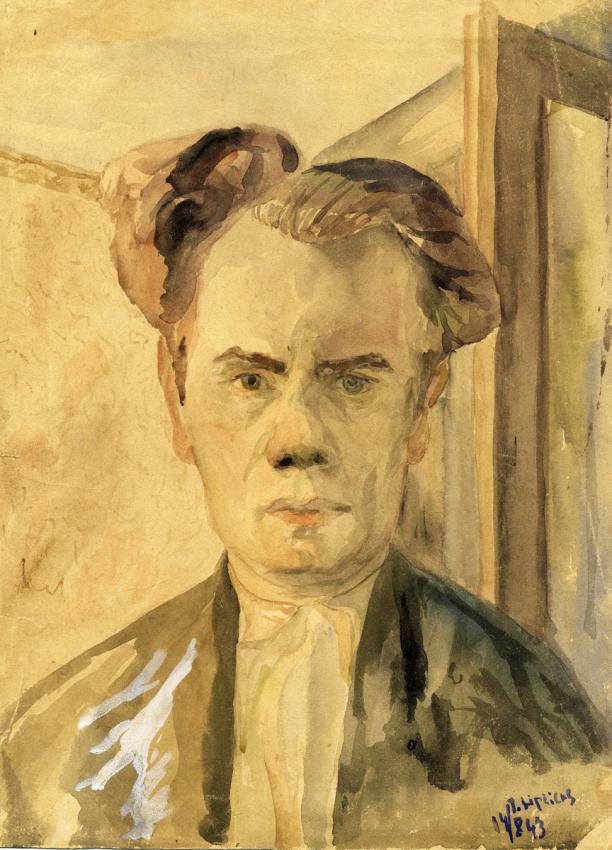

In the Kovno ghetto, painter Jacob Lifschitz undertook documentation efforts together with artists Esther Lurie and Josef Schlesinger. At night, in the attic where he lived with his wife and daughter, Lifschitz drew poignant portraits of his relatives. Just before the liquidation of the ghetto in the summer of 1944, Lifschitz hid over 100 works of art in the nearby cemetery, concealed in ceramic jugs. He was sent to Dachau, and, from there, to forced labor in Kaufering. In the severe conditions of camp, Lifschitz starved to death in 1945. After the war, his wife and daughter returned to the ghetto ruins and found his works in their hiding place. Ultimately, these works – including a self-portrait and many others – were brought to Yad Vashem. Together with Plaček’s last portrait, Lifschitz’s self-portrait were be displayed in a new exhibition marking International Holocaust Remembrance Day entitled: “Last Portrait: Painting for Posterity.”

The exhibition presented almost 200 portraits taken from Yad Vashem’s Art Collection that were drawn by 21 artists of varied origins and backgrounds who labored to preserve images of their friends and loved ones for posterity. Aided by a simple pencil or brush, the artists put to paper or canvas the image of the persecuted, and thus proudly declared their identity and individuality. The works testify to the tremendous creative drive that moved these artists to draw diligently entire series of portraits in the most severe of circumstances. This determination was neither an isolated nor chance event, but a phenomenon that recurred in different places during the Holocaust.

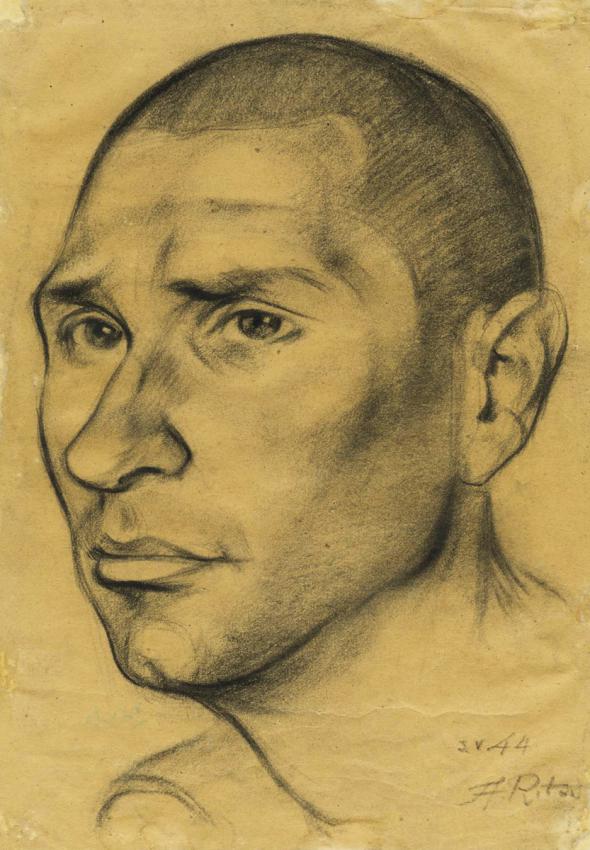

For many of the subjects, the artists’ recording of their faces, moments before death, makes for their final portraits. This was certainly true in the case of Arthur Ritov’s clandestine sketching of 47 of his fellow H.K.P. unit members in the Riga ghetto from 1942 to 1944. In July 1944, following the approach of the Red Army forces, many of those drawn were sent to their deaths in the mine fields. Ritov managed to escape and hide, and survived the war. The drawings, upon which he made sure to record personal details and exact dates, memorialize his friends, and represent a passionate testament to their existence.

Each portrait in the exhibition binds together three stories: the artist’s, the subject's, and that of the work itself. Efforts were therefore made to note, together with the biography of each artist, the special circumstances in which the portraits were created, and how the artist succeeded in procuring art supplies despite the severe shortages of food and other basic necessities. Museum staff used Yad Vashem’s databases, including the Hall of Names and Archives, to retrieve information about the subjects of the portraits. It is hoped that the exhibition will result in more information being discovered regarding the people whose faces look upon us from within the drawings, and that those still anonymous may finally be identified.

For Lifschitz, Plaček, and many more of the artists whose work is displayed in the exhibition, their project to immortalize their companions’ faces on paper also represents the last portrait of their oeuvre. Thanks to these drawings and paintings, we can look at the victims’ faces, learn about their identities, and trace their fate. Our gaze meets the eyes of the children, women and men whose human image is indelible.

“Last Portrait: Painting for Posterity” opened on 23 January 2012 in the Yad Vashem Exhibitions Pavilion.

The exhibition was generously supported by Mrs. Sura Smolas, z"l, France.

First published in Yad Vashem Jerusalem magazine, #64, January 2012