After infiltrating the Vilna ghetto on a precarious rescue mission only days before its final liquidation, Jewish artist and partisan Alexander Bogen was plagued by a reverberating question: “What motivates someone at the precipice of death to engage in artistic creation?”

An artist and a native of Vilna, Bogen neither forsook his artistry nor ceased to sketch the people, places and events he encountered following the Nazi occupation of Lithuania. However, it was only after returning to the ghetto in September 1943 that he began considering the wartime function of innovation: to transform pen into sword, transcend the finite parameters of time and space, and retain a spark of humanity in the face of despair. These artistic objectives crystallized in his mind through encounters with ghetto residents, former friends and colleagues: the fellow-artist who stood by his easel—bedraggled and starving—yet oblivious to his condition having captured the elusive smile of his model on canvas; the all-around genius who wandered through the streets heedless of his personal fate having solved an elaborate mathematics equation; the young orphan abandoned on a street corner with but a doll in her arms, who Bogen could not save, so sketched “out of helplessness, passivity, and the inability to offer up salvation."

Aside from reinforcing his personal devotion to art, Bogen’s mission in the ghetto helped facilitate the successful rescue of members of the United Partisan Organization (FPO)—a Jewish underground movement active in the ghetto. After breaching the ghetto walls armed with a pistol and two hand grenades, Bogen, along with two fellow partisans, reached FPO head Abba Kovner’s headquarters. Bogen presented him with a letter from Fyodor Markov, commander of the partisan division in Belarussia’s Narocz Forest.

“From the beginning, Kovner’s intention had been to launch a full-scale armed revolt in the ghetto to sanctify God’s name and foster pride in the Jews even in their moment of defeat,” recalls Bogen. “It was a noble conception, but not practical in my opinion. We couldn’t fight the Nazis in the narrow alleyways of the ghetto with our few, primitive weapons. We would have zero chance.”

With the end in sight, Kovner did not abandon his plans for revolt, but acceded to the partisans’ request to smuggle ghetto residents (Including members of the FPO) to the forests.

One hundred and fifty Jewish underground members were assembled and divided into five units, which Bogen helped train: “I distributed primitive weapons and copies of my map of the forest. I taught them how to prepare for and fight the enemy, find food, read a compass, where to hide, and where and when to walk—all the tactical information one needs to know to become a partisan,” says Bogen. He assumed command of one unit, which included his wife, Rachel, and his mother-in-law. In the late night hours he helped secure the groups’ escape from the ghetto; a few days later, all five units arrived safely in the forests where they joined the non-Jewish partisan ranks.

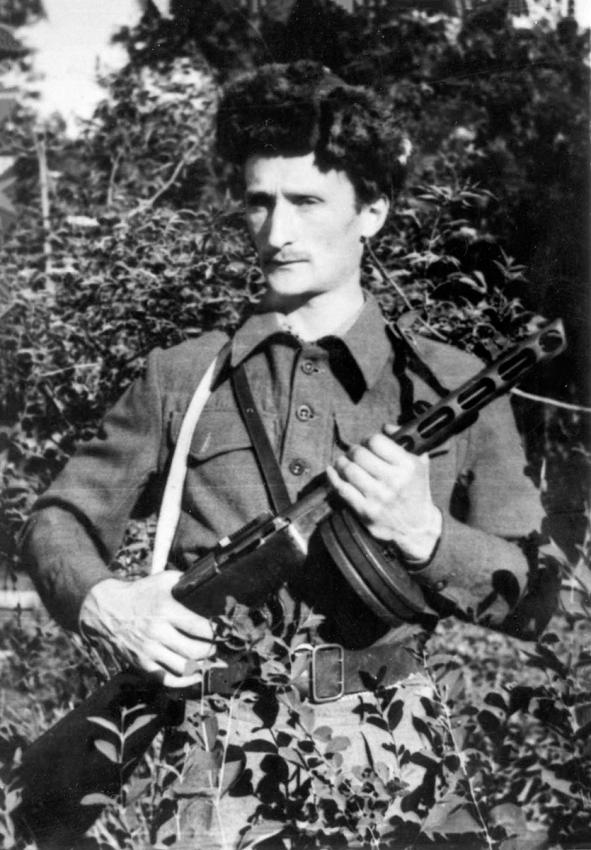

With Markov’s permission, Bogen retained command of his 30-person unit, which became the only all-Jewish partisan brigade—“Nekama (Vengeance).” The unit achieved many successes and was responsible for missions such as mining railroad tracks and derailing trains, sabotaging German weapons banks and food rations that were being sent to the front, and disseminating information about the mass extermination and active resistance in the nearby ghettos, villages, and towns.

Partisan life was stark and grueling. Aside from risky reconnaissance missions and clashes with the enemy, fighters suffered from exposure to the elements, insufficient food and illness. For Jewish partisans the conditions were even more dire; they had to face the residual “tragedy, mental torment, longing and worry about the fate of loved ones left behind in the ghetto,” noted Bogen, as well as antisemitic treatment from non-Jewish partisans. “Jewish partisans—especially those who served in mixed units with Russians, Lituanians and Belarussians—always had to prove they were willing to volunteer first for missions and risk the most,” says Bogen. “They were often sent poorly armed on ‘hopeless’ operations that had little chance of success.”

Even the Nekama Unit became problematic to the Soviet partisan leadership due to its all-Jewish character despite its many achievements. The unit was disbanded after several months and Bogen (after a few other appointments in mixed units) joined a group of historians commissioned to document partisan activities.

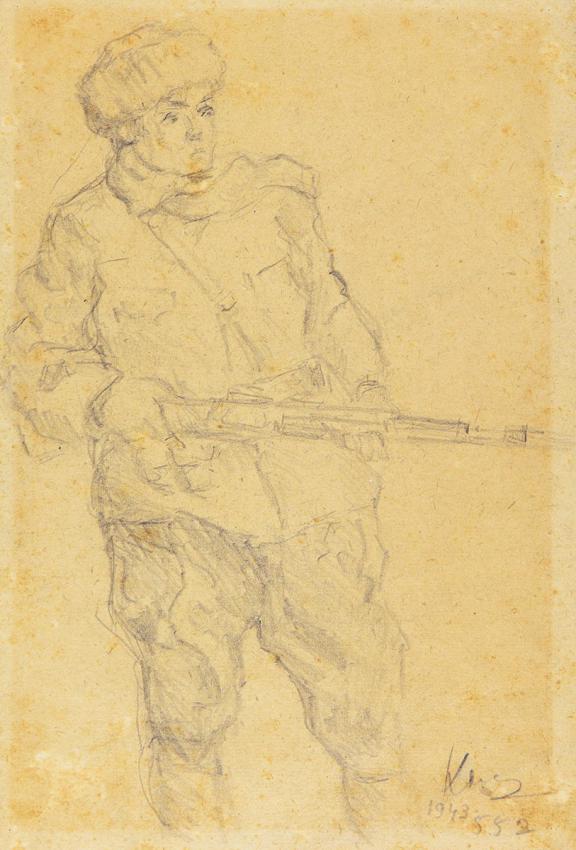

Bogen captured his brothers-in-arms through the medium of art, sketching scenes of partisan battle, rest, ambush, dress, and diversion on random scraps of paper using charcoal made from burnt branches. “I would try to capture the typical situations that we would encounter—a unit returning from its operation… its members sitting around a bonfire, playing cards, drinking Vodka, recounting the tales of what befell them…” recounts Bogen. “In battle, at partisan headquarters… I would pull out my paper and sketch these things as they were happening, as a reaction to the events taking place.”

“Ultimately, when I asked myself why I was drawing, when I was fighting day and night… [I realized that it was] something similar to biological continuity. Every man, every people wishes to leave this one thing… To be creative during the Holocaust was also a protest. Each man when standing face-to-face with cruel danger, with death, reacts in his own way. The artist reacts in an artistic way. This is his weapon… This is what shows that the Germans could not break his spirit.”

Alexander Bogen donated 37 of his works created during his days as a partisan to Yad Vashem. Several of these pieces are exhibited in Yad Vashem’s Holocaust History Museum in the section dedicated to Jewish fighting.

First published in Yad Vashem Jerusalem magazine, #30, April 2003