Born in Mährisch Ostrau, Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1893. Died in St. Louis, United States, in 1980.

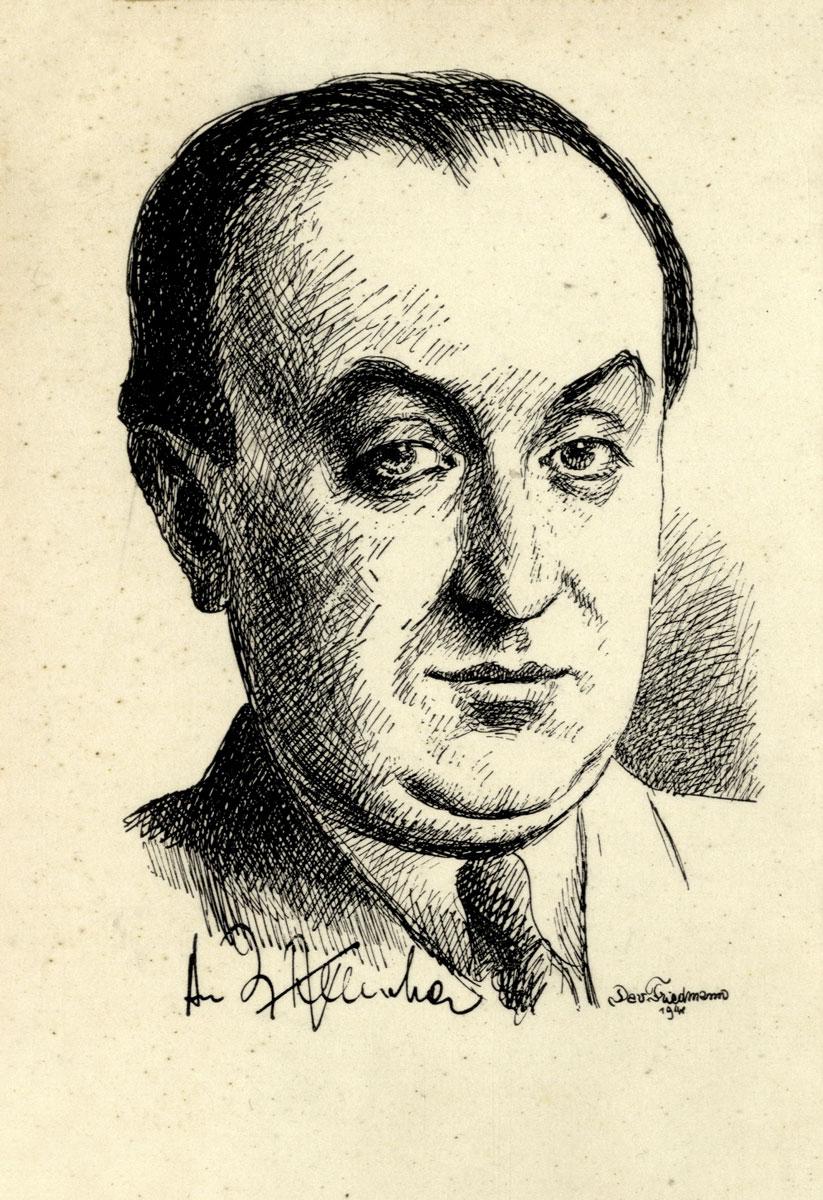

"From the time of my escape from Berlin to Prague, I was trying to get acquainted with the members of its Jewish Community to call their attention to my ability as a portraitist. Once I made it known that I had the intention of putting together an album of portraits, the orders came in abundance.”

David Friedmann, “Das Krafft Quartett”, 8 May 1973 (Testimony), Yad Vashem Collection

Architect, stage and graphic designer. In Theresienstadt, responsible for the stage design and decoration in the Leisure Time Department of the Ältestenrat.

Born 1904 in Kutná Hora, Austro-Hungarian Empire. Active in famous Prague theaters. In 1942-1943, by Nazi order, in charge of arranging in the Prague Jewish Community looted Judaica items for a display. In July 1943, deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. In October 1944, transported to Auschwitz, where he was murdered.

Lithograph

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

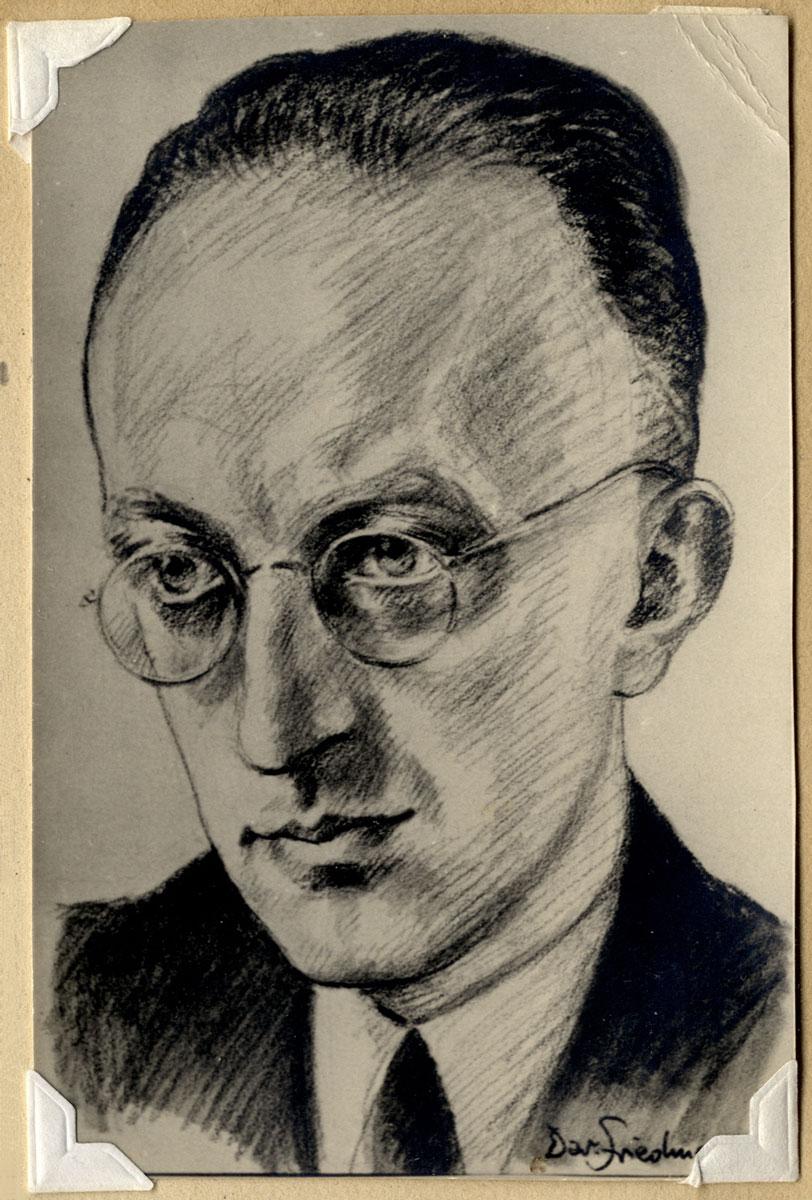

Electrical engineer. Member of the Ältestenrat and Head of the Production Department in Theresienstadt.

Born 1906 in Prague, Austro-Hungarian Empire. Deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto with the Aufbaukommando in December 1941. After the war, lived in Prague, where he died in 1978.

Photograph of drawing

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

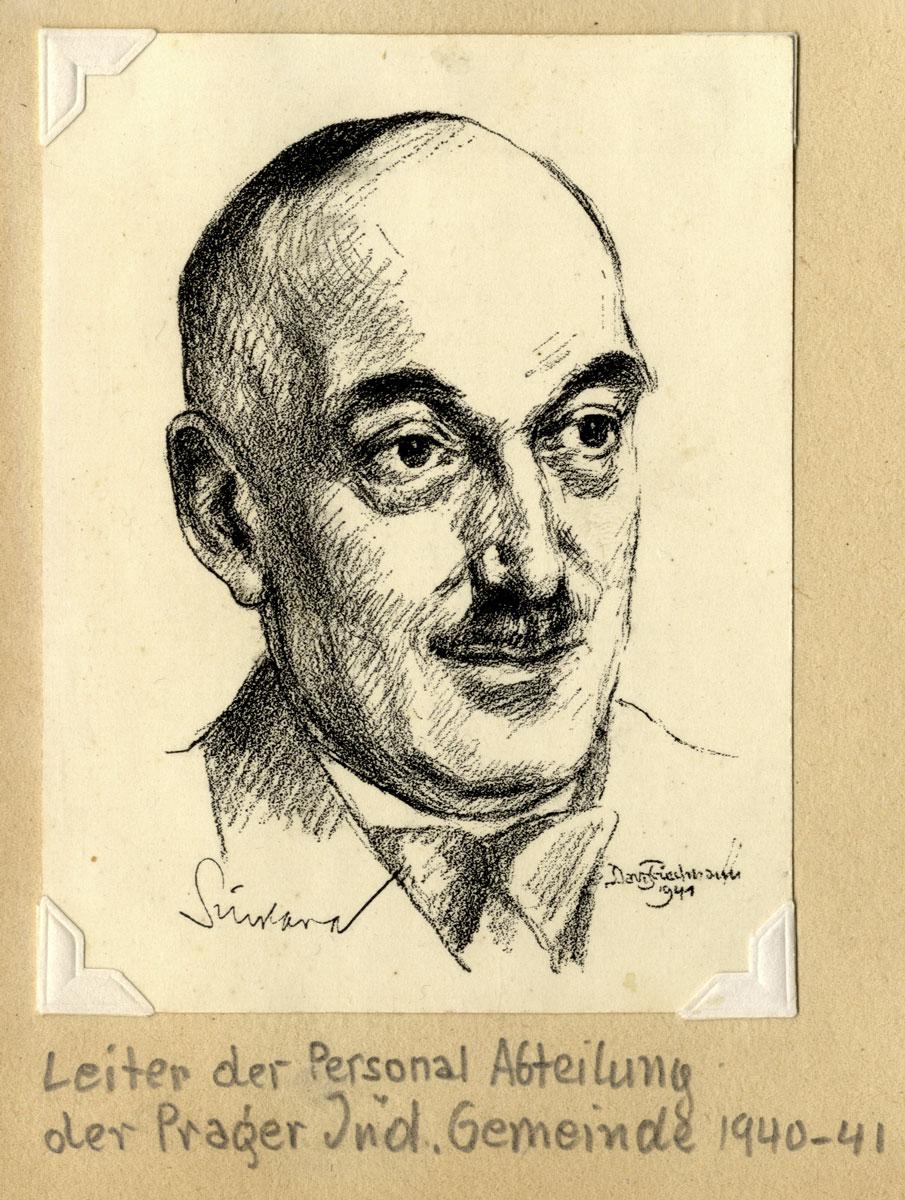

Director of the Personnel Department, Prague Jewish Community.

Born in 1885. In July 1943, deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. In September 1943, transported to Auschwitz, where he was murdered.

Lithograph

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

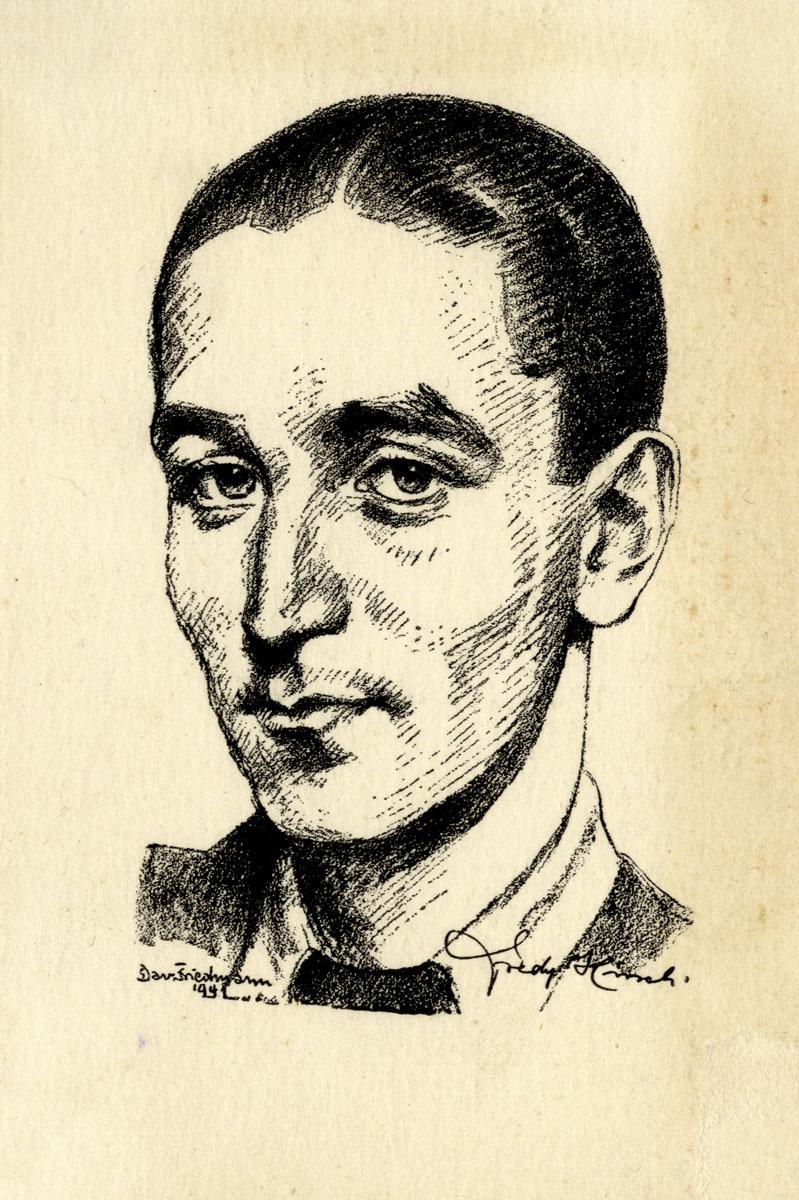

Physical education teacher, youth leader in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Born 1916 in Aachen, Germany. Following the rise of the Nazi regime, fled to Czechoslovakia, where he joined Maccabi sports club. In December 1941, deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. In September 1943, transported to the „Family Camp“ in Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he most likely committed suicide, after having learned about the murder of his pupils.

Lithograph

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

Born 1929 in Znojmo, Czechoslovakia. Following the German occupation in October 1938, her family fled and settled in Prague. In March 1943, deported with her mother to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. In May 1944, transported to Auschwitz and from there to Bergen Belsen, where she was liberated. Returned to Prague and in 1949 moved to Israel. Married and gave birth to three sons. Today lives in Tel Aviv.

Photograph of drawing

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

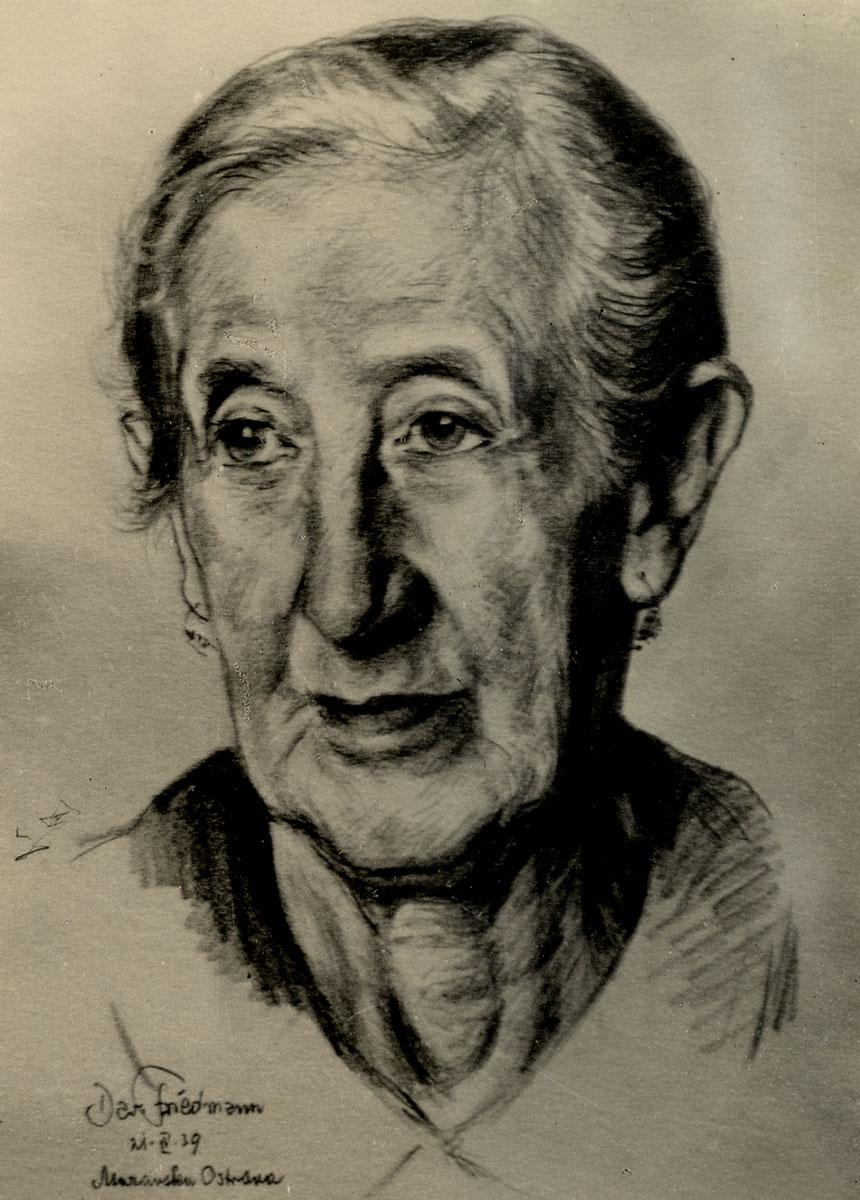

Born 1856 in Czaniec, Austro-Hungarian Empire, to the Rosenblum family. Lived with husband Heinrich and their four children in Moravská Ostrava. Died of starvation in December 1941, in the Jewish Home for the Aged.

Photograph of drawing

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

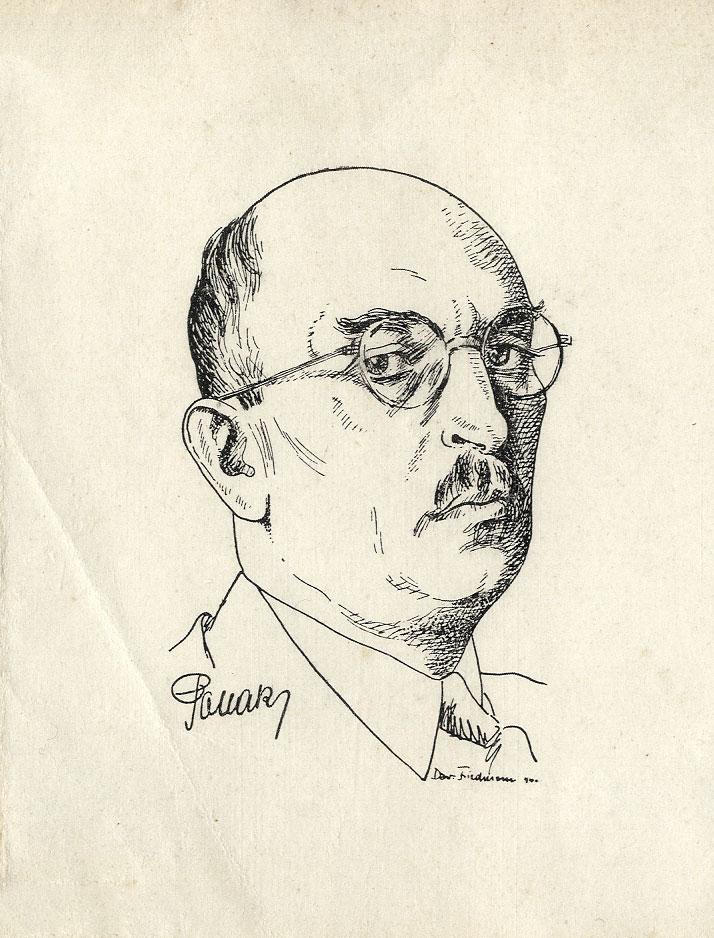

Worked in the Financial Department, Prague Jewish Community.

Born in 1895. In July 1943, deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. In September 1944, transported to Auschwitz, where he was murdered.

Lithograph

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

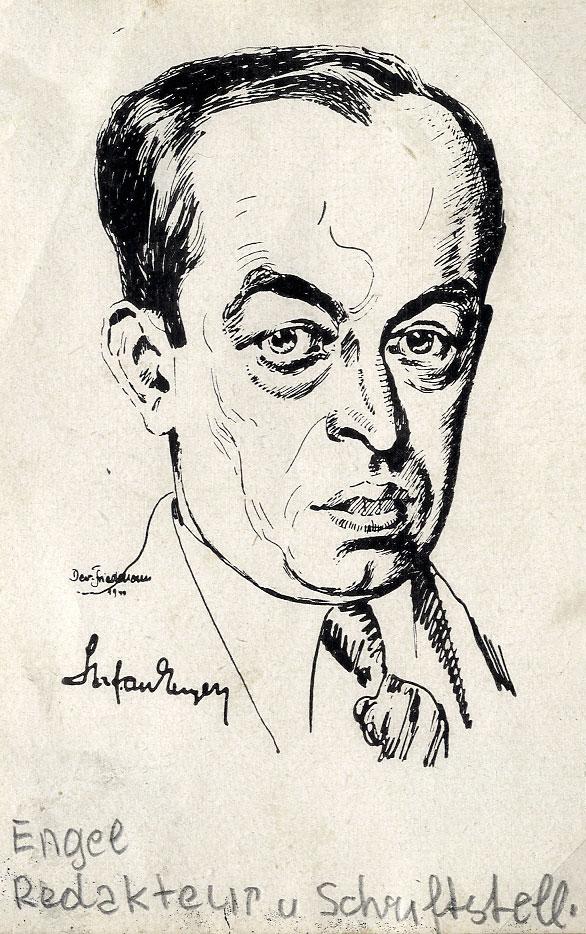

Writer, journalist.

Survived.

Lithograph

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem

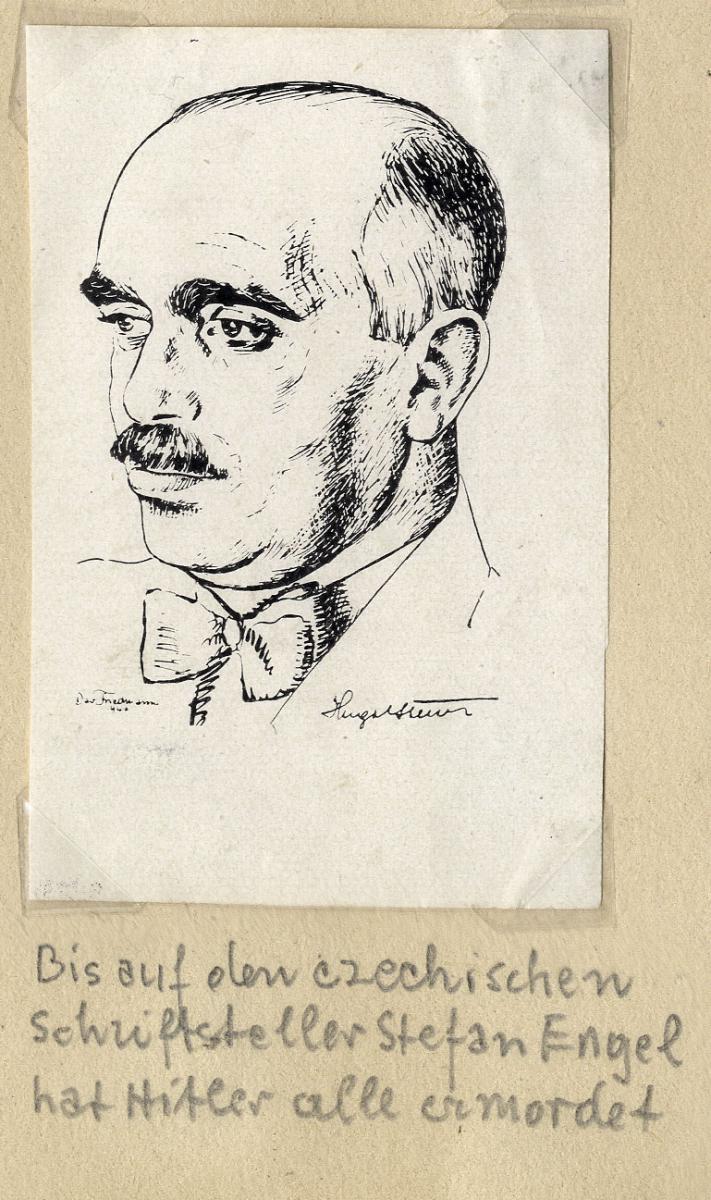

According to the artist, he was murdered.

Lithograph

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem