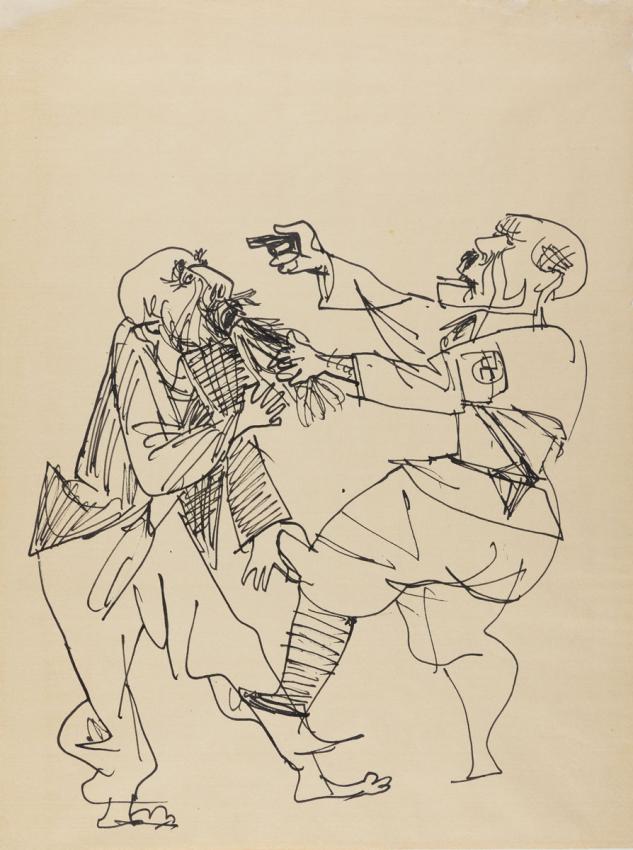

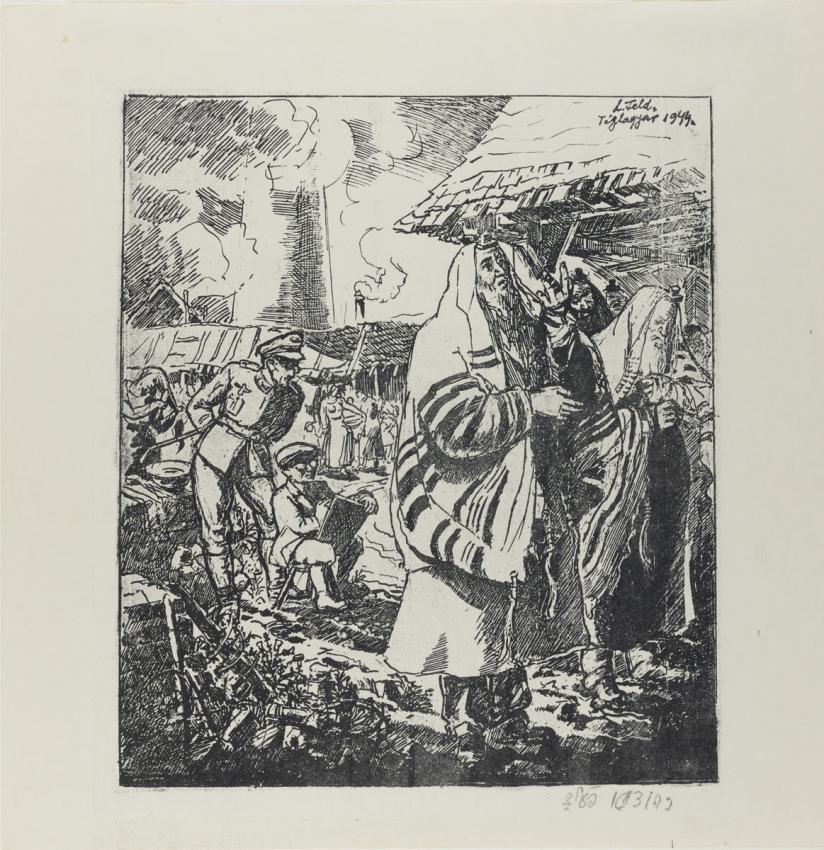

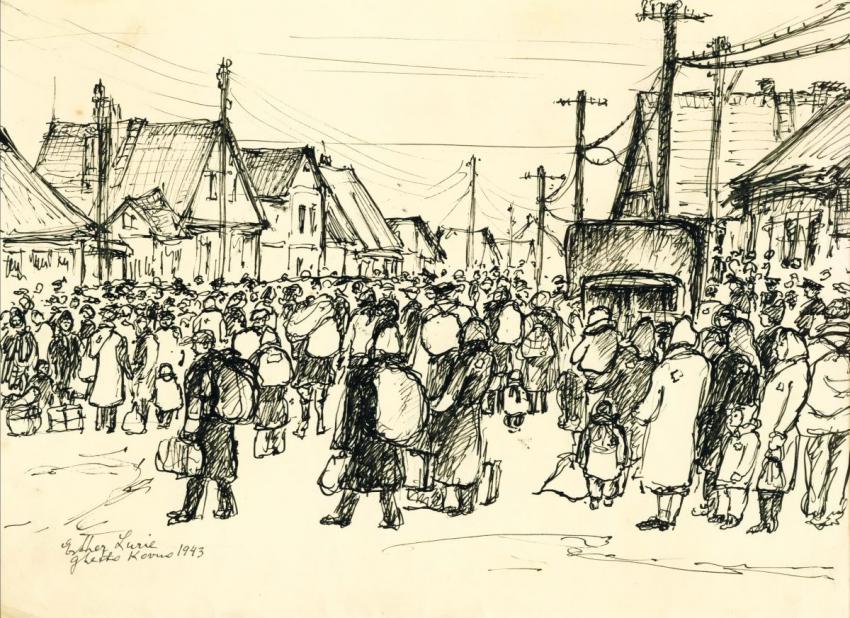

Many artists who were active during the Holocaust saw art as a means of protesting Nazi oppression. Some documented the armed struggle, and a few were even fighters themselves, but most used art in order to document the hardships they suffered on a daily basis. This exhibition presents a range of expressions of Jewish resistance from Yad Vashem's Art Collection in the framework of this year's theme for Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day: "Jewish Resistance during the Holocaust, marking 80 Years since the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising".

Creating art, safeguarding it and ultimately hiding the works were clandestine acts that artists during the Holocaust undertook at risk to their lives. In their drawings they depicted the locations where they were imprisoned with their families, the forced labor they were assigned to, the inhuman conditions, and the cruelty and humiliation they were subjected to, from the moment of their incarceration until their deportation to the extermination camps.

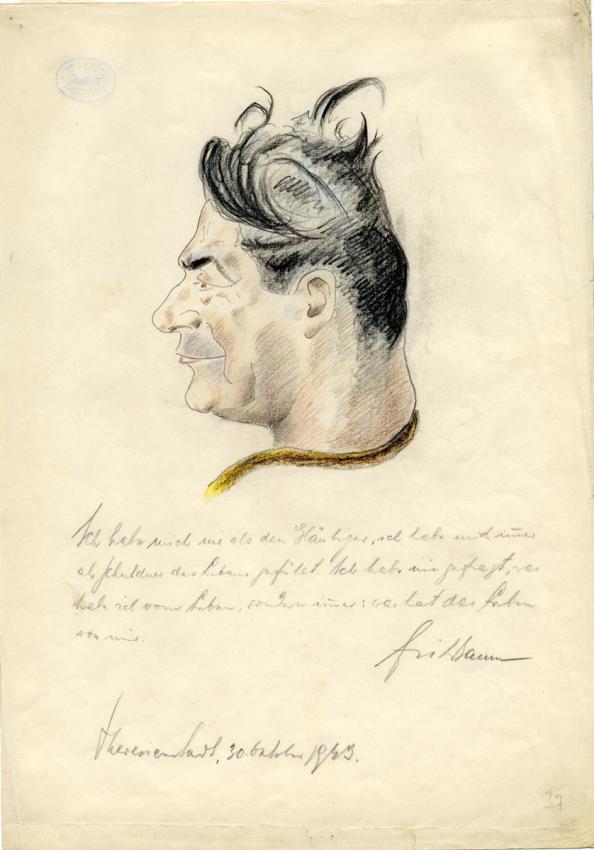

This documentation was their way of protesting and resisting the Nazi and collaborationist regimes, as explained by artist Leo Haas in his testimony. His choice to create art was motivated first and foremost by the imperative "to create indictments". At the same time, moments of humanity and faith in the ghettos and camps were also documented, a testament to the Jews' struggle to preserve their dignity, identity and culture. In Terezin, influenced by the satirical Czech tradition and the acerbic nature of German expressionism, irony was the weapon of choice to expose the cynical duplicity of this site, which served as a "model ghetto" for propaganda purposes, but was in reality a transit camp on the way to extermination.

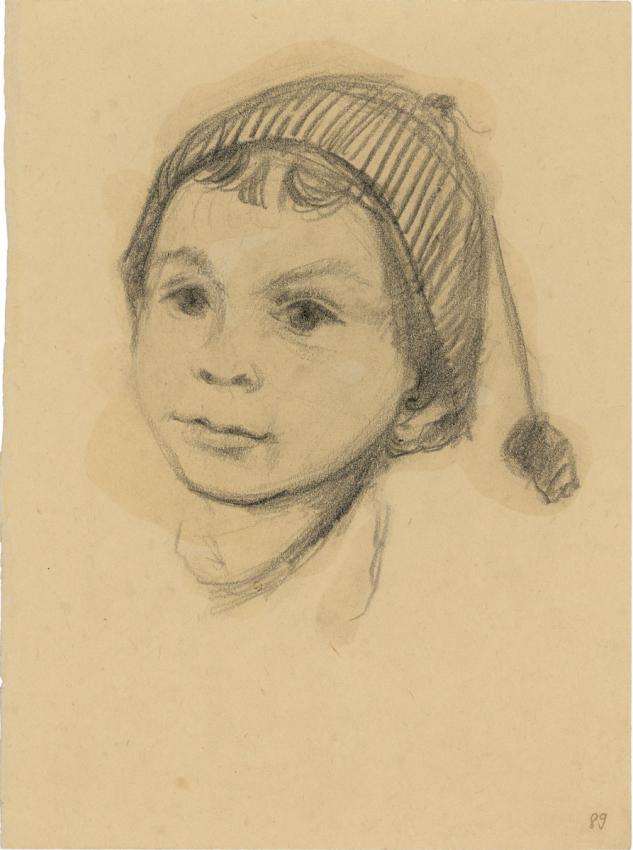

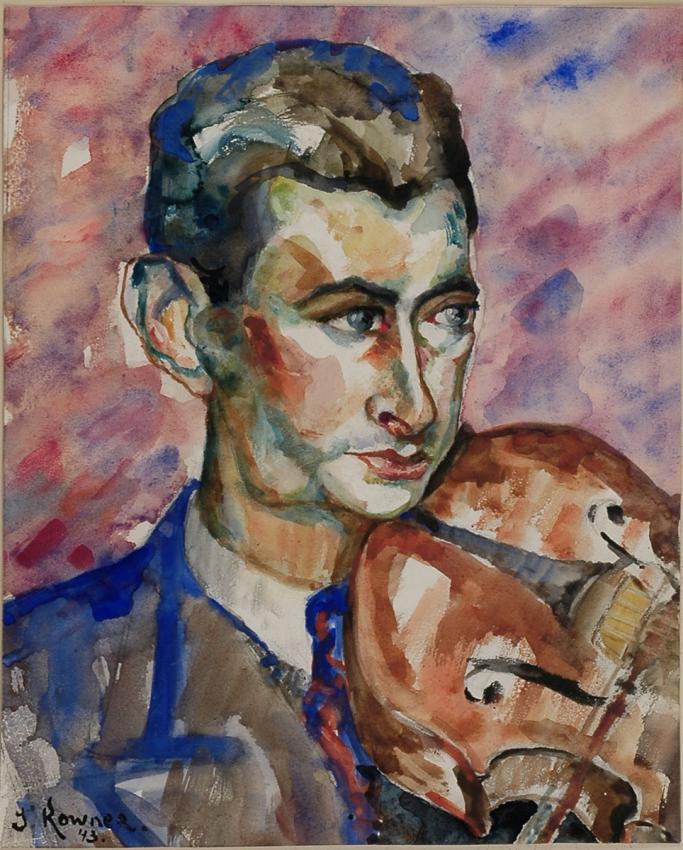

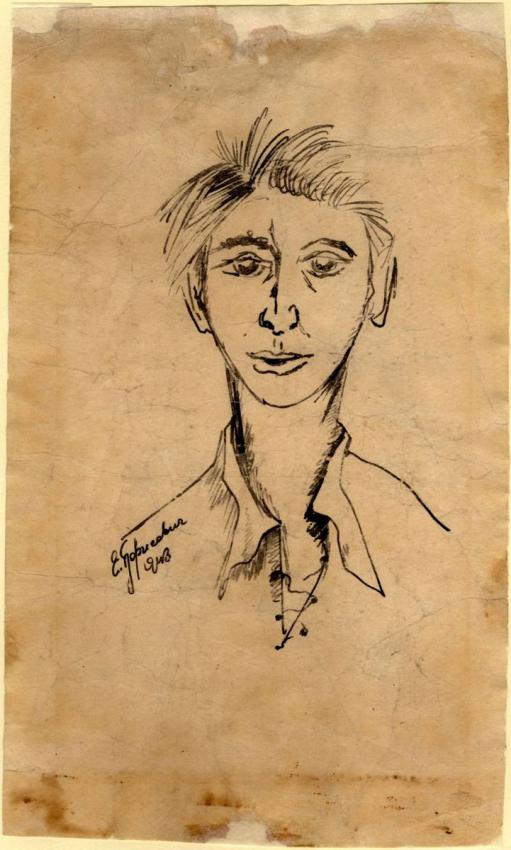

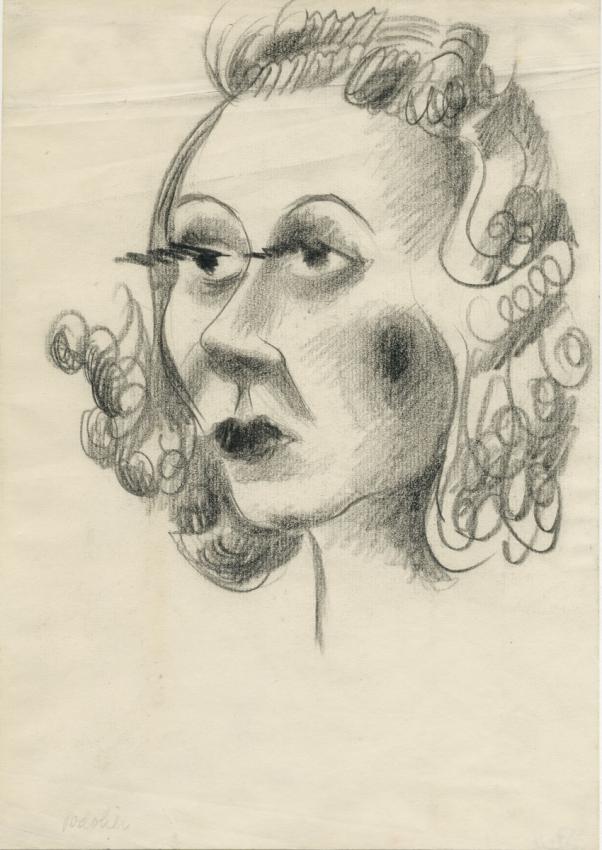

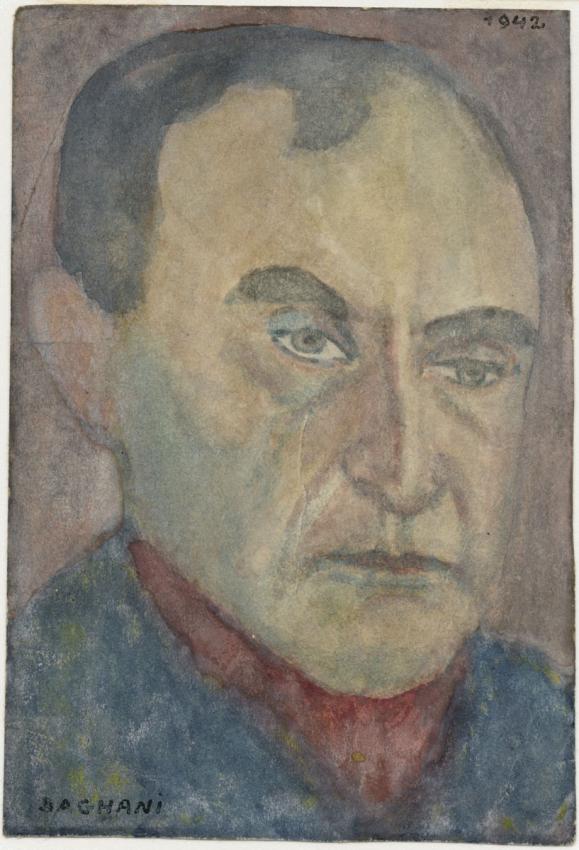

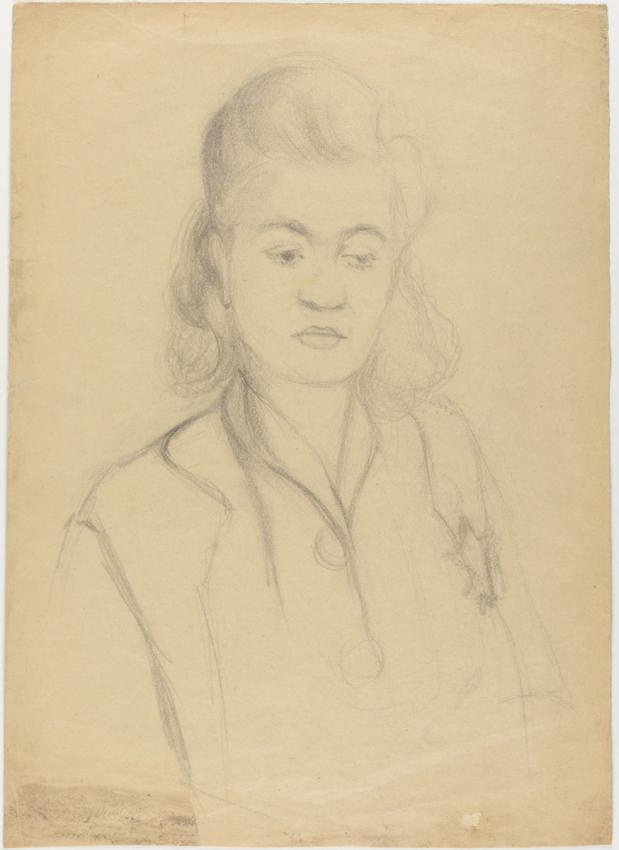

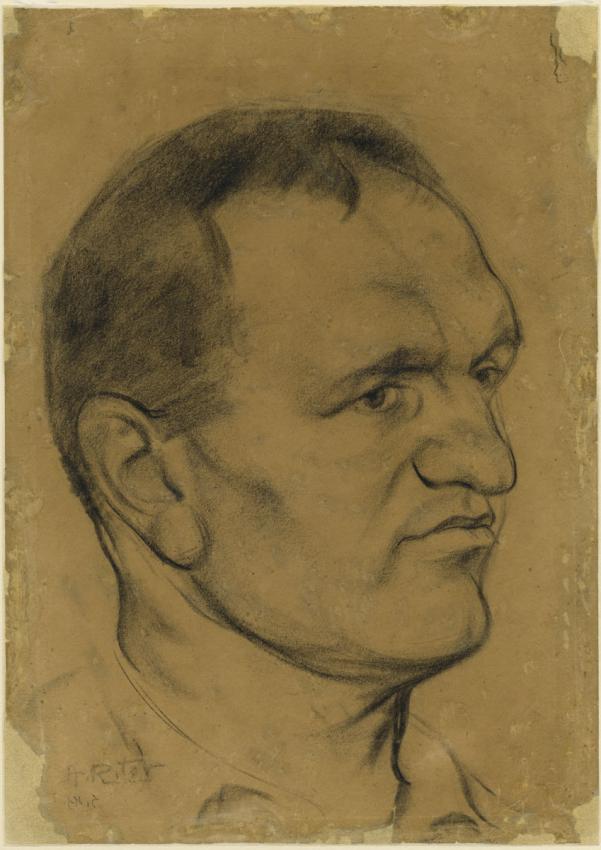

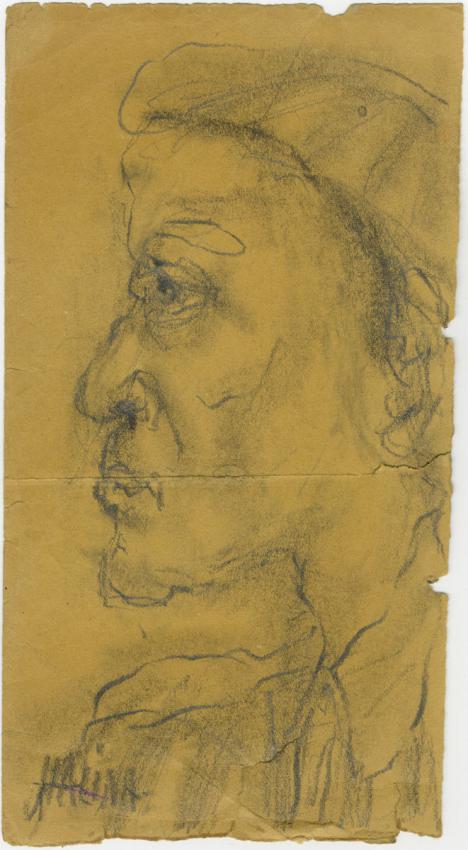

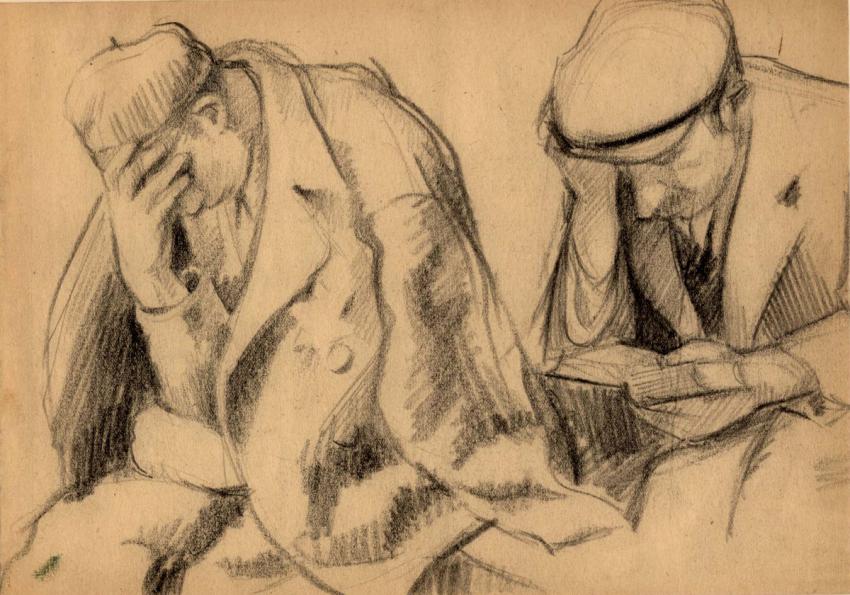

Of all the art that was created in the Holocaust and survived to reach us, portraits represent the broadest category. The mosaic of portraits on display in the exhibition, features men, women and children from different ghettos and camps. Among them we see resistance fighters and intellectuals; some are identified while others remain nameless.

These portraits embody the persistent struggle of the artists against dehumanization, erasure of individuality, murder and oblivion. The painters made do with the meager supplies available to them and recorded their comrades' features using pencils, charcoal or ink. The significance of these portraits was best explained by Meir Levinstein, whose likeness, and that of his fellow labor unit workers was captured at night after a grueling day's work in the Riga ghetto, by artist Arthur Ritov:

"…It was as if he [Arthur Ritov] had been sent to us to inspire each one of us with a touch of bravery and infuse us with vitality: as long as we are still alive, we are not to lose faith in the Jewish people and their survival."

* All artworks are housed in the Moshal Repository, Yad Vashem Art Collection