Nazi ideology not only blamed the Jewish people for the world's troubles, but also targeted every single Jewish child for annihilation – the most extreme expression of genocide. When the New Permanent Exhibition in Auschwitz-Birkenau was being devised, Yad Vashem approached world-acclaimed artist Michal Rovner to create a work for the space devoted to the 1.5 million Jewish children murdered during the Shoah.

Rovner decided not to build a tribute or memorial, nor to deal directly with aspects of the murder:

"At Auschwitz-Birkenau, we are already in the 'territory of murder'. Therefore, I wanted to create a space that will reflect the children themselves."

For over a year, Rovner studied the drawings and paintings made by children during the Holocaust. To this end, Yad Vashem created a special collection for her from its own archives as well as others around the world – most notably, the Visual Arts Collection of the Jewish Museum in Prague.

"One day, I was sitting at Yad Vashem looking at children's diaries and sketches from the Holocaust, and something struck me," Rovner says. "After seeing some of those drawings in frames, reproductions behind glass, I suddenly realized how much power there can be in just a small detail in the margin of the page. I decided not to change, or appropriate the drawings. I believe that no artist could produce any better work on the topic of children during the Holocaust than what the children themselves had already created. I wanted their authentic voices to be heard.

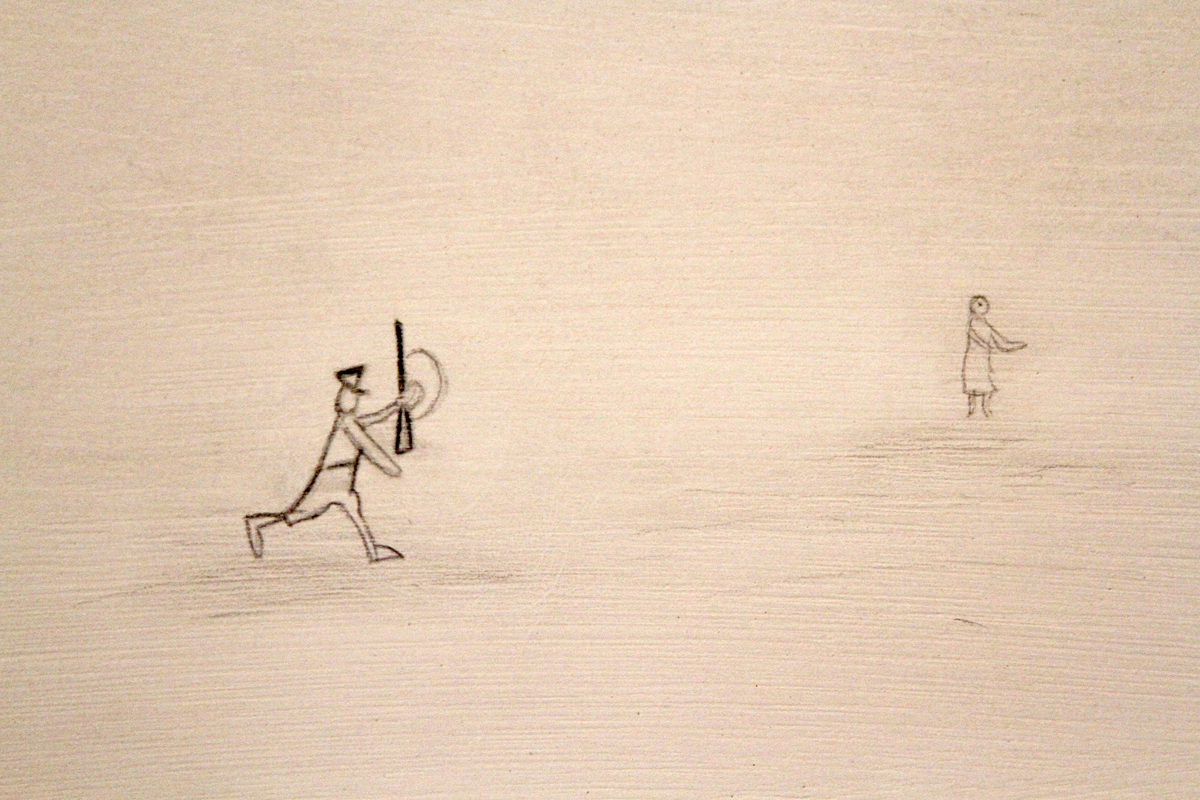

"Those children's families, homes, friends, belongings, landscapes and freedom had been taken away from them. Tragically, the vast majority of them left no sign behind them. Only very few were able to document the essential thing they were able to hold on to: their viewpoint. That is what is expressed in their drawings. Within a situation in which they had no choices, in front of a piece of paper they had a certain freedom to express themselves and the way they saw reality."

"One can almost feel the urgency of the situation in many of the drawings. They are reflections and details of the life they were forced to leave behind, and the new reality they encountered. These drawings are their legacy – and our inheritance."

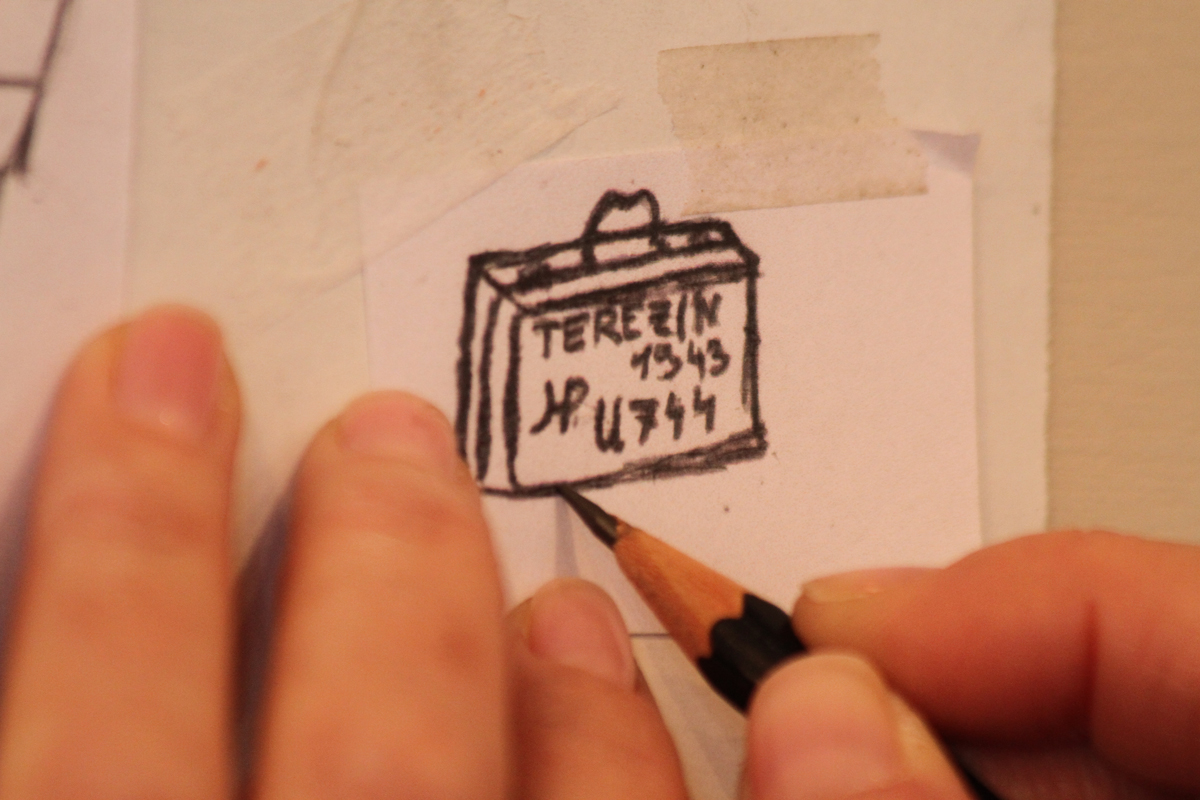

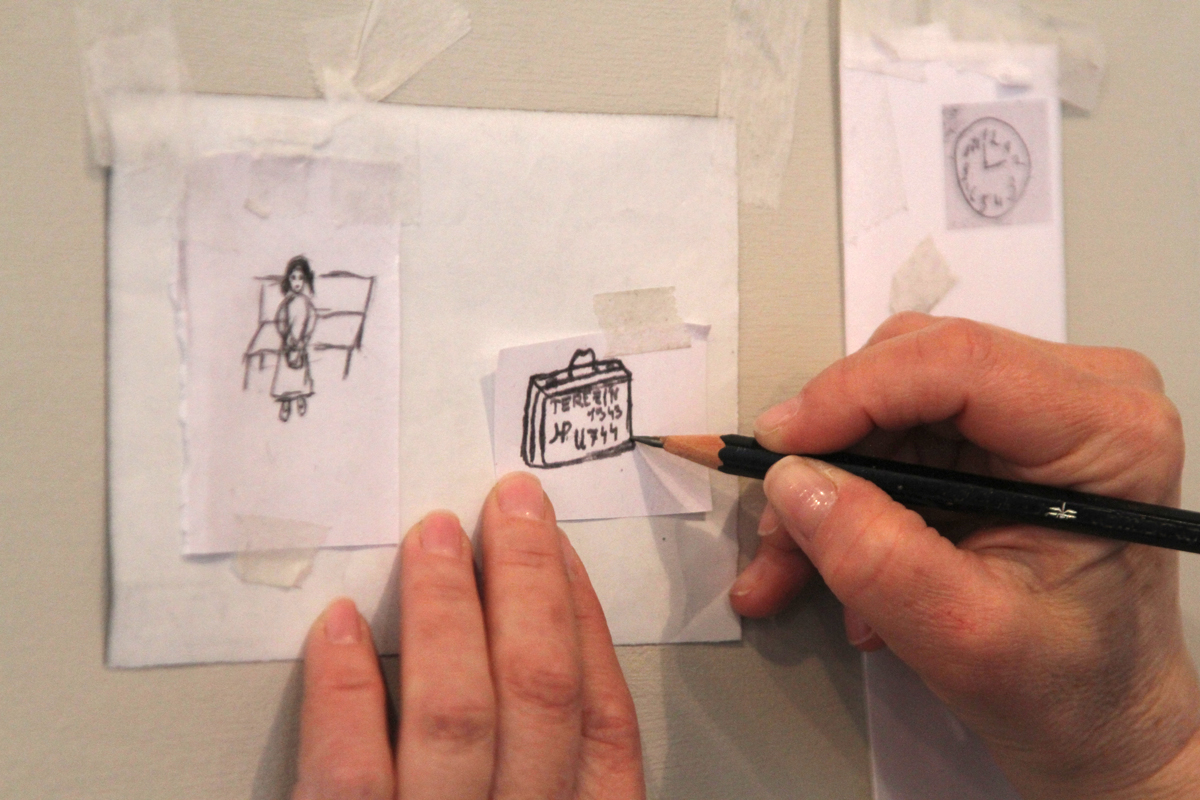

In order to study and orient herself with the vast amount of drawings and their elements, Rovner divided them into themes. She then assembled different fragments and small details, creating a composition that flows without telling a direct story.

Remaining true to her undertaking not to change or produce her own version of the drawings, Rovner decided to copy the fragments with a pencil, exactly as they were, onto the walls of the room dedicated to the children. "Children will draw on whatever they can – quite often, even on the walls surrounding them," she comments. With just a pencil and copy paper, one by one, detail after detail, Rovner drew each line again on a scale of 1:1. The drawings encircle the room, captivating and powerful. Together they give voice to the children's Shoah.

Original recordings of Jewish children from that period, singing, talking and playing, echo in the background, "appearing" and "disappearing." An accompanying text, composed especially for the exhibit by renowned Israeli author David Grossman, completes this unique effort to give presence to the world of the Jewish children, forever shattered by the Holocaust.

"The visitor enters an empty space in which nothing is displayed, only the footnotes of children's voices and some of their marks on the wall," concludes Rovner.

The delicateness, the fragility of these drawings is further magnified by the stark reality of the camp, viewed through the bare windows. These drawings and voices, these 'traces of life' are like hovering souls. They express a powerful testimony in just a few strokes of a pencil.