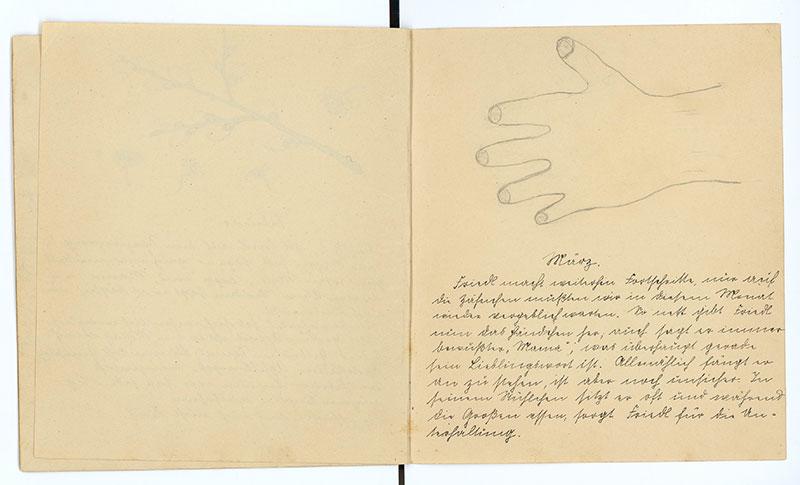

“There is much talk about keeping a journal. Everyone believes there is a great deal that needs to be documented, things that don’t happen in normal life... I sometimes want to take a pencil and do something with it, record some of what lies in the depths of my heart, a relentless force deep within my soul which lays beneath my consciousness.”

Extract from a diary by a young female prisoner in a forced labor camp during WWII

Long before liberation, the Jews who experienced the Holocaust yearned to describe their experiences in writing. Throughout the war, many of those trapped in ghettos and camps, in hiding and in the forests, recorded their feelings on scraps of paper often acquired at great personal risk. As their world crumbled around them and they were hunted and murdered in their millions, their personal writing and creative endeavors never ceased.

The act of writing also served as a form of escape, a temporary release from the killings and the torture, from the walls surrounding them and the crematoria whose smoke billowed relentlessly into the skies above. It brought comfort and reassurance that they remained human, and gave them the emotional strength to continue for yet another day. On discovering a hiding place after being pursued for several long months, one survivor testified: “Once again I was able to write and write, I just hoped I didn’t run out of paper… the paper and pencil allowed me to disassociate myself, to get away, and remember, even for a few hours, who I used to be….”

Often, their statements also served as a last will and testament, directed at those living outside the danger. Together with his friends and colleagues in the Warsaw ghetto, the young historian Emanuel Ringelblum laid the foundation for organized documentation during WWII by establishing the Oneg Shabbat archives. Through letters and diaries, as well as literary works and daily journals, the authors understood the importance of recording in great detail the events they witnessed, thus enabling the world — and future generations — to learn about the horrors they experienced.

With the war’s end, many survivors felt an immediate need to give testimony, to tell about the pain and suffering they went through, so it would never be forgotten or denied. They began by giving detailed accounts to spontaneously organized local committees, in refugee camps and before commissions of inquiry working to investigate the war crimes of the Nazis and their collaborators. In bulletins, newsletters and newspapers published soon after liberation, they told about life in the ghettos and the camps, about the invaders, about the aid bestowed upon them by their Jewish comrades and non-Jewish rescuers, about the nightmare death marches and the dreamlike moments of freedom. Testimony after testimony, the foundation was slowly laid for the archives that would document one of the greatest tragedies in recorded history.

In the wake of the early war trials, whole life stories began to emerge. As early as 1945, more than 30 survivors’ diaries were printed, with over 5,000 published since. To date, tens of thousands of written, audio and video testimonies have been recorded, thanks to the initiative of several individuals and organizations devoted to perpetuating the memory of the Holocaust, including Yad Vashem, which has the largest collection of survivors’ testimonies; the CDJC; and the Shoah Visual History Foundation. Each of these testimonies adds one more fragment of information about the Holocaust, one more piece in a picture of unimaginable cruelty and mass murder. The personal stories present the Jews as human beings, restoring their identities as well as touching their audience and enabling them to sympathize with their terrible plight. Although we cannot hope to “understand,” these accounts help illustrate the sights, smells and fears the victims experienced, and offer us insights into their all-too-human responses.

Personal testimonies have now become an influential and relevant genre in Holocaust, Jewish and Israeli literature, motivating generation after generation to partake in the act of remembering Holocaust victims. Survivors who relate their personal testimony to young people and educators from around the world are partners in perpetuating that memory, as well as the rich Jewish culture that was almost completely destroyed. Those of us who listen to them and publish their stories are no less involved in preserving this chain of memory: “Bearing witness, so they will know, until the last generation.”