"I am just a tiny spot, even under a microscope I would be very hard to see – but I can laugh at the whole world because I am a Jew. I am poor and in the ghetto, I do not know what will happen to me tomorrow, and yet I can laugh at the whole world because I have something very strong supporting me – my faith."

So wrote 14-year-old Rywka Lipszyc in a diary she kept in the Lodz ghetto from October 1943 until April 1944. Rywka was born in September 1929 in Lodz, Poland, the daughter of Miriam and Jankiel Lipszyc – descendants of a great Polish Rabbinic line. After losing her parents and siblings to disease and deportation, Rywka spent the remainder of the war with her cousins, Mina and Esther Lipszyc. After surviving the hunger of the Lodz ghetto, the horrors of Auschwitz and a grueling death march, the three cousins arrived at Bergen Belsen, weak and very sick. Esther last saw Rywka on her deathbed in the hospital ward. She and Mina slowly recuperated in Sweden, but they never again heard any more news of their cousin until last summer, when they were told about the diary, thanks to a Page of Testimony Mina submitted to Yad Vashem in Rywka's memory.

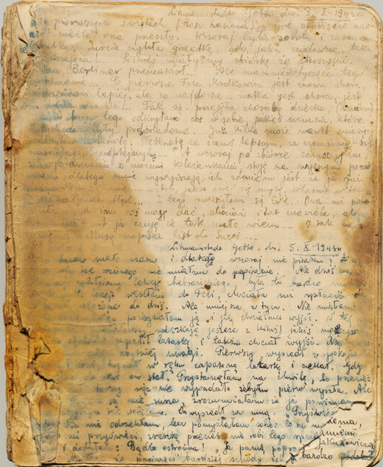

Rywka's diary was found in the ashes of the crematoria at Aushwitz-Birkenau in early 1945 by Zinaida Berezovskaya, a doctor who arrived at the camp with the liberating Red Army. The diary (in Polish, Yiddish and Hebrew) documented Rywka's daily life, along with her hopes, dreams and deepest emotions. Berezovskaya stored it in an envelope, along with a newspaper clipping about the liberation of Auschwitz. For over half a century it remained untouched, until Berezovskaya's granddaughter discovered it among her father's effects in June 2008 and brought it to the Jewish Family and Children's Services (JFCS) Holocaust Center in San Francisco.

Archivists at the center immediately began to investigate the identity of the diary's author, which ultimately led them to discover the Page of Testimony commemorating Rywka submitted by Mina Boyer in 1955 (updated in 2000). With the assistance of Yad Vashem staff, the family was contacted through Hadassah Halamish, Esther's daughter, who was deeply moved to learn of the diary's discovery so many years later.

For Esther and Mina, reading the diary has re-awakened painful memories of their wartime experiences, but it has also provided them with the strength to share the rich legacy of their family's faith, expressed so poignantly in Rywka's diary.

"I tried to cut myself off from it, but then suddenly it came back," said Mina. "I had a few sleepless nights, because I was re-living everything. But I will not give [the Nazis] the satisfaction that I cannot sleep. That I will never do."

Esther was the oldest of the cousins, who took on the responsibility for raising Rywka after her parents' death. She recalled how central the diary was in Rywka's young life. "It took me right back. There's even a section in the diary where she writes that I told her she shouldn't be writing. I was always telling her not to write because there were other, more important things to be doing, like running the house. I needed help."

In April 2012, San Francisco JFCS Executive Director Dr. Anita Freidman, a longtime supporter of the international Shoah Victims' Names Recovery Project, travelled to Israel to meet Esther and Mina and to allow the family to read Rywka's words from the original diary, which is planned to be published in the near future.

"I am terribly sad that I never had the opportunity to meet her," said Hadassah Halamish. "I know we would have had a lot in common. I have learned so much from her. Even under the most impossible living conditions, Rywka never lost the divine spirit inside her. Now she has returned to us again. Esther and my mother have had the honor of raising large families in Israel, thereby keeping alive the memory of the dead. Anyone who reads Rywka's diary will be a part of honoring her memory."