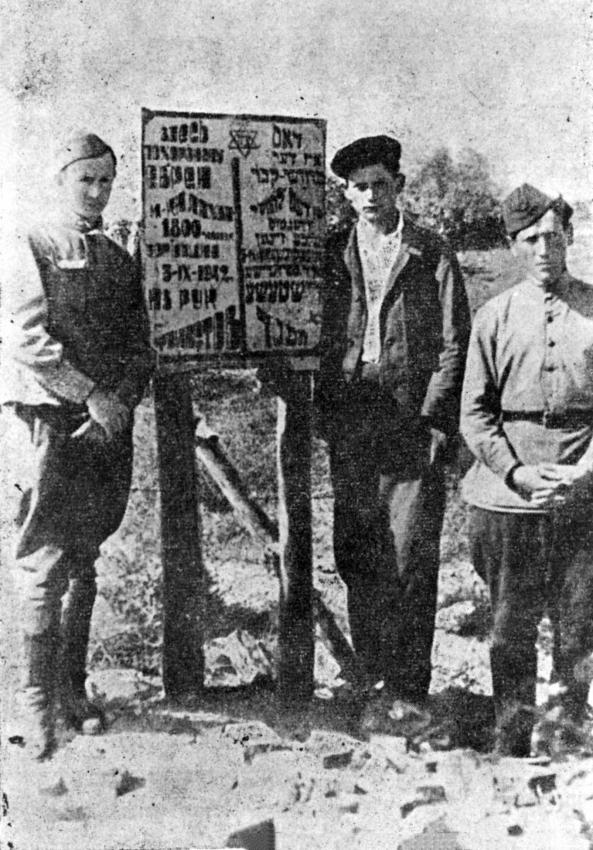

Jewish Red Army soldiers and a local survivor near the mass grave of Lachwa Jews, 1944

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 3488/47

“I had been at the front for quite some time and had seen all kinds of gruesome sights, but nothing can compare to what I see here. The dead bodies are piled up three meters high in deep ditches. Nobody knows the number of the dead – there must be as many as there were people in Liady. Here lie babies, children, and old people – all the Jews of Liady…”

So wrote Vladimir Pomerantsev, an officer in the Red Army and a former correspondent of a Yiddish newspaper, to the editors of the Soviet Yiddish newspaper Eynikayt (Unity). On October 8, 1943, Pomerantsev was among the group of Red Army soldiers to enter the shtetl of Liady in Belorussia – one of the first locations in the former Jewish Pale of Settlement to be liberated from the Nazis on Soviet territory. In the shtetl, the horrified soldiers witnessed the opening of a grave where 1,800 Jews had been murdered and buried on April 2, 1942.

An ethnic Russian named Izvekov wrote about the same event in a letter to Ilya Ehrenburg. Both the Jewish Pomerantsev and the Russian Izvekov remarked that people all over the world should know about the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazis. While Izvekov sincerely sympathized with the Jews who had been murdered, to him they were primarily Soviet citizens. In his letter, there was no indication that they had been killed because they were Jews.

In contrast, for Pomerantsev, the killing of the Jews in Liady meant the end of Jewish history, the physical destruction of the entire Jewish world. In his text “Sweet and Fatty Tzimmes” — he had been fed the traditional sweet carrot dish at some point in the local gathering hall of the Kolkhoz (Collective Farm) before the war — that dish becomes one of the symbols of the vanished Jewish past.

Pomerantsev was hardly alone in his perspective on the mass murder of the Jews. In June 1941, author and military correspondent Vasily Grossman chose not to travel to Nazi-occupied Berdichev to bring his mother to safety in Moscow. Her death during the Holocaust was one of the main traumas of his life. It was, therefore, not by chance that Grossman’s best-known novel Life and Fate contains a farewell “Letter from Mother” to Shtrom, the Jewish main hero of the book. In 1944, as soon as the opportunity arose again, Grossman traveled to his hometown of Berdichev where he learned of the circumstances of his mother’s death. Consequently, as co-editor with Ilya Ehrenburg of The Complete Black Book of Soviet Jewry, a shocking anthology of first-hand accounts of the Nazi mass murder of Soviet Jews assembled by Jewish Russian reporters at the end of the war, Grossman naturally penned the tragic fate of the Jews of his native Berdichev. Grossman’s story is among those included in Yad Vashem’s online project “Jews in the Red Army: 1941-1945.”

Earlier, in late 1943, Grossman published an article in Eynikayt entitled, “Ukraine Without Jews,” in which he expressed the same view as that of Pomerantsev about the Jewish world that no longer existed:

“In Ukraine, there are no Jews. Nowhere — not in Poltava, Kharkov, Kremenchug, Borispol, not in Iagotin. You will not see the black, tear-filled eyes of a little girl, you will not hear the sorrowful drawling voice of an old woman, you will not glimpse the swarthy face of a hungry child in a single city or a single one of hundreds of thousands of shtetls. Stillness. Silence. A people has been murdered.”

Mordechai Altshuler, Professor Emeritus of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and one of the leading researchers in the study of Soviet Jewry, pointed out that the Holocaust became a unifying factor for broad segments of the Soviet Jewish population. This was certainly true regarding Jewish soldiers. However, in their desire to fit in with contemporary Soviet modes of behavior, before the war a significant number of young Jews in the Soviet Union displayed little interest in their ethnic identity. “Nationality,” or ethnic affiliation, was formally indicated in Soviet identity papers, but it did not entail restrictions on a person’s education or career. Such an indifferent attitude toward their ethnic origin was characteristic not only of Jews born in the main cities Moscow or Leningrad, but also of Jews who were much more acquainted with the history of their families or who had grown up in a traditional Jewish environment.

An example of the latter was Benjamin Galiuz, who before the war had lived in the Vinnitsa Province in Ukraine. Galiuz served in the Red Army from the very first days of the war. After the liberation of Ukraine in 1944, Galiuz learned that his parents were among 44 members of his extended family murdered by the Nazis. Galiuz’s view of the events of the Holocaust were similar to those of Pomerantsev and Grossman. In a letter he wrote to Ehrenburg in 1945, Galiuz said: “I have travelled across almost all of Estonia, Lithuania, and Poland, but nowhere have I met a single Jew, only [deserted] little houses in towns and villages as if they were weeping for their [former] inhabitants.” This soldier’s nostalgia for the Jewish past was expressed even more forcefully when, during military operations in Poland, he found himself in the attic of a house where Jews had once lived. “I found many Jewish books which seemed to also be weeping for their owners,” he wrote. “I am not religious, but when I picked up a Passover Haggadah and began to read it, tears began falling from my eyes like rivers…”

“Jews in the Red Army: 1941-1945” is conducted within the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union at the International Institute for Holocaust Research, and supported by the Blavatnik Family Foundation.