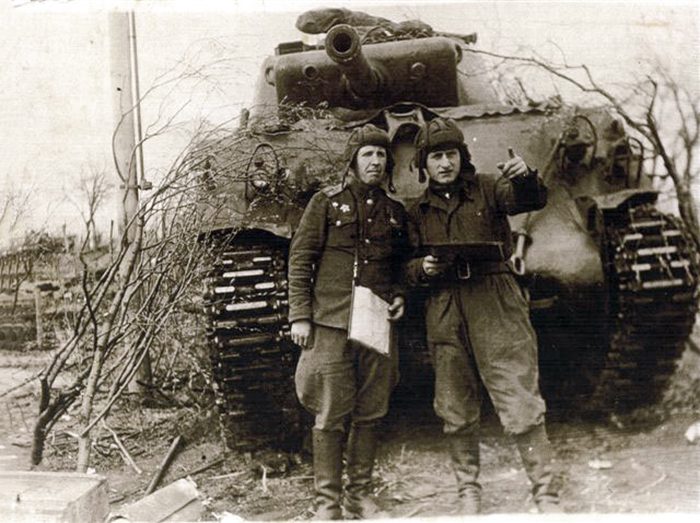

Abraham (Arkadi) Katzevman (Timor) was born in 1919 in the town of Dubossary. In 1936, after completing 7 years of Yiddish school in Dubassary (then Ukraine), Katzevman began to study at the technical school in Odessa but in 1939 he was drafted into the Red Army and sent to the Naro-Fominsk Military Armor school. During this time he changed his first name from Abraham to Arkadi in order to make his Jewish identity less obvious. At the outbreak of war on June 22, 1941 as a young officer with the 14th Tank Division he was sent to the Mogilev-Vitebsk-Smolensk area, from which the Red Army was retreating. During the battle for Smolensk he was gravely wounded. From October until December 1941 Arkadi Katzevman participated in the battle for Moscow. At this time he was awarded the Order of the Red Star. Arkadi was assigned to be commander of a special battalion of engineers and technicians to sabotage Soviet tanks and other military vehicles that had been captured by the Wehrmacht and from 1942 to be commander of a tank brigade that was sent to the besieged Leningrad. During one of the battles there Arkadi was very seriously wounded but, after several months in a military hospital, he recovered and returned to command his unit. In 1943 he was awarded the For the Defense of Leningrad medal, later the For Valor order and the Patriotic War order, 1st class. While fighting at the front, Arkadi found out that over 50 members of his family had been murdered by the Nazis, along with the other Jews of Dubossary in September 1941. Katzevman fought in the Baltic region, Poland and Germany. In March 1945 he received the Order of the Red Banner for taking part in the Red Army offensive in eastern Prussia. On May 12, 1945, when Arkadi was several kilometers from Prague, a message was received about the final capitulation of Nazi Germany.

One of his tasks in the Soviet occupation zone of East Berlin was to provide the German civilian population with food. Between 1945 and 1948 Arkadi Katzevman served as commander of the Dresden Armor Military School. While in Germany he made contact with the Haganah, the Jewish pre-state military organization (from 1948 the Israel Defense Forces), providing its staff with information and training materials related to military vehicles. In 1948 he was recalled to the USSR. Later, when he was discharged from military service, he moved with his family to Kaunas, Lithuania. After graduating from the local polytechnic institute as a mechanical engineer, he worked as a chief engineer and later a manager at a machinery repair factory in Kaunas.

In 1948, along with 14 other Jewish former Red Army officers Arkadi Katzevman wanted to volunteer to join the armed forces of the newly established State of Israel. Although he had not officially applied for permission to fight for Israel, in 1956 he was accused of Zionist propaganda and sentenced to imprisonment in a Soviet labor camp. He was released in 1959. He and his family then moved to Poland, from which, in 1960, they immigrated to Israel. In Israel Arkadi adopted the Hebrew last name Timor. At first he worked as a civilian employee for the Israel Defense Forces. Later, following the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War, he became one of the developers of the Tiran tank. He ended this career with the rank of colonel. Arkadi Timor was chief editor of the Hebrew book series "Facing the Nazi Enemy" and an editor of the Russian-language periodical publication "Words from War Invalids." He was also an author of the book My Comrades in Battle and of chapters in the book Jews in the Armies of the World. For over three decades Arkadi Timor was Russian-language military commentator for Kol Yisrael radiostation. The State of Israel awarded Timor The Underground Fighters Medal. He was a member of the Yad lashiryon (Armor Division Memorial) Association and one of the founders of the Israeli Museum of Jewish Fighters during the Second World War.

Arkadi Timor died in 2005 in Kiryat Ono, Israel.

Interview with Arkadi Timor

In a documentary film about his life made in Israel in the late 1990s Arkadi Timor recalled his deep grief at learning of the loss of his entire family and his profound sense of loneliness:

"The first thing in the morning that the soldiers at the front were waiting for was…to see the postman, [to receive] a letter [from their family and dear ones], [to see] whether they had received a letter or not. Do you know how it feels when you are waiting for such a letter… but I wasn't waiting for any letter [since all his family members had been murdered], they [the unit's members] ran to get [a letter], while I ran to my tank…. At that time my tank was my [only] home… the tank gave me the strength… I didn't have anything else [besides the tank]…. [But] you don't get any letters from a tank… and a tank doesn't smile at you"….

In referring to the moment when he received the information about the victory over Nazi Germany Arkadi Timor spoke about his great joy mixed with great sadness since he had no home to return to:

"… not far from Prague…. I suddenly felt that I was really alone… there was celebration outside…. I was sitting near a tank, watching my soldiers [dancing]… I … jumped into the tank… and cried [for a long time]… inside the tank. I suddenly felt that this was my only home [now] …while everyone else was already thinking of his home, somewhere [in the USSR]. Deep inside I felt that I was completely alone in the world…."

Arkadi emphasized that when he was in charge of providing the German civil population in East Berlin with food it was extremely important for him to demonstrate to the Germans that he was a Jew. He reportedly said:

"In Berlin heavy battles were fought. We knew that it was the end of the war. There was a moment when everyone acknowledged what he had lost and it was a time of calls for revenge.… I personally decided [otherwise] and gave the order… to provide food [to Germans] from two of my regiments' field kitchens. One was positioned at the Alexander-Platz, the other – 500 meters beyond. Soup was prepared around the clock and it was announced that children, women, and old people could come and eat, without showing any documents but on the condition that they should know that the commander of the unit that owned these kitchen was a Jew. It was very important for me that they should know that I was a Jew. I passed by those kitchens several times and I was greatly pleased with what I saw. This was my 'revenge'...."

From: Arkadi Timor: "The Combating Jew and a Dreamer" (Hebrew, accessed on October 3, 2014).