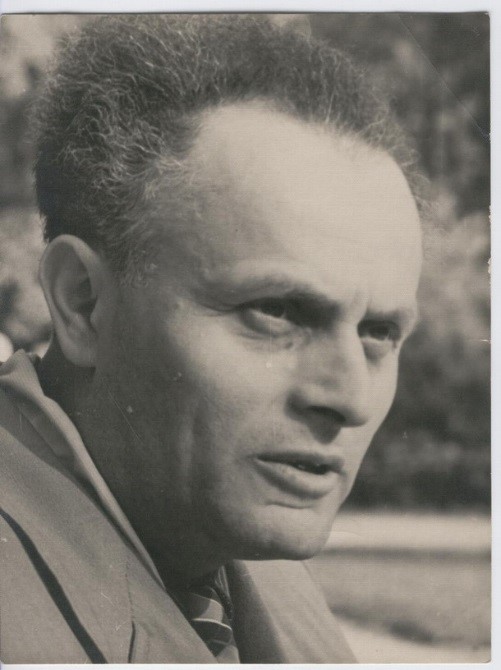

He was born in 1914 in Satanov, Ukraine, as Alter-Shulim Hershhorn (transliterated as Gershgorn in Russian documents), and was the eighth, and youngest, child in the family. His father, Solomon, a clerical worker, was killed in Kiev in 1919, during the civil war in Ukraine. Alter Hershhorn attended a seven-year Yiddish school, and then studied at a rabfak (lit. "workers' faculty", a preparatory school for university). In the mid-1930s, he graduated from the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics of Kharkov University, and defended a dissertation in the late 1930s.

Following the outbreak of the Soviet-German war in June 1941, Aleksei Gershgorn volunteered for the Red Army. He underwent training in a training camp near Moscow. From May 1942, he took part in combat, first in the battles for Kharkov, and later to the east of the city, in the territory of southern Russia. He served as platoon commander in the 499th Anti-Tank Artillery Regiment. In 1943, after taking part in the Battle of Stalingrad, he was transferred to staff service. Gershgorn served as deputy head of the HQ of the 5th Separate Anti-Tank Artillery Brigade, the head of its reconnaissance department. In 1943-44, he took part in the liberation of Ukraine, saw combat in Poland, and participated in the capture of Königsberg in 1945. Gershgorn ended the war in the rank of major, and was awarded four military orders and a number of medals.

From November 1941 on, Gershgorn wrote a diary, even though such activities were strictly prohibited by the Red Army.

Aleksei Gershgorn's brother Mikhail (born 1905) was seriously wounded in frontline combat in November 1942: his right leg was amputated; his left leg was left paralyzed, and he became blind in one eye. Four of their siblings were killed under the German occupation. As Aleksei noted in his diary, at least Mikhail would be able to have children, who would carry on the Gershgorn family line.

After the war, Gershgorn continued to serve in Western Ukraine for a brief while, before being discharged from the army and settling in Lvov. In 1946-78, he held the Chair of Mathematics at the Lvov Trade and Economy Institute (University). He authored several textbooks on linear optimization and other subjects. Aleksei Gershgorn died in 1985.

From Gershgorn's diary, the entry for November 28, 1941

"This night, I had a strange, and rather sad, dream. I was sitting in an auditorium during a meeting of some kind. An aged Jewish woman writer is speaking to the public, discussing the horrific atrocities that the Germans are committing against the Jews… The pictures drawn by her seem familiar to me. These are episodes from the Proskurov bloodbath [i.e., the bloody pogrom perpetrated by the Ukrainian nationalist army in the town of Proskurov in 1919]…

I woke with a heavy heart and remained sleepless until morning, trying to solve the accursed riddle: why, of all the peoples of the world, has God chosen mine? What did my poor people contribute to the evil spirit of humanity, that it should spill its innocent blood throughout the centuries?...

[On a vision of Jewish refugees somewhere in Russia] … And how odd it is that thousands of people of various ethnicities have become refugees, and they suffer all the hardships that can befall a human being. Still, it is the fleeing Jews who present the saddest spectacle, and not because they are poorer than the rest. The land on which they have set foot is just as alien to them as it was before [the Revolution]. This foreign land fills their souls with fear, fear of the unknown. They have been uprooted from their native soil.

A poor people! Throughout the centuries, under the pretext of various visions of "good", they have been mistreated and decimated. Nevertheless, they still exist. Moreover, they are more alive than any other ancient people. However, they need a land of their own, a land which they could touch to restore their strength, like that ancient hero".Sokhrani moi pis'ma…, vol. 3, eds. Ilia Altman, Leonid Tiorushkin. Moscow, Tsentr "Kholokost", 2013, pp. 158-159Sokhrani moi pis'ma…, vol. 3, eds. Ilia Altman, Leonid Tiorushkin. Moscow, Tsentr "Kholokost", 2013, pp. 158-159