David Dragunskii was born in 1910 in the village of Sviatsk in Chernigov Province. His father was a tailor. After completing school in Novozybkov, the closest town to Sviatsk, Dragunskii moved to Moscow, where he worked as an unskilled laborer on building sites. His public activity led to his joining the Communist Party in 1931. He was one of the urban residents who were sent by the Soviet authorities to rural areas to carry out the collectivization of the peasants.

He was drafted in 1933 and in 1936 he graduated from a tank school. Then he served in the Trans-Baikal area, where in 1938 he participated in the Soviet-Japanese military conflict at Lake Khasan. For his role there he received his first Order of the Red Banner. From early 1939 until June 1941 he studied at the Frunze Military Academy. He began the war as commander of a tank battalion, and then fought near Smolensk, in the Caucasus, and at the battle of Kursk in the summer of 1943. In October of that year, with the rank of lieutenant colonel he became commander of the 55th Tank Brigade. In that post he participated in battles in Ukraine, including for the liberation of Kiev. He was then recommended for the highest honor of Hero of the Soviet Union, but instead received his second Order of the Red Banner. Dragunskii was seriously wounded in December 1943. While recovering, he learned that all his relatives who had remained in Sviatsk had been shot to death by the Germans and that his two brothers had fallen in the Red Army.

After being released from hospital, Dragunskii returned to his brigade and took part in the liberation of the rest of Ukraine. In September 1944, for bravery displayed at the crossing of the Vistula and in capturing and holding the Sandomir bridgehead, Colonel Dragunskii was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

In the second half of April 1945 Dragunskii took part in the battle of Berlin and then his brigade rushed on to help liberate Prague. For his role in those two operations, on May 31, 1945, i.e., after Germany's surrender, Dragunskii was honored a second time as Hero of the Soviet Union. On June 24, 1945 he took part in the victory parade on Red Square in Moscow.

After the war Dragunskii graduated from the Higher Military Academy and, soon thereafter, received the rank of major general. Several years later he was promoted to lieutenant general. He commanded tank divisions and an army in the Trans-Baikal areas and from 1965 to 1969 was first deputy commander of the Trans-Caucasus Military District. In the latter year he replaced General of the Army Iakov Kreizer as head of the Vystrel Higher Officer Courses. In 1970 he received the rank of colonel general. He retired in 1987.

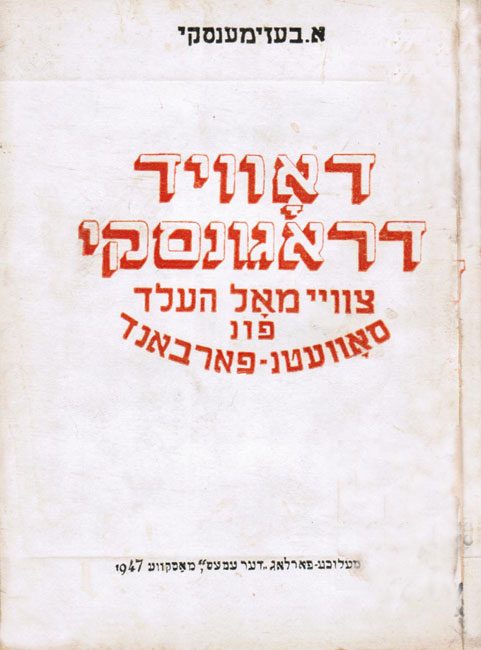

From a Jewish perspective Dragunskii was a complex figure. On the one hand, he was not ashamed of being a Jew, as indicated by the fact that he did not alter either his first name or his patronymic, Abramovich, to something more Russian sounding. In the atmosphere of postwar Soviet antisemitism this was significant. During the war he had been an active member of the Jewish Anti-fascist Committee (JAC). For the Soviet Jewish intelligentsia he became one of the main symbols of Jewish heroism. On June 16, 1945 he was featured at a meeting with representatives of this intelligentsia at the Moscow conference hall of the JAC. Dragunskii was given a gold watch that had been sent by a Jew from Chicago as a gift for the most outstanding Jew in the Red Army. In his speech the hero stated: "I smashed the Germans with appetite and desire. I smashed them as a commander of the Red Army and as a Soviet citizen. Furthermore, they were beaten by the Jew who lives in me and who is fiercely taking revenge on then for torturing and abusing the Jewish people." In 1944 Dragunskii proposed to Shlomo (Solomon) Mikhoels, the head of the JAC, that the Committee should concern itself with the mass burials of Nazi-murdered Jews around the country, but this project was not realized. At the end of the 1940s, with support from the local authorities, Dragunskii organized the reburial of the remains of his family members from the murder site in Sviatsk to the Jewish cemetery in Novozybkov. In 1947 Der Emes publishing house issued Alexander Bezymenskii's Yiddish book David Dragunskii - Twice Hero of the Soviet Union. In 1947 Dragunskii wrote a letter in which he described himself as a Jew who was happy about the USSR's support for the establishment of a Jewish state. He stressed the significance of the latter for the Jewish people, particularly after the many Jewish victims killed during the Second World War. At the end of his life Dragunskii confirmed that post-war antisemitism in the USSR had slowed his military career.

Nevertheless, in 1983 Dragunskii agreed to serve as chairman of the KGB inaugurated and controlled Soviet propaganda organ, the Anti-Zionist Committee of the Soviet Public, of which many well-known Soviet Jews were members, at least formally. Dragunskii signed many declarations of this committee even when he did not write them himself and often defended the official anti-Israel position of the committee. Dragunskii opposed the emigration of Jews from the USSR, believing that Israel's policies and the emigration of some Jews from the USSR would cause problems for the remaining Jews. At the same time, he supported cultural initiatives within the extremely restricted framework of officially permitted Jewish activity in the Soviet Union. Despite Gorbachev's perestroika, the thaw in relations with Israel in the late 1980s, and the end of the policy of state antisemitism, Dragunskii continued to head the Anti-Zionist Committee until his death in 1992.

Four decades earlier, in 1951, a bust of the two-time Hero of the Soviet Union had been set up in Dragunskii's home town of Sviatsk. In 1995, when the population of Sviatsk was resettled after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the bust was transferred to Novozybkov.

Letter of David Dragunskii to Shlomo Mikhoels

On December 4, 1945 David Dragunskii sent a letter to Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee chairman Shlomo Mikhoels in which he wrote:

"After four years of war, I had the opportunity to visit my native region – my home town Novozybkov and Svyatsk, the village where I was born….

For in my home town the German fascist monsters executed my entire family – 74 members of the Dragunsky family in all. But what especially saddened me was that no graves were arranged. The little bones of my sisters and children are scattered about the fields. Cattle trample them – in a word, all human dignity is lost.

And in the village council there is no list of how many, when and who were murdered.

It's true that at my insistence they are now taking action, but these facts induced me to write you a letter and raise the question of delegation to the Anti-Fascist Committee the work of setting up monuments for the executed children, old people, and women.

There are murdered victims of fascism in all cities, towns and villages. There are no graves. Often cattle graze in the fields where human bones are scattered. This doesn't only refer to Jewish victims, but also many partisans, executed children, women, and old people are not buried. You will be doing a great and necessary service through such work. The humiliated victims and the fascists' unheard of degradations will not be forgotten for centuries. It is difficult to forget the four year nightmare. We must erect fences, monuments, and inscriptions everywhere and show dates….

Please raise this question before the responsible organizations.

I pledge to offer you any support I can in this undertaking …"

From: Shimon Redlich, War, Holocaust, and Stalinism: A Documented Study of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in the USSR, Luxembourg, 1995, pp. 231–232.