David Kostinboi was born in 1926 in the village of Kornytsia, Ukraine, close to the Soviet-Polish border. His original last named was Kostinboim. When he was five years old, his family moved to the shtetl of Kunev, located on the border. When the Soviet-German war began in June 1941, the family did not want to leave. David's parents did not believe the rumors about what the Germans were doing to the Jews. However, when the enemy approached Kunev, David's mother had a bad premonition so she put some food to a sack and gave it to David saying, "Run away!" David fled from the doomed town with the retreating Red Army and then, at the age of 15, he experienced the humiliation and dangers of the Red Army's retreat of 1941.

By a miracle, David succeeded in escaping from the advancing Wehrmacht and reaching a village in the Urals far from the frontline. There he worked in a kolkhoz, and learned to perform all kinds of peasants work. A year later, when he was only 16, David was summoned to a recruitment office and "advised" to volunteer for the frontlines. He recalled:

"I was never super-patriotic, and I did not join [the Red Army] in order to fight for the Soviet regime. I was going to fight against fascism. And, of course, I wanted to take revenge for my family. I assumed that it was most likely that the Germans had already killed all my relatives. And that was indeed the case. However, it was not the Germans who shot the Jews, but residents of our town ... It was Ukrainian policemen, former neighbors of the doomed, who did that."

From the interview taken from D. Kostinboi in 2006

It was at the recruitment office that a clerk changed David's Jewish-sounding last name Kostinboim to the more neutral Kostinboi ("–boim?! And if, God forbid, you are captured as a POW?"). The official also recommended that David change the nationality in his documents from Jewish to Ukrainian but David refused.

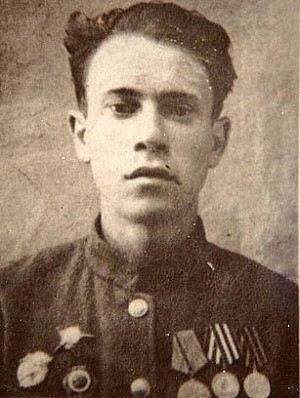

David's training lasted for half a year. In October 1943 Private Kostinboi was assigned to be a machine-gunner in an infantry regiment deployed in eastern Belorussia. He recalled that being a machine-gunner was the most dangerous assignment in the infantry since in every battle the enemy first tries to kill the machine-gunners or at least put them out of action. War revealed itself to David Kostinboi as a phenomenon in which every day people were killed in the hundreds and thousands, commanders did not spare soldiers, and therefeore value of human life was nil. Kostinboi fought in Belorussia, then in Lithuania and, later, in Eastern Prussia. He was wounded several times, in the eyes. As a result he was blind until doctors succeeded in partially restoring sight to him. He finished the war being able to see with only one of his eyes.

The episode with the clerk at the recruitment office in the Urals to some extent was repeated at the front. On one occasion, his battalion commander sent several volunteers, including Kostinboi, to the enemy rear, to capture someone to provide information. The commander ordered the volunteers to hand over all their documents to his orderly. David did not want to do so. The commander retorted: "You should be the first to leave his documents since you are going to penetrate behind the German lines." David replied: "If I am taken prisoner, as soon as the Germans selected their Jewish prisoners to execute them, I will step forward and accept with pride being killed for my people." The commander shook his head, remarking: "What a fool you are!"

Kostinboi met VE-Day in Eastern Prussia. He recalled that the following day, May 9, he awoke, with a heavy hangover after the VE-Day celebration, on a military train. Finally, he realized that he was being sent to the Far East, to fight against Japan. Kostinboi was released from the army in December 1945.

Only one of his sisters succeeded in escaping from Ukraine and surviving.

After the war, Kostinboi worked as a teacher at a village school in western Ukraine.

Additional information

Private Kostinboi guards German POWs

"Once I was called by the commander of our company, who ordered me to escort two German prisoners. He said to me: 'Son, while all is quiet here, take them to headquarters. Be quick about it, there and back, half an hour is enough for you'. He knew that all my relatives had been shot to death by the Germans. He gave the orders for half an hour even though the HQ was seven kilometers away. Perhaps he wanted me not to take them to the rear, but to shoot them while they 'were trying to escape.' The Germans had been encircled. They were dirty and emaciated, and in their pathetic rags, they resembled homeless people in a city. One of them was a young boy with a long neck and sad eyes. His name was Rudi, and his companion was an elderly German, a gloomy type, whose name was Kurt.

On the way, I started talking with them. I knew German fairly well.

From my accent, they immediately realized that I was Jewish. The Germans were overcome by terror. Rudi began to talk about his fiancée, Kurt - about his children. All their words were permeated with despair and pleading for me to spare them: "We did not kill anyone," "We did not shoot anyone," "I'm a worker" ... I did not finish anyone off ...

Even when they realized that I was not going to kill them, they continued to cringe before me, displaying their willingness to do anything I asked, trying to win my favor. Their sense of desperation did not abandon those Germans.

Their subservience and wretchedness struck me. At my slightest shout they shuddered […] before me, a boy in a Red Army uniform. I handed over the prisoners to headquarters and two hours later returned to my battalion. When I reported to the company commander how I had carried his order, he looked at me with respect."

From the interview taken from D. Kostinboi in 2006

Antisemitism at the front

"On the front lines, in the trenches – people usually did not pay attention to your nationality [i.e. ethnic identity].

But once a phrase uttered by my second in command dumbfounded me! A guy from the Siberian hinterland, he had fought with me for about two weeks. We had just dug a trench and sat down to smoke when he said: 'The Yids do not fight!'.

How painful it was for me to hear such a thing! ...

The company was then commanded by [the Jew] Senior Lieutenant Shvartsur; fifty meters from us, with another crew, there was a Jewish machine-gunner named Anshel. Furthermore, I was facing death every day with this Siberian and sharing all the hardships with him, but for him this did not matter – 'The Yids do not fight!' " I cursed him rounding with all the obscenities I could think of ..

He then apologized for quite some time, saying that he did not know that I was a Jew because in Siberia the name David was often found among Russians. I did not feel any better after his explanations.

On another occasion the Party organizer [partorg] of our battalion came to our forward trench. We were on the defensive. He approached my crew and said: 'I suspect that Your machine gun does not work'. I countered: 'Everything is normal, it works like a Swiss watch.' The Party organizer said: "Fire a burst and we will see." I immediately warned him what would happen when I fired at the Germans, [after all] they were so close to our position.[…]. He shook his head and said: "Shoot anyway." ... I shot half a belt of cartridges at the Germans and, in response, there immediately began such a shelling that the sky seemed to be falling on our heads. The Party organizer, who was then lying next to us side at the bottom of the trench, said: "You are a good fellow, even if you are a Jew!". I couldn't take this and shouted at him: "I don't care about your opinion! As a Communist and an officer, you should be ashamed. Where is your conscience?' … After the shelling, I became even more angry. The Party organizer quickly darted into a nearby passage and disappeared from my sight.

After this incident, he consistently avoided me and it is quite likely that he was right to do so ...".

From the interview taken from D. Kostinboi in 2006