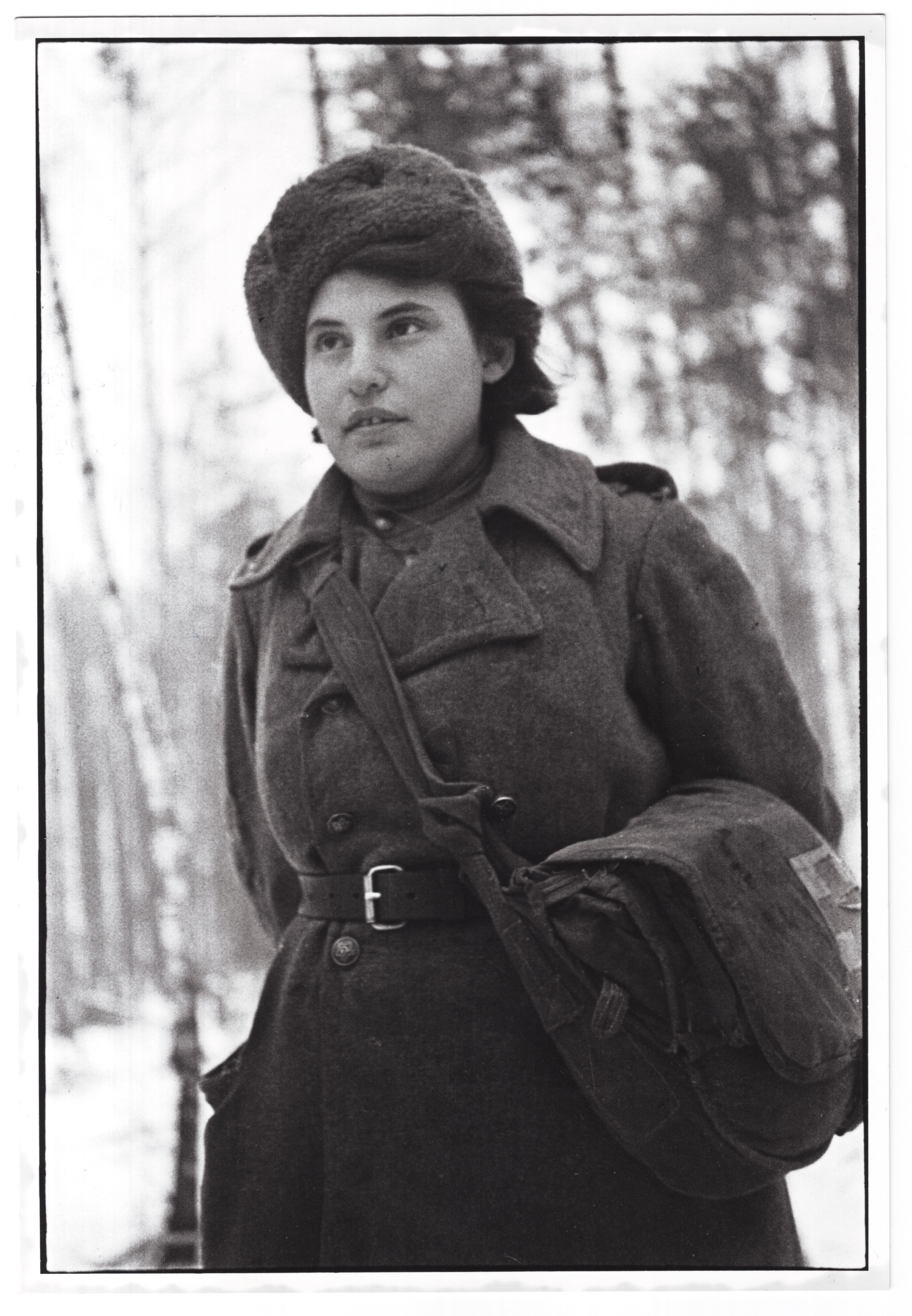

Dvoira Nemirovskaia was born in Odessa in 1923. When she was two years old, her mother died and her father Motl, an engineer, moved to Moscow. Dvoira lived in Moscow from 1926. Later her father remarried, to a woman who had a son from her first marriage. Motl adopted him and gave him his last name. Dvoira failed to establish good relations with her step-mother, but really loved her elder "adopted" brother Lev Nemirovskii. Lev was conscripted into the Red Army in the late 1930s, but was dismissed from service because of some medical problem with his legs. Later, when Dvoira was drafted for the military service, Lev, who lived separately from his family, learned about this and sent a letter to her at the front. He wrote that he was ashame that she was fighting and he was not. Despite his exemption from military service, Lev volunteered to join the Army and was accepted. He was killed near Smolensk, in western Russia, in 1943.

In June 1941, after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, together with other members of the Komsomol (Young Communist League) Dvoira appeared before the district committee of the Komsomol and demanded to be drafted into the Red Army. Instead, they were mobilized for work at various Moscow factories. Dvoira, whose Yiddish name had officially been changed to the more Russian-sounding Dora, was sent to the Krasnyi Proletarii military factory as a quality controller.

Nemirovskaia was drafted for military service as a nurse in May 1942, but got to the front only almost a year later. Just after she had arrived at a medical bunker there, she was lightly wounded and deafened by an artillery shell. Nevertheless, Dora continued to help the wounded soldiers. She later remarked that there was something positive in losing her hearing: she could not hear the terrible screams of the wounded. Later her hearing was restored.

Nemirovskaia carried dozens of wounded soldiers – mainly men heavier than she was – from the battlefield, and cared for many dozens of others under enemy fire. The instructions for nurses ordered her to move in the battlefield only by crawling, but she recalled that when she heard the screaming of a wounded man, she stood up and ran across the field. She remarked that the Lord in heaven must have decided that she was going to survive.

In June 1944, west of Minsk, Nemirovskaia took part in an infantry attack and was seriously wounded. After a long stay in a military hospital, she was transferred to another division as a typist at the HQ. She ended the war on the island of Rügen in Germany.

Nemirovskaia was awarded two military orders – the Order of Glory and the Order of the Red Banner. However, the Soviet authorities refused to recognize her as a war invalid, thus refusing her the benefits and rights due to such invalids. After the war, she began working as a school teacher, but then turned to journalism. She married and had a son.

In 1990 Nemirovskaia emigrated, settling in Tel Aviv. She died in 2014.

From an interview given in Tel Aviv in 2008 by Dora Nemirovskaia

In an interview, given in Tel Aviv in 2008, Nemirovskaia recollected a terrible day in Moscow – October 16, 1941. In mid-October, the Wehrmacht came the closest it would to Moscow (in fact, the German troops reached the outer suburbs of the capital), and panic ensued in the city. In the morning of October 16, despite having a fever, Nemirovskaia went to her factory. She described what she saw there:

"I arrived and there was a huge crowd there, a huge one. The factory was closed and no one was allowed in. […] The Germans were close and people knew that the Germans were about to enter [the city]. They were screaming and yelling, - it was horrible. And they were crying 'All this is because of the Yids. The Yids are to blame. The Yids stole everything from us.' They forgot that it was the Germans [who started the war] and that the Jews had nothing to do with this. You understand that all their anger was being poured out on those who were close at hand, you see. 'It is because of the Yids. The Yids stole!' This was the case even though our boss, the head of our department, was a Jew, Lifshits, a very good-hearted man […] And they were yelling: 'Lifshits stole everything and then ran off with his [mistress]. I was standing in the middle of the crowd and feeling sick – not because of my fever, but because of what I was hearing, you understand. And I was thinking that – these bastards were worse than the fascists [i.e. Nazis]. [I asked myself] Whom should be more afraid of – them or the fascists? […] And then Lifshits came out. They had been yelling that he had run off, and he came out to them. I left and so I don't know how all of this ended".

From: An interview taken for the Blavatnik Archive Foundation in 2008 in Tel Aviv.