Hirsh Rolnik (in Lithuanian Rolnikas) was born in 1898 in Plunge, Lithuania. He studied first in a heder and then completed high school. Next he studied at the faculty of law at the University of Berlin and later completed a doctoral dissertation by correspondence.

However, when he returned to Lithuania, he could not find work in his field because that would have required certification that he had graduated from the faculty of law of the University of Kaunas. He decided to study for the qualifying examination as an external student, meanwhile working (for three years) as director of the Jewish high school in Raseiniai. In 1940 and 1941 Rolnik participated in the drafting of the constitution of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic.

At the very beginning of the war between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union he became separated from his family in Vilnius - his wife Taybe and their four children - and escaped eastward with the retreating Red Army. His family remained in the Vilnius ghetto.

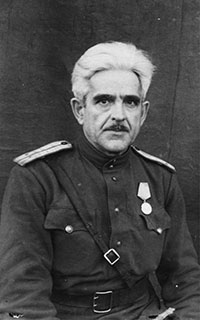

Rolnik attempted to volunteer for combat but he was rejected by the recruiting office, which was suspicious of people who had left the territories which had been annexed by the USSR in 1939 or 1940. However, in January 1943, when the 16th Lithuanian Division was formed as part of the Red Army, he was accepted and sent to the front. Rolnik served as a translator from German. On his own initiative, with the agreement of his superiors, at night he would sneak up to German positions and conduct Soviet propaganda in German. Some of the materials captured from the Germans and translated by Rolnik were used for anti-Nazi propaganda by the Sovinformbiuro (Soviet News Agency), Ilya Ehrenburg and the Lithuanian poet Justinas Marcinkevičius. In November 1943 Rolnik was award the medal for Battle Merit.

As was the case with the majority of Jews in the Red Army, Rolnik knew about the Nazi mass murder of Jews. He had no doubt that his wife and children had perished at their hands. In fact two daughters Mira and Masha survived. Mira was hidden by Lithuanians who knew her family; they were later recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem. Masha emerged alive after being in camps in Strassenhof and Stutthof. In 1963 Masha Rolnikaite published her diary of the Vilnius ghetto I Must Tell, which her mother had insisted that she memorize. Rolnik's wife and two youngest children were killed at Ponary. While the war was still raging, Hirsh learned that his brother Michel Rolnikas, a well known French lawyer and member of the French resistance had been executed by the Germans. (This took place on October 22, 1941.)

During the war Hirsh Rolnik wrote several texts devoted to the mass murder of Jews and sent them to the Jewish Anti-fascist Committee. In 1943, 8 months before the liberation of Vitebsk, he recorded detailed testimony of the non-Jew Anna Sholokhova about the annihilation of the Jewish population of the city.

In 1944 the government of the Lithuanian Soviet Republic took Rolnik from his army work to be the head of the legal group of the Republic's Council of People's Commissars and head of the Lithuanian department of the Correspondence Legal Institute. However, in 1951, due to antisemitism Rolnik moved to Klaipeda, where he worked as a lawyer until his death in 1973.

Article by Hirsh Rolnik

In November 1943 Lieutenant Hirsh Rolnikas compiled a text about the rescue of the Jewess Tisa Velikina and her rescuer Anna Sholokhova and recorded the testimony of Sholokhova about the murder of the Jews of Vitebsk. Despite efforts on his part to make the text fit within Soviet ideological parameters, it still did not correspond with the requirements of Soviet propaganda. The account made clear that the Jews were subjected by the Nazis to specific genocidal persecution rather than being killed simply as Soviet citizens. Furthermore, the very fact that the saving of one Jewish woman had to concealed from people nearby indicated that the official Soviet slogan about the "friendship of the Soviet peoples" was far from reality.

The text of Rolnikas also reveals the concern of Jews in the Red Army about the fate of their dear ones who had been overtaken by the German occupation. His meeting with the survivor Tisa Velikina had given Rolnikas the hope that some of his dear ones had succeeded in surviving.

As he wrote:

"With my military unit I traversed many hundreds of kilometers of the Soviet land that had been liberated from the German occupiers but to this day I have not met a single Jewish person who had survived the German occupation. Today, November 23, 1943, in a village in Belorussia I encountered the civilian Tisa Markovna Velikina, age 47, who had lived for two and a half years with false identity papers in areas occupied by the Germans…. She had no information about the fate of her dear ones, her parents, five sisters, and three brothers and their families or about the fate of her husband. Her two young sons survived with her there, but she was now alone: her 12 year old son had been killed by a German grenade while the older one, 17, was with a partisan unit. Her life (if one can call it a life) for two and a half years had a chain of unbelievable deprivation and suffering. She was continually in great danger. For whole months she spent the day lying under a bed or in an attic and the night on a stove, rushing to hide in the bushes or trying to sleep in some ravine. On many occasions Velikina attempted to end her life of suffering by committing suicide. However, she was encouraged and not allowed to give up by the Russian woman Anna Timofeevna Sholokhova, whom the Jewess she saved only knew as 'Nikolaevna.' At the very worst times Sholokhova encouraged Velikina by assuring her that the Red Army would still arrive and save her and all others persecuted by the Hitlerites. While some of the people from whom she sought help met Velikina with meanness and baseness, from others she experienced care and a readiness for self-sacrifice.

From the first days of the occupation the Germans threatened with capital punishment those who sheltered or aided Jews in other ways. There were cases when such benefactors were killed alongside the Jews they had helped.

The above-mentioned A. T. Sholokhova witnessed incredible abuse of Jews, including seeing with her own eyes the shooting of the Jews of Vitebsk…. [The follows a detailed account of the murder of the Jews of Vitebsk]."

From: GARF 8114-1-161, copy YVA JM/26142.