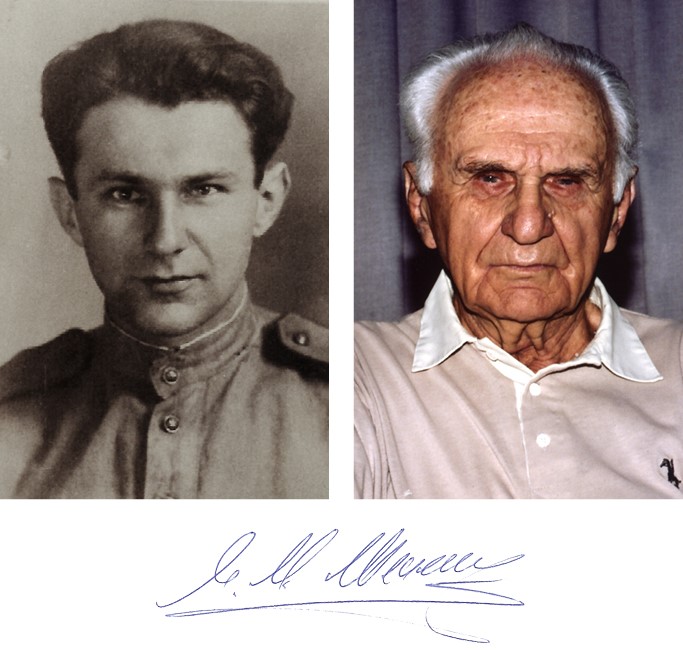

Iakov Shepetinskii was born in 1920 in Slonim, a town that in 1921, following the Polish-Soviet war, was ceded to Poland (it is now in Belarus). In September 1939, the area was conquered by the Red Army and annexed to the Soviet Union; it was incorporated into the Belorussian SSR (Soviet Republic) as "West Belorussia". When the German army invaded the Soviet Union, Iakov was working in Bialystok. He quickly returned to Slonim, to his family, but it was too late for them to flee. On June 24 the Germans entered Slonim and within a short time Shepetinskii's family was imprisoned in the ghetto there.

In November 1941, the Germans shot to death 8,000 Jews in Slonim on one day. Shepetinskii was one of the only 10 survivors. He fell into the common grave, but managed to run away after nightfall.

In June 1942, during another German murder operation, Iakov, his parents, three of his brothers (including five-year old Uri), and his sister escaped from the ghetto to a nearby forest. Three Shepetinskii siblings joined the Soviet Shchors partisan unit headed by Pavel Proniagin. They joined the Proniagin's 51st company, which consisted of Jews. Iakov's parents and two younger brothers became part of the family camp. Iakov took part in many anti-Nazi operations, while his sister Raia served as a nurse. The rest of his family perished: his brother Herzl – in combat, his parents and his younger brothers – in the family camp.

In July 1944, the vicinity where was Shepetinskii fighting was liberated by the Red Army. Shepetinskii took part in the parade of the partisans in Pinsk, and then was immediately drafted into the Red Army, in which he became a soldier of the 61st Army on the 1st Belorussian Front. During his military training in West Belorussia he learned of the death of his parents and siblings in the partisan family camp. When he visited Slonim, he found that this Jewish shtetl did not exist any more – neither its houses nor its people.

In September 1944, his 61st Army was transferred to Latvia. Shepetinskii took part in the capture of Riga, and then he was transferred to Poland. He fought in northern Poland, and then in Germany, in May 1945, he was wounded and ended the war in a hospital near Berlin. In his postwar memoirs, Shepetinskii wrote:

"I am meeting May 9 – Victory Day – in a hospital. Everyone is having fun, triumphing, hugging, kissing. [For them] the war is over. Home to their family, to their loved ones, but I am lying with my face in my pillow. I am crying. I have no home, no family, no relatives, no friends. I am alone.

Amidst this general triumph of joy, well-deserved happiness, and hope, you feel broken, suddenly realizing the depth of the tragedy, both your own personal one and that of the whole Jewish people."[1]

After the war, Shepetinskii remained in Berlin as a military translator. He was reunited with his sister Raia. He also met some of his former partisan comrades, who suggested that he desert from the Red Army and to move with them to Palestine, but he refused. However, in his capacity as translator, he had a number of opportunities to cross the new German-Polish border at Frankfurt-an-der-Oder. Almost every time he returned, he gave rides in his truck to Jewish survivors who were eager to leave Poland to reach either the Land of Israel or North America.

In April 1946, Iakov was arrested by the counter-espionage organs of the Red Army and charged with spying for the British intelligence service. Two comrades, both Jewish were arrested with him on the same charge. Shepetinskii was urged to cooperate with the investigators, but after his decisive refusal, he was court martialed. He was sentenced to ten years in the GULAG and sent to serve his term in the Soviet sub-Arctic.

Shepetinskii was released in 1954. In 1966, he left the USSR for Israel. In 1969, he was called upon to travel to Hamburg to identify the former Gebietskommissar of Slonim Gerhard Erren.

In 1946, the military translator Iakov Shepetinskii killed a captured German Nazi who stated in his presence that it had been right to kill Jewish children

"Somewhere in early March 1946, our punitive organs detained a German who had been sent to work for ten days dismantling a factory. During that time [the Soviets] wanted to recruit him [as an agent for the secret police]. To my misfortune, Senior Lieutenant Andriyanov was one of the [Soviet] interrogators (a cruel one!), and I was his translator. The middle-aged German was a Nazi with experience who had worked in the propaganda apparatus of Goebbels. Interrogation being what it is, there was not much time: everything was done to break him, to scare him to death so that as soon as he was asked to cooperate, he would grasp at the offer with both hands.

[…] He [the German] took me for a German from the Volga region. […] Once during a break, when the interrogator left us alone, I started talking about Jewish matters.

'Listen' – I said to him. 'I can, perhaps, understand that you treated Jews so cruelly out of hatred. But, why did you destroy babies, infants? After all, these little ones had just been born, what were they guilty of?'

He interrupted me and, pedantically, began to explain:

'You don't understand anything. Such babies pose the greatest danger to our Aryan race. There are those among them, especially the girls, who do not differ from our children outwardly. But if a boy does not undergo a circumcision ceremony and if, somehow, such a child gets into an Aryan family, he pollutes our race!'

During his explanation, I lost control of myself. Before my eyes I saw my younger brother Uri. Involuntarily my hand opened the drawer of the desk and grasped the cold metal of a pistol ... – a shot rang out and he [the German] fell to the floor. Andriyanov ran into the office:

'What have you done? You have ruined everything!'

I was dumb, I could not utter a word. He [Andriyanov] quickly took the heavy paperweight off the table and threw it through the window into the yard.

'Say that he threw this at you" – and he ran out."

[Iakov Shepetinskii, Prigovor, Tel-Aviv, 2002, p. 88-89]

[1] Iakov Shepetinskii, Prigovor, Tel-Aviv, 2002, p. 85