Leonid Rabinovich (pen name - Leonid Volynskii) was born in 1913 in Odessa, Ukraine. After completing school in Zhitomir, he attended the Kiev Art Institute. After graduating, he became an artist at the Theater of Opera and Ballet in Kiev and in the mid-1930s he was a main painter of the Ukrainian State Jewish Theater in the same city.

Rabinovich headed for the front as a volunteer on June 23, 1941. In September of that year, when his unit was surrounded, he was taken prisoner. After successfully escaping from the POW camp, Rabinovich returned to the front and worked at camouflaging forces of the First and Second Ukrainian Fronts.

At the beginning of May 1945, when he was serving in the 5th Guards Army a special group was established to search for cultural treasures that had been hidden in the Reich. This group was headed by Junior Lieutenant Rabinovich. On May 9 in a tunnel under Zwinger (the museum district of Dresden) he found a map with special markings. These marks indicated the location of 53 treasure troves or caches, where the Germans had hidden paintings and other items from the connections of museums and galleries in Dresden.

Rabinovich described one of his finds in his memoirs:

"Behind a cart in the humid darkness of mines in wooden containers there were paintings of the Dutch school from gallery collections… I don't know what would have become of these treasures if we had not found them in time…. For some time these pictures had suffered from terrible humidity in the cold underground. That alone could well have destroyed them."

In the brief period between May 9th and 28th Rabinovich's group uncovered all of the caches, where they found the majority of the paintings from the Dresden art gallery, including Raphael's Sistine Madonna and Rembrandt's Portrait of Saskia, collections of coins, and pieces of porcelain, and many other extremely precious items of immense artistic and scientific value.

After the war Rabinovich returned to Kiev, where he learned that all the members of his family except for his wife and a daughter had been killed in the fall of 1941 at Babi Yar.

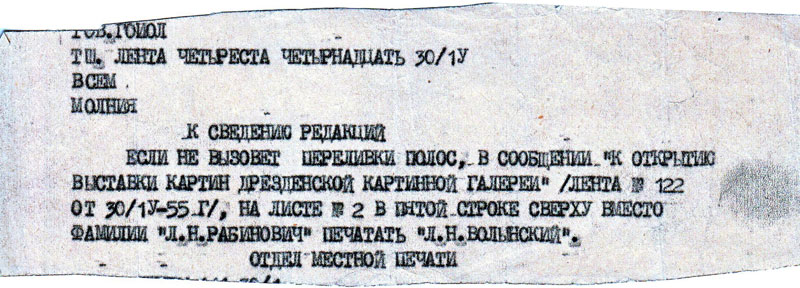

In April 1955 the main Soviet newspaper Pravda prepared to publish an article about an exhibition of masterpieces of art that was about to open in Moscow. The Soviet authorities had decided to hand over the collection to the German Democratic Republic, admitting that the collection had been taken covertly at the end of the war. Rabinovich was going to be cited as the person who had saved the masterpieces of the gallery. At the last moment the authorities demanded that he change his name to a non-Jewish one; as a result he chose the name Volynskii. Then an urgent telegram was sent from Moscow to local editors who had already received a notice about the exhibition: "For the information of the editors. If this won't cause a change in the layout, in your notice 'about the opening of an exhibition of paintings from the Dresden Art Gallery' [sent to you as telegram No. 122 on April 30, 1955], on page 2 line 5 from the top, instead of the name 'L.N. Rabinovich,' insert 'L.N. Volynskii.' [Signed by] the Department for the Local Press."

From that time until the end of his life, under the pen name Leonid Volynskii, Rabinovich produced literary works, mainly popular books about artists.

In 1966, together with the non-Jewish writer Victor Nekrasov and others, Rabinovich was one of the participants in the unsanctioned meeting held to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the mass execution of Jews at Babi Yar.

Leonid Rabinovich (Volynskii) died in Moscow in 1969.

Leonid Rabinovich's Memoir

In his book Skvoz' noch' (Through the Night) Leonid Rabinovich (Volynskii) described his exceptional survival as a Jewish POW:

As a Jew, his survival was extremely exceptional. He related this story many years later in his book Through the Night:

"I exchanged a glance with him [a German officer] and then there took place what can be explained by no other word than 'fate.' He asked, 'What are you standing here for?' I shrugged my shoulders without saying anything. He asked, 'Are you a commissar?' I shook my head 'No.' That was true. I was hardly going to lie in regard to the next question [as a rule, the next question addressed to POWs was whether they were Jews]. But he didn't ask anything else. Evidently, my appearance did not at all correspond to his image of those who were supposed to be killed. For a fraction of a second everything hung on a thread; he then turned to a subordinate officer and said something to him quickly in a very concise way and then shouted to me 'Weg' (Get out of here). 'You're crawling in where you don't belong…!'"

Leonid Volynskii, Skvoz' noch' (Through the Night), Moscow, 2005.