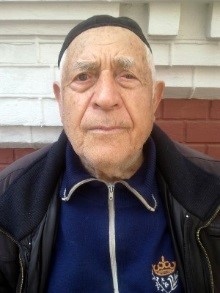

Leonid Shmurak was born as Leibe Shmurak in 1927 in Novograd-Volynskii (in Ukraine). The town was known in the Jewish world as Zhvil. According to Shmurak,1 his maternal grandfather Moishe was one of the richest men in town and before the revolution had financed the construction of a synagogue. After the revolution Leonid's family lived more modestly, but not in poverty. His father, also named Moishe, was a foreman of a group of bricklayers. The family was religious and his father used to take Leonid with him to synagogue. Although the family spoke Yiddish, his parents sent Leonid to a Ukrainian-language school. Leonid finished only five years of schooling and then began working on a nearby kolkhoz.

With the beginning of the Soviet-German war in June 1941, Leonid's father decided to try to save his family. Moishe's elder brothers refused to leave and later, under German occupation, all of them perished with their families. In toto more than 80 of Shmurak's relatives died at the hands of the Germans. Moishe Shmurak and his family – Leonid's mother and four siblings – arrived safely in Soviet Central Asia, where Leonid went to work on a cotton-growing kolkhoz. After the liberation of Novograd-Volynskii by the Red Army in 1944, the family returned to their native town. Some people immediately approached Leonid's father and said: "Moshko, your brothers and their families lie [dead] at the house of Hersh [father's eldest brother]." Moishe took Leonid, hired several non-Jews, and went to exhume the bodies of his relatives. The horrific picture of the exhumation greatly affected Leonid. After the exhumation, he went to a recruitment office and volunteered for the Red Army. Despite being only 17 years, he was drafted. Before his departure to his unit, Leonid received a kamea (religious amulet), a one kopeck coin, from a local tsaddik. Leonid believed that he survived the war due to this amulet.

Leonid was assigned to the 12th Guards Infantry Division. His military training was short – only two months – but intensive. After this training, he was sent to Poland, where he participated in the recapture of Warsaw. His weapon was a SVT rifle ("Sveta" in Red Army slang) with a bayonet, and his "specialty" was bayonet fighting. In his interview Leonid Shmurak made the following admission:

"I never took a German prisoner. I took revenge. Sometimes it happened that he raised his hands and I still shot him. The commander asked: 'Why do you do this if he surrenders.' I reply, 'They killed most of all'."

Ibid

After Warsaw, Shmurak took part in the storming of Breslau, then he fought in Poznań and in Berlin, where he was wounded, but not seriously.

Shmurak's highest rank at the end of the war was sergeant-major (starshina). He was awarded several medals during the war but he received the order of the Patriotic War, 2nd Class only after the war.

Leonid Shmurak was demobilized only in 1951. He settled in Kiev and worked at a military metal-working plant. Shmurak married and had two sons. He retired in the mid-1990s and was an active member of the Kiev synagogue. He died in 2017.

Additional information

The terrible exhumation of the bodies of Leonid Shmurak's relatives in 1944 – a total of eighty people – and its great effect on him.

"When we arrived in Novograd, some people approached my father and said:'Moshko, your brothers and their families lie at Hersh's [father's eldest brother] house'. Uncle Herschel had a farmstead, and it was there that the Germans killed our relatives. Well, Dad took me and hired a few goyim. We arrived and began to dig up and transfer the bodies to the Jewish cemetery, that's all. And when the Germans buried them … there were little children there, with their children's clothes ... I saw it all, I could not stand it, I rushed to the military enlistment office and said: 'I want to kill Germans.' And the colonel said to me: "Bring your birth certificate." I ran and brought the certificate. He looked and said: 'Go home. You are only seventeen years old. Go play soccer!' I said to him: 'I won't play soccer. I want to kill.' I spent the night near the military commissariat and stayed there for two days. […] I did not leave. On the third day, the colonel summoned a major and said: 'We need such lads.' So, they took me into the army. I was tall – a meter and seventy centimeters or more. And they were taking just such strong men into the guards units.

[…]

Listen, [there, in Germany] I met one fellow – he was a Jew, but he had himself registered as a German. He told me how the Jews were tormented in Germany. Very few of them had survived. I helped him - gave him some food and some things."

From the interview taken in 2014