Lev Aronshtam was born in 1921 in Belorussia. Several months later, his father died. In 1926 is mother married a widower with four children. Lev's stepfather was a minor NEPman (a person who, during the so-called New Economic Policy [abbreviated NEP] of 1921-1929, began a private business). In 1928, anticipating that the NEP would soon come to an end, Lev's stepfather moved to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). However, as a former NEPman, he was arrested, albeit for a short time.

In 1939 Aronshtam graduated from high school and entered the Leningrad Institute of Chemistry and Technology (now St. Petersburg State University of Technology). In 1940, he was summoned to a recruitment office. There he was asked whether he was willing to "volunteer" to attend a military school that would train him for a military profession that was similar to the civilian one he would have had if he graduated from the Institute. Lev attempted to reply in a diplomatic manner, saying "If the Motherland so requires…" The recruiting officer interrupted to say "That is just what the Motherland requires!" and he registered Aronshtam for the Kalinin Military College of Chemical Defense.

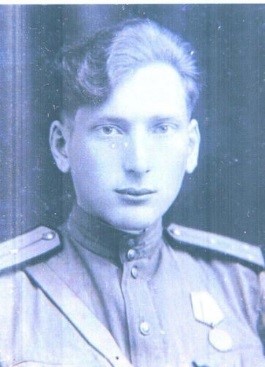

With the beginning of the Soviet-German War in June 1941, the cadets received the rank of lieutenant and were sent to the front. Aronshtam's 298th Rifle Division was deployed on the Briansk Front in Belorussia, and then in the western part of Russia. This division was supposed to defend the city of Oriol, but it failed to do so. In October 1941, Oriol was captured by the Germans. At that time, Aronshtam saw German planes raining masses of leaflets on the heads of the soldiers of the retreating Red Army and witnessed the impact that the leaflets had on the soldiers. The main message of these leaflets was "Kill the commissars and the Jews, and surrender." Hundreds of soldiers -- belonging to many different ethnic groups of the Soviet population except, of course, the Jews -- did indeed surrender to the enemy. After the war, Aronshtam stated (with some exaggeration) that its Jewish soldiers and officers were an element that held the Red Army together during the retreat of 1941. His own regiment was encircled by the enemy in October 1941. For several weeks the remnants of the regiment attempted to break out of the encirclement – avoiding villages (since no one knew what the attitudes of the Russian peasants to the Red Army were) – sometimes fighting against the Germans. When a group of 20-25 men broke out of the encirclement to the Soviet side, it included only political commissars, officers, and Jewish soldiers. Because he kept his military papers during the breakout, Aronshtam, was not sent to a punishment battalion but, after a short rest, was assigned to the defense of Moscow.

In the winter of 1942, Aronshtam was sent to an anti-tank artillery school and, upon graduating from a short course there, was sent to fight against the German tank army of Guderian. In the summer of 1942, his 5th Anti-tank Brigade was transferred to the area of Stalingrad. At this time, the senior lieutenant Aronshtam served as an aide to the chief of staff of the Brigade – a circumstance that probably saved his life during this operation. When the Stalingrad operation ended successfully, Aronshtam was promoted to the rank of captain and received a furlough. During this time, he succeeded in finding and visiting his mother in Soviet Central Asia, to which some members of his family had been evacuated. There he learned that his stepfather and sister had perished – they were evacuated to an area in the North Caucasus that was later captured by the Germans and they shared the fate of the other Jews there.

In 1943-1944, Captain Aronshtam fought in Eastern Ukraine, then in Belorussia and in Poland. In the winter of 1945 his regiment passed through the (already liberated) Auschwitz (the site he described was probably a labor sub-camp of Auschwitz). In the interview that he gave in 2006 or 2007, he said:

"People there who looked like ghosts could not believe that we were Russians. It is true that they had seen the Red Army in 1939, but then there were no people with shoulder straps in it. They believed me only when I turned to them in Yiddish. No speech can convey our feelings. I felt very deeply Jewish. I knew about Kristallnacht and I knew that the Germans were shooting Jews, but that ... Perhaps something had been written before in our newspapers, but we did not believe it. We thought it was propaganda. Even in Ehrenburg's reports about the mass extermination of Jews by the Germans, you had to read between the lines. We had no time to read between the lines ... I believed it when I saw it with my own eyes, when I saw rows of sacks stuffed with human hair, when I heard the stories of Jewish prisoners who had survived. When I saw the crematoriums...."[1]

VE-Day found Aronshtam on the island of Rügen in Germany. However, the war did not end for him on that day. In the summer of 1945, he was sent to Western Ukraine to fight against Stepan Bandera's guerillas – the so-called Ukrainian Insurgent Army, which was fighting for an independent Ukraine. On the basis of his experience at that time, Aronshtam denied that the Bandera's warfare had an anti-Jewish character.[2]

Lev Aronshtam was demobilized in 1946. While he was in Western Ukraine, he married Esther, a Polish-Jewish refugee. With her, he settled in Eastern Ukraine, where he worked as a geologist. His experience then of antisemitism on the part of Soviet officials disabused him of some of his illusions. "When I was fighting on the frontlines, I felt that I had a mother-country, but now I feel that I do not have one," Aronshtam stated in an interview. As the husband of a former Polish citizen, in 1959 he "repatriated" to Poland, where he settled in Wroclaw and learned Polish. However, Communist Poland also proved to be antisemitic. In 1968 Lev and Esther left Poland for Melbourne, Australia, where Esther's brother was living. Since then, Lev, his children, and his grandchildren have been living in Australia. Esther died there in 1996. In Melbourne Lev maintains contacts with Jews from Poland, with whom he speaks either in Yiddish or in Polish.