Moisei (Moyshe) Teif was born in 1904 in Minsk. His father Solomon was an assistant in a medical equipment shop. Under the Soviet regime, he became a worker. Despite Solomon's original bourgeois profession, the family lived in a poor quarter of Minsk. In 1905, during the First Russian Revolution, one-year old Moyshe narrowly escaped being killed by Cossacks: during the so-called "Kurlov shooting" at a revolutionary meeting, his mother Revekka unfortunately was standing in the way of the crowd that was fleeing from the meeting. In the turmoil, she dropped the child. Since the Cossacks' horses jumped over him, the child survived. After World War II, Teif described this event in his story "Alpinezl" (roughly "a survivor by miracle", from the Hebrew words al-pi nes, "by a miracle"). Young Moyshe studied in a heder, but failed to finish it. At the age of 13, he began working at a wall-paper factory. His first Yiddish-language poems were published in 1920 and three years later he joined a group of young Yiddish poets associated with the newspaper Der yunger arbeter. His earlier poetry had a romantic character. In the mid-1920s Teif settled in Moscow, where he was a member of the editorial staff of the newspaper Eynikayt. In 1933, he graduated from the Yiddish department of the faculty of literature of the 2nd Moscow State University. In the 1930s, he began to write prose and undertook translations into Yiddish (for example, he published translations of Ivanhoe by Walter Scott and The Legend of Thyl Ulenspiegel by Charles De Coster). Many of his other translations remained unpublished.

In 1938, Teif was arrested as an alleged member of a "Jewish nationalist spy organization" and sent to the GULAG . In April 1941, he was unexpectedly released from the camp, but denied the right to live in large cities. Teif settled in Borisov, 100 kilometers east of Minsk. It was here that he met the beginning of the Soviet-German war. Teif succeeded to escaping eastward, but left behind his small son in Minsk with his mother. Both of them subsequently perished in the Minsk ghetto. The image of a little boy recurs in Teif's poetry after this time.

In October 1941 Teif was drafted into the Red Army. His first service was with a battalion for aerial observation and communications that was deployed in the Saratov Region far from the frontline. From March 1942 to the fall of 1944 former political prisoner Moisei Teif surprisingly served as the librarian of the political department of the 57th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Division, which was defending Moscow from enemy air raids. From the fall of 1944 to his demobilization in September 1945 he served with the Choral and Dance Ensemble of the Western Front of the Anti-Aircraft Defense. Such a non-combat role greatly upset Teif, who wanted to fight like a "real soldier" (see Appendix)."

After the war, Teif was awarded two medals: "For Valiant Labor during the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" and "For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945."

In 1951, during Stalin's campaign against the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (with which he worked after the war) Teif was arrested again. The attempts of the MGB (the precursor of the KGB) to accuse him of espionage were unsuccessful. When Teif refused to sign the protocols of the interrogation against him, the MGB changed the charge against him to "Jewish nationalism". Teif was sentenced to 8 years in "corrective camp." There he continued to write Yiddish poems which after his release he signed with the penname Shaye Sibirskii (Shaye of Siberia).

After Stalin's death in 1953 and 1954 Teif's sister Motlia began her appeals of her brother's conviction. These appeals were unsuccessful (the second appeal, in particular, was rejected on the grounds that his literary works were nationalistic and, therefore, his conviction and sentence had been justified). However, after a third appeal in 1955, Teif was freed and rehabilitated.

After his liberation in 1956, Teif continued to write poetry. The Holocaust was a major theme in these works. Examples were "Kikhelekh un zemelekh," "Ana Frank" and "Zeks milyen {Six Million}", and "Sonye Madeysker." Some of his poems were translated into Russian by leading translators. The author of the introductory note to the spring 2004 issue of the Russian-language Jewish journal "Korni," which commemorated the 100th anniversary of Teif's birth, wrote that Teif was probably the Yiddish poet of the postwar generation who was best known to the Russian public. Teif began to translate the Biblical Song of Songs into Yiddish. Moisei Teif died in 1966.

Additional Information

Teif's letter to Shmuel Halkin

Teif was bothered by the fact that during the whole Soviet-German war he served not as a real soldier on the frontlines, but was engaged in non-combatant service in the rear, in safe places. In December 1944, Teif wrote the following letter to Shmuel Halkin, a member of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee:

"Dear Shmuel!

You know how greatly I have suffered for almost 7 years. I kept silent. I did not say anything. But now I have to turn to you. I had hoped to be a military officer but, quite by chance, my superiors took a liking to me, and did me a favor. They assigned me to serve in a political department. In fact, I continue to be a soldier. I will [i.e., hope at another time to] have the opportunity to tell you in detail how it happened that my dream of becoming a combat officer failed to be realized due to unexpected causes. Right now, it is very hard, even abhorrent, for me to be here, so I am turning to you with a request. You must do all you can to have me relieve of my work at Eynikayt. It should be easy to release me for the following reasons: first of all, I am not an officer; second, I am not a professional politician; third, I am a sergeant; fourth, my headquarters remains in Moscow […]

I beg you. Help me! Speak with [Itzik] Fefer […]

Yours, Moishe Teif".

Liia Dolzhanskaia, who published this letter in the issue 27(2005) of the journal "Korni". believed that Teif sent this letter in the hope that he would be sent to the front as a military correspondent/ However, the letter was used by the MGB against Teif when he was arrested in 1951.

Teif's poem "Kikhelekh un zemelekh" (Cookies and Rolls) presents one example.

As noted above, the image of his only child, his son, who perished in the Minsk ghetto, recurs in Teif's poetry. His poem "Kikhelekh un zemelekh" (Cookies and Rolls) presents one example:

"…

Where are you, my boy?

Where are you, my dear one?

It seems that you are shouting to me,

From the burning ghetto …"

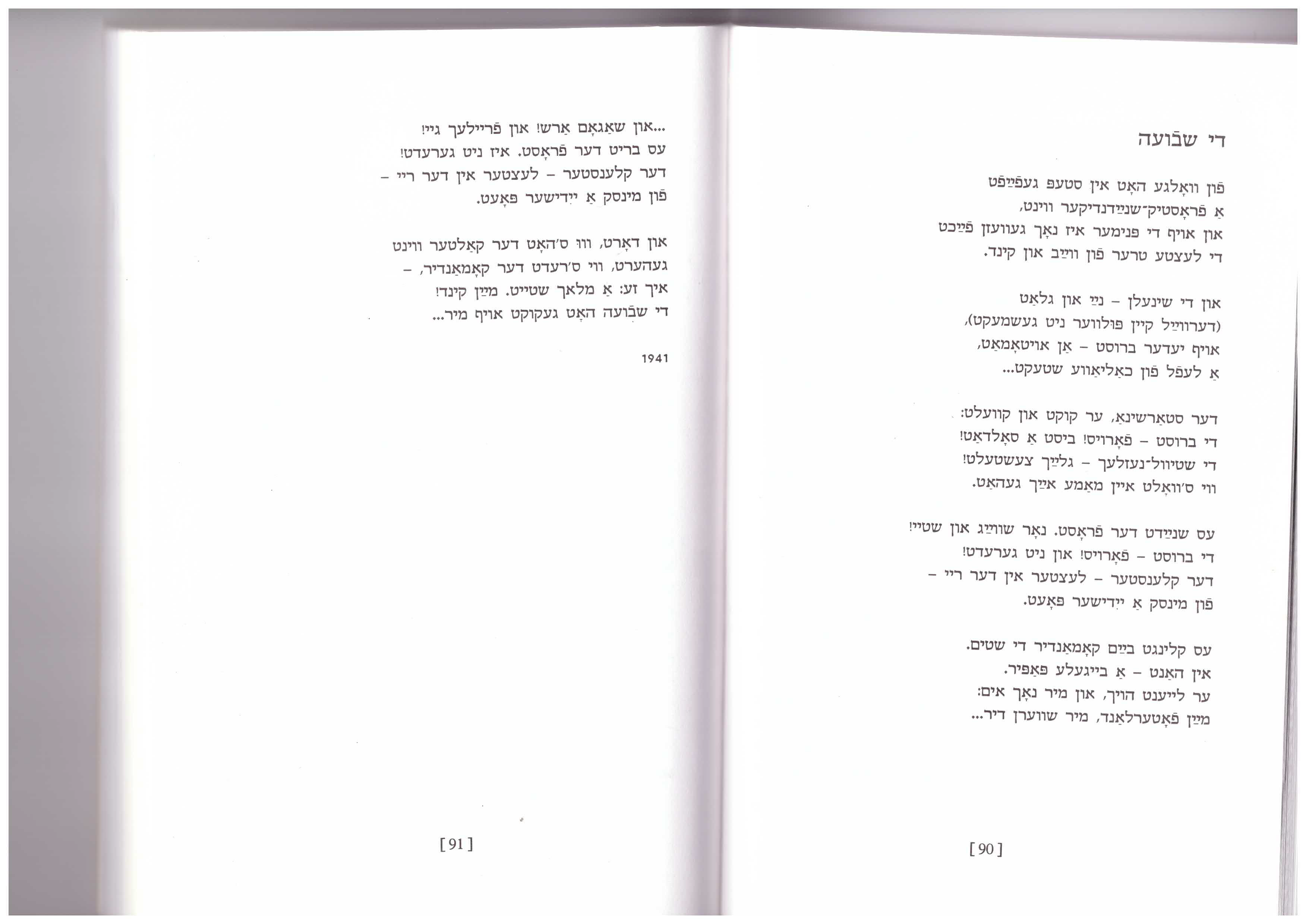

In "Di Shvue" (The Oath) the poet wrote about how his dead son appeared before him when he was taking his military oath:

"… The commander's voice rings out.

He is holding a piece of paper in his hand.

He reads aloud and we repeat after him:

'My Motherland, we swear to you…'

[…]

And there, where the cold wind

Is blowing, and from where commander's words are heard –

I see an angel standing. It is my child!

The oath is looking at me…"