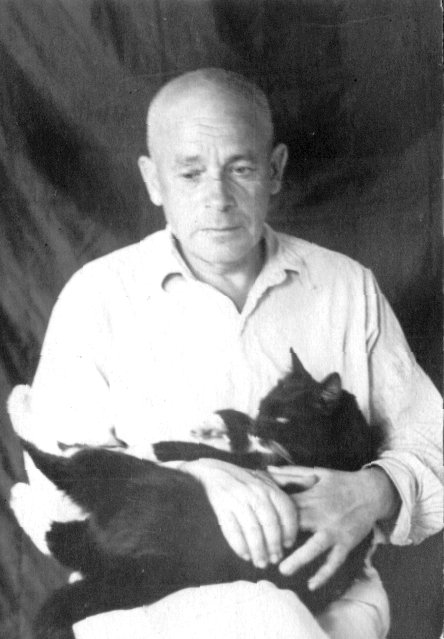

Semyon Gekht (Gecht), a famous writer and journalist, was born in Odessa in 1901. He was originally named Abraham, but later acquired a second name – Semyon, or Shulim. As Gekht would later explain: "<…> According to old Jewish tradition, if a child fell ill, the parents would give them an additional name. That is why I have had two names since my childhood" 1. A child with such a name was not recorded in the birth registry of the Odessa Rabbinate, and that is why there are different versions of Gekht's date and place of birth.

Gekht's parents, Gersh and Lea, died very early (according to one account, they perished in a pogrom), and Semyon was brought up in the family of his elder brother. After finishing the 2nd Jewish School of Odessa, he worked as a folder in the print shop of the Odesskie Novosti ("Odessa News") newspaper, and later as a typesetter. In 1920-21, he even earned money as a gardener. Semyon Gekht made his literary debut very early, as a poet. At the age of twelve, he wrote a poem and sent it to the Detstvo i Yunoshestvo ("Childhood and Adolescence") magazine, which decided to publish it. Following this success, poems by him began to appear in other magazines. After a lengthy hiatus caused by the hardships of World War I and the Russian Revolution, he resumed his literary activities in 1922, with a new poem titled "Deviatoe Yanvaria"("January 9," the day of the massacre of a workers' demonstration in St. Petersburg in 1905), which appeared in an Odessa newspaper. At the end of that year, he was introduced to Eduard Bagritsky (a successful poet based in Odessa), and joined a literary circle in that city. There, he met the famous writer Isaac Babel (author of the brilliant Odesskie Rasskazy ("Odessa Stories") and Konarmia ("Red Cavalry")). According to contemporaries, Gekht imitated Babel's style and was influenced by him.

In 1923, Gekht moved to Moscow. By that time, he had already stopped writing poetry, and now presented himself as a prose writer. In 1925, Gekht's first book, Stories, came out in Moscow, and it was followed by ten volumes of short stories and essays, as well as two novels, over the next fifteen years. In addition, Gekht worked as a translator from Yiddish. His translations include several short story collections by Sholem Aleichem and other Yiddish writers. He also wrote articles on the work of Sholem Aleichem and its cultural significance. In his writing, Gekht carried on the tradition of Russian-language Jewish literature. The primary subject matter of his books from the 1920s and 1930s was the life of Jews during the Russian Revolution and in the subsequent years. Gekht's first major novel is The Man Who Forgot His Life, about the tragedy of the Jewish shtetl during the Russian Civil War. The major problems facing the Jewish people – antisemitism, poverty, the lack of any prospects for the future, permanent humiliation, and violence – were addressed in this novel.

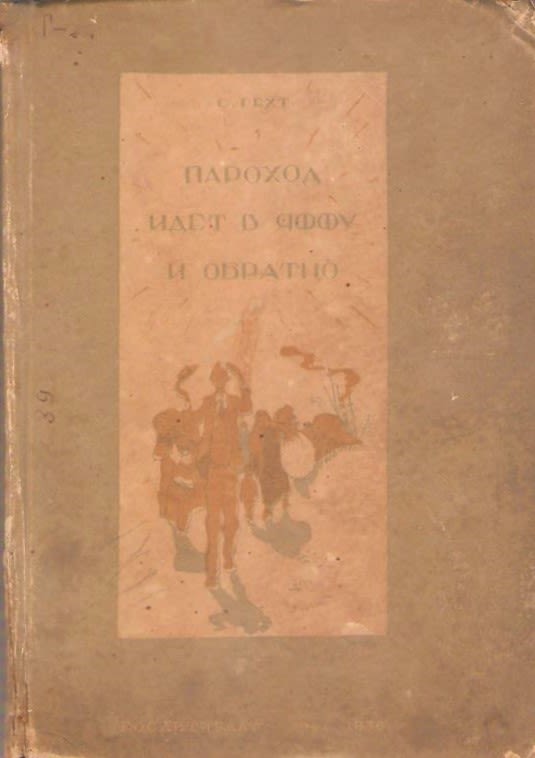

The new reality of the young Soviet state became the focus of Gekht's most famous novel, Parokhod idet v Iaffu i obratno ("The Steamer Goes to Jaffa and Back"). This book tackled the official Soviet policy vis-à-vis the Jews and described their mass resettlement to Birobidzhan. Gekht underscored the importance of the Birobidzhan project by juxtaposing it with the Zionist one. He explored this theme through the life story of his protagonist, a Jew named Gordon, who decides to move to Palestine. The most vivid passages in the novel describe Gordon's childhood and youth in Odessa, his self-perception as a Jew, his voyage to Palestine, and his first steps in his new homeland. Gekht gives a relatively neutral portrayal of Mandatory Palestine, the bloody clashes with the Arabs, and the passionate speeches by the Zionists; he even cites a poem by Vladimir (Zeev) Jabotinsky. For this reason, Gekht was denounced in the Soviet press, with some critics going so far as to accuse him of "covert Zionism." Later, in an attempt to exculpate himself, he wrote: "The whole world stands in awe of the fact that the Soviet regime has so easily, in one fell swoop, resolved the Jewish question once and for all" 2. Gradually, Gekht's books began to focus on the transformed life of the Jewish people in the Soviet Union.

In his writings from the 1930s, Gekht also described the atmosphere of paranoia and denunciation in contemporary Soviet society, and the fabrication of charges by the NKVD ("Together", "A Cautionary Tale"). He was one of the few writers who dared to depict what was actually going on in the country during Stalin's purges. The short story “A Cautionary Tale” (1938) addresses the fate of a young Jewish engineer who is unfairly accused of sabotage, and then acquitted. Gekht wrote about the meeting of two brothers – the protagonist, who is building a factory in Siberia, and his elder sibling, who is happy to return from Palestine and begin a new life in the USSR. Gekht also took part in an ambitious ideological project dreamed up by Stalin: writing the history of the construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal. Although the canal was built by the forced labor of Gulag inmates, and is nowadays regarded as a prime example of state violence, this project was meant to showcase the greatness of socialist construction and serve as a successful model of rehabilitating criminals. The book about the canal, which was published in 1934, was a collection of essays by different authors. Gekht contributed to the chapter titled "Named after Stalin."

From 1923, Gekht, together with other writers who had recently moved from Odessa to Moscow, worked in Gudok ("The Whistle"), the official newspaper of the Soviet railways, which emerged as a major literary outlet in the interwar period. When the Soviet-German War broke out, he became the war correspondent of Gudok, while also contributing essays to Literaturnaya Gazeta ("The Literary Gazette"), the central military newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda ("The Red Star"), and others. The protagonists of his wartime essays ("The Brothers Rotenberg", "Alone") were Jewish Red Army soldiers who performed heroic deeds, destroying superior enemy forces. After the liberation of his home city of Odessa, Gekht was one of the first native writers to return there. His essay “The Son of Odessa” appeared in Krasnaya Zvezda on April 11, 1944. In May that year, he was arrested for "anti-Soviet agitation" and sentenced to eight years in the Gulag. Gekht was released in 1952, but was banned from residing in the ten largest cities of the USSR, including Moscow and Leningrad. He chose to settle in Ryazan, where he worked as a cleaner in a public park. A few years later, after the death of Stalin in March 1953, he was allowed to return to Moscow. He resumed his writing career, publishing mostly memoirs and essays. Some of these focus on Jews whose lives have been destroyed by the war ("Nightingale Booth", "Debts of the Heart"). He died in 1963, and was buried in Moscow.

Related Resources

A fragment of the novel The Steamer Goes to Jaffa and Back

Like the Yemenite Jews, Gordon had no wish to stay in Jaffa. The gate of Jerusalem stood before him, and he was eager to pass through.

<…> Palestine still belongs to Turkey, while the land belongs to the Arabs. But the Yemenites refused to spend even a single day in Jaffa. They were impatient to get to Jerusalem, to press their lips to the greasy moss covering the Wailing Wall, the last remnant of Solomon's ancient temple.

Leaning against the body of the truck, Gordon gazed greedily at his surroundings. The white road and the gardens, which were protected by hedges of tiny, glossy greenery. White, chalky dust covered both the leaves and the dark fruit peeking through the fences. Endless orange groves stretched past. Stone fences alternated with cactus hedges. These trees looked like gorgeous monsters, with their flat leaves spread like large, dark-green platters. They were joined at the rib and studded with clumps of long, tough spines.

— It is called opuntia, — said the driver in Russian.

He noticed Gordon's look of surprise.

— I see that you don't speak Hebrew. Me neither. People here will look askance at you. And do you know Russian well?

— I do.

— Thank God! It is better to speak Russian than our "jargon" [Yiddish]: The locals dislike this language.

The driver worked for the Solel-Boneh construction company, transporting crates of glass to Jaffa. At present, he was returning to Jerusalem, where an office of his firm was located.

— I don't understand, — said the driver, — why you wish to go to that poorhouse, Jerusalem. You must be looking for work. Why would anyone look for work in Jerusalem? You would be better off staying in Jaffa. There are two hotels under construction in Tel Aviv, and extensive plumbing projects… Why would anyone go to Jerusalem?

Gordon listened to the driver and kept up his greedy scrutiny of his surroundings. Bare, reddish-yellow fields. Camels were walking by, jingling their bells. Sheep were wandering about. Guard towers came into view some distance from the road. The truck overtook a wagonful of elderly Jews. Upon hearing the horn, two Bedouins led their horses off the highway.

The road crept upward. Suddenly, the passenger beheld the gravelly mountains of Judea. The orange groves vanished, and the land became barren and desolate. Not a single tree in sight, except for the occasional shrub pushing its way from under a rock. Stony basins. The truck drove through a cactus-shrouded Arab village. The road became ever steeper, and the bare crags grew ever more sheer. The vehicle was climbing the Jerusalem plateau. It would dip into valleys, then emerge into open fields, which offered a glimpse of the blue stripe of the Mediterranean.

Semyon Gekht, The Steamer Goes to Jaffa and Back. Moscow, 1936. pp. 43-46.

A fragment from the military report "Alone", supposed to be published

Flaxerman turned back from the mill and snuck up to the house, which was the subject of the young woman's ominous muttering. With a mighty yank on its chain, a dog rushed through the yard, clanging and barking. Flaxerman lay down close to the fence and began to watch. Someone came out of the house onto the porch. Flaxerman could make out the armband. The police chief stared around for a long time. He held the door to the hut half-open, and voices talking hurriedly in German could be heard from beyond it.

-- Why the hell did he bark? – said the bewildered policeman. – There's no one here, – he added, turning to the anteroom.

He went back inside; the bolt gave a dry click.

Flaxerman went around the hut and saw three dark windows. The same hurried German voices echoed faintly from the room beyond.

-- They are conferring with the police on some matter, -- Flaxerman realized.

He stepped backward, took a deep breath, as though doing calisthenics, and threw the grenade.

Running across the dark field, he heard barking and shouting, followed by a gunshot. Eventually, everything grew quiet. He once again saw the forest on the left, and moved deep into it. Only then did he slow the pace of his running. The morning found him near the tiny hamlet that the woman had told him about.

Flaxerman spent the whole day in the forest. By nightfall, he went back into the field. He walked alone, calm and proud as never before, because of the realization that he was moving and acting alone.

Semyon Gekht, Odin ("Alone"). GARF: f. Р-8114. op. 1. d. 163. pp. 7-8.