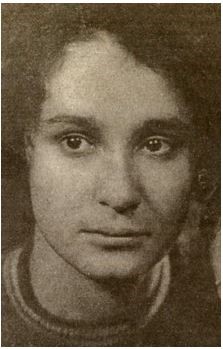

Sofia Anvaier was born in 1920 in Moscow. Her father worked in the state trade, while her mother and maternal grandfather were physicians. Following in their footsteps, Sofia enrolled in the 1st Moscow Medical Institute (University) in 1938. On June 23, 1941, the second day of the Soviet-German war, she volunteered for frontline duty. She served at the 505th Mobile Field Hospital, which was attached to the 19th Army. In September 1941, Sofia Anvaier was captured by the Germans and sent to a POW camp in Viazma (western Russia).

In November 1941, Sofia narrowly escaped being identified as a Jew. On that day, a squad of SS-men arrived in the Viazma camp and carried out a selection. Sofia Anvaier would write in her postwar memoirs:

"[Through a window] I managed to see what was going on in the courtyard. It was a pogrom of Jews. The SS-men selected Jews and drove them to the right. By that time, having spent more than a month at the camp, I had come to regard death as more desirable than life … but when I saw how they killed Jews, how the SS men baited them with dogs… I imagined what they could do to a woman and decided to linger a little on the stairs, preferring to be shot right then and there, on the spot. This was impossible, as the human stream pushed me into the courtyard. Immediately, a tall SS officer rushed up to me.

– A Yid?

– No, a Georgian [Sofia was black-haired, which was atypical for Russians]

– Last name!

– Andjaparidze."1

"Andjaparidze" had been the name of one of her fellow students in Moscow, and this ruse saved her life: all Jewish POWs in the Viazma camp were tortured and killed before her eyes.

Thanks to her medical training, Sofia was employed as a camp nurse. In 1942, during a face-to-face conversation with a young POW, the latter advised her not to wear her hat, because it made her look Jewish. He added: "I happened to overhear that your real name is Anvaier". He suggested that she volunteer to be transferred to another camp, deeper in German territory, where nobody would know her. Sofia realized that someone who had known her previously must have disclosed her Jewish origin and real name. Following the POW's advice, Sofia registered for a transfer. In May 1942, she arrived at a labor camp, where she worked first as a nurse at a Lazarett, and later as a laborer. In May 1944, the Germans learned that Sofia was cooperating with a clandestine resistance cell active in the camp. After brutal interrogation and torture, she was sent to the Stutthof Concentration Camp.

In summer 1944, Anvaier witnessed the arrival of Lithuanian Jews at Stutthof. While some of them came from Vilnius (Vilna) and Kaunas (Kovno), most of them were former inmates of labor camps in Estonia, to which they had been deported in 1943. A large percentage of the deportees was made up of families, who had been told that they would be transferred to "good labor camps". This, of course, was a lie: upon arrival, children, adult women, and adult men were separated and taken to different destinations. Sofia Anvaier recalled:

"Family members were clutching at each other, women clasped children, men tried to defend their kin… The screams of those who were beaten, the cries of the children, the yells of the SS-men, the barking of the dogs resounded through the camp for a long time…. The camp population, having seen the previous Jewish transports, knew the truth: the children would be killed; the women would be left in Stutthof for a time, while the men would be sent elsewhere, probably to Auschwitz."2

In 1945, Sofia, together with some Polish inmates, was transferred to the Dirschau camp. It was in this area that she and her comrades were liberated by the Soviets in March 1945.

The Soviet liberation led to a year-long screening by SMERSH, the Soviet anti-spy agency. The Soviets refused to believe that a Jew could survive three and a half years of German captivity. Sofia later recalled a dialogue with her interrogator:

"I was called in for an interrogation. <...> The formal questions began: last name, first name, patronymic, year and place of birth, nationality [ethnicity].

– A Jew? But Jews do not return from there alive.

– I claimed to be a Georgian.

He looks at me for the first time.

– Do you know the language?

– No, I don't. And I did not conceal it.

– These are just tales... Where and how did you surrender to the enemy?"3

Only in February 1946 was Sofia Anvaier allowed to return to Moscow. However, her troubles did not end there. In lieu of a normal internal passport, she was issued only a temporary document. There followed another interminable round of interrogations. Eventually, she did receive a passport, and was able to resume her studies at the 1st Moscow Medical Institute. After graduating, she worked on Sakhalin Island, in the Russian Far East. Only in the mid-1950s – after the death of Stalin, and a change of attitudes toward former POWs and other individuals who had been stranded in German-occupied territory – was she able to return to Moscow. Her situation seems to have been worsened by the antisemitic turn of postwar Stalinist policy, which was manifested in the "Doctors' Plot", inter alia. From 1957 on, Sofia served as secretary of the department of former POWs of the Soviet Committee of War Veterans. At around the same time, she began to publish fragments of her memoirs in various Soviet magazines and journals.

Sofia Anvaier died in 1996. The complete and uncensored version of her memoirs, Krovotochit moia pamiat': Iz zapisok studentki-medichki [My Memory Is Bleeding: From the Notes of a Medical Student], was not published until 2005.