Early Years

Vasilii (Iosif) Grossman was born in 1905 in Berdichev, Ukraine, into a family that was far from traditional Jewish life. His father was an engineer who had been educated in Berne. His mother, who had studied in France, taught French in Berdichev. When he was a child his parents divorced. Grossman specialized in chemistry at the physics and mathematics faculty of Moscow State University, graduating in 1929. He then worked as an engineer in Donbass until moving to Moscow in 1933. In the mid 1930s Grossman stopped working as an engineer and from then on devoted himself to writing. Several of his interwar stories, including "V gorode Berdicheve" (In the town of Berdichev), about the Russian civil war, had a Jewish theme.

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Grossman volunteered for the Red Army. From August 1941 to August 1945 he was a correspondent for Krasnaia zvezda (Red Star), the main newspaper of the Red Army. His articles, which became very popular among Red Army readers, dealt with the main battles of the war: Moscow, Stalingrad, the Kursk salient, and the battle for Berlin. His story "Narod bessmerten" (The People Is Immortal) appeared in 1942 and was the first story published in the USSR about the war.

For his work as military correspondent Grossman was awarded the Orders of the Red Banner and the Red Star. In 1943 he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel. The official government awards list of December 1942 noted his activity in the battle of Stalingrad, which was one of the main events in the life of this writer. The citation noted his willingness to take a risk in order to gain information, as well as personal experience and first hand impressions of the fighting: "The writer Grossman, carrying out his duties as a correspondent, on more than one occasion took part in combat, in the process of which he demonstrated valor and courage. He made his way into the most advanced units, right up to those keeping an eye on the enemy's movements, during the tensest days of military activity. At present he is the only writer who is participating in the fighting for Stalingrad and he often goes into the city with battalions and companies, where he collects literary material [i.e., materials for his articles].' Despite the fact that this was hardly recommended, while in the army Grossman kept a journal in which he jotted down much information that did not correspond to Soviet propaganda. If the journal had fallen into the wrong hands, he would certainly have ended up in the Gulag.

Grossman and the Holocaust

An important part of Grossman's creative work of during the war was devoted to the topic of the mass annihilation of the Jews. The attention to this theme was, among other things, connected with the facts that his mother had remained in Berdichev, which had been occupied by the Nazis and that Grossman realized that he was unlikely to ever see her again. This resulting feelings of helplessness and guilt became an important aspect of his life. Even though he did not directly express them in any of his prose writings. However, he did express his concern and his anger in a letter he sent to his father in March 1943: "No, I don't believe she is still alive. I travel all the time around areas that have been liberated, and I see what these accursed monsters have done to old people and children. And Mama was Jewish. A desire to exchange my pen for a rifle is getting stronger and stronger in me." In January 1944, when he arrived in Berdichev, which had just been liberated from the Nazis, Grossman wrote: "The only thing I am hoping for is to find out about her [Mama] last days and her death…. I've understood here how dear to each other the handful of survivors must be" (Antony Beevor and Luba Vinogradova, A Writer at War: Vasily Grossman with the Red Army 1941–1945, New York, 2005, pp. 224, 254-255).

Grossman's first story that deals with the Holocaust, "Staryi uchitel'" (The Old Teacher), appeared as early as in July 1943. On November 25 and December 2 of the same year the Jewish Anti-fascist Committee's newspaper Eynikayt published a Yiddish translation of his "Ukraina bez evreev" (Ukraine Without Jews). That unfinished article expressed the reaction of many Jewish soldiers and officers of the Red Army who found only graves in the places where Jews had lived and who learned of the murder of their dear ones there. In "Ukraine Without Jews" Grossman wrote:

"In Ukraine there are no Jews. Nowhere - not in Poltava, Kharkov, Kremenchug, Borispol, not in Iagotin. You will not see the black, tear-filled eyes of a little girl, you will not hear the sorrowful drawling voice of an old woman, you will not glimpse the swarthy face of a hungry child in a single city or a single one of hundreds of thousands of shtetls [small towns].

Stillness. Silence. A people has been murdered" (Vasily Grossman, "Ukraine without Jews," trans. Polly Zavadivker, Jewish Quarterly 58, 1 [2011], p. 13.)

In 1944 Grossman entered the Nazi camps of Majdanek and Treblinka, which had just been liberated by the Red Army, and also the ruins of the Warsaw and Łodz ghettos. In November of that year he published his long article "Treblinskii ad" (The Hell of Treblinka), in which one of the main topics was the mass murder of Jews. In 1945 "The Hell of Treblinka" appeared as a separate publication that was used later as testimony by the prosecution at the Nuremberg Trial.

In the fall of 1943 Grossman joined the major Soviet project about the Holocaust, Chernaia kniga (The Black Book), being prepared under the editorship of Ilya Ehrenburg. From the late spring of 1945, after Ehrenburg withdrew from editorship due to disagreements with members of the Jewish Anti-fascist Committee (JAC), Grossman became editor of the book project. Together with members of the JAC, Grossman attempted to save the book by introducing many changes required by Soviet censorship but, ultimately, despite their efforts, the book was not allowed to be published.

After the war Grossman continued to write works about the war. His main works were the novel Za pravoe delo (For a Just Cause), that he had begun in 1943 and completed six years later, and its sequel Zhizn' i sud'ba (Life and Fate), which was completed in 1959. The first novel, about the battle of Stalingrad, which was published in 1952 after exhaustive reworking required by Soviet censorship, was severely criticized in the Party press. However, Life and Fate had an even harsher fate: it was completely banned. The main Party ideologist, Mikhail Suslov, told Grossman that if the work would ever be published in the Soviet Union that would be not before 200-300 years from then. All the materials of the book were confiscated by the KGB. However, in the mid-1970s, after Grossman had died, the microfilm of a hidden copy of the novel was secretly transmitted abroad, where it was published in 1980. That novel, which some scholars consider the best Russian novel of the 20th century, devotes considerable attention to the Holocaust. One key section is a farewell letter written in a doomed ghetto by the mother of the main hero. Grossman's last prose work Vse techet (Everyhing Flows) was also not published in the USSR.

Vasilii Grossman died in 1964 in Moscow.

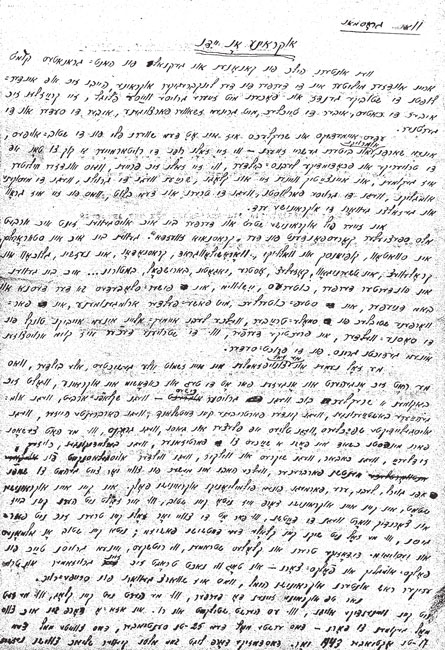

Vasilii Grossman's 1941 entry from his journal

In his journal in 1941 Vasilii Grossman jotted down his impressions of a visit he made to a tank brigade whose commander was a Jew, Colonel Abram Khasin. Grossman recorded as follows a conversation he had with another of the brigade's officers who was Jewish, Captain Kozlov:

"At Khasin's tank brigade, Captain Kozlov, the commander of the motorised rifle battalion, was philosophising about life and death while talking to me at night. He is a young man with a small beard. Before the war he was studying music at the Moscow Conservatoire. 'I have told myself that I will be killed whatever happens, today or tomorrow. And once I realized this, it became so easy for me to live, so simple, and even somehow so clear and pure. My soul is very calm. I go into battle without any fear, because I have no expectations. I am absolutely convinced that a man commanding a motorised rifle battalion will be killed, that he cannot survive. If I didn't have this belief in the inevitability of death, I would be feeling bad and, probably, I wouldn't be able to be so happy, calm and brave in the fighting.'…

Kozlov told me that in his opinion, Jews aren't fighting well enough. He says that they fight like ordinary people, while in a war like this Jews should be fighting like fanatics."

From: Antony Beevor and Luba Vinogradova, A Writer at War: Vasily Grossman with the Red Army 1941–1945, New York, 2005, p. 96.

1941 Letter of Vasilii Grossman to Ilya Ehrenburg about Antisemitism

In 1941 the writer Mikhail Sholokhov allowed himself, in the presence of Ilya Ehrenburg, to say that during the war while Russian were fighting at the front, the Jews were carrying on business in Tashkent. This remark, which aroused Ehrenburg's anger, became known to Vasilii Grossman. In a letter sent to Ehrenburg in late November 1941 Grossman stressed the injustice of Sholokhov's accusation:

"Several times, with pain and scorn, I have recalled the antisemitic slander of Sholokhov. Here on the Southwest Front there are thousands, tens of thousands of Jews. They go with automatic weapons into snowstorms, break into towns occupied by the Germans, and perish in battle. I have seen all this. I have also seen the glorious commander of the 1st Guards Division Kogan, and [Jewish] tank crew members and intelligence officers. If Sholokhov is in Kuibyshev [the temporary Soviet capital, located far from the front lines], don't fail to tell him that the comrades from the front know about his remarks. He should be ashamed."

From: Boris Frezinskii, ed., Pochta Il'i Erenburga: Ia slyshu vse 1916-1967 (The Correspondence of Ilya Ehrenburg: I Hear Everything, 1916-1967), Moscow, 2006, p. 75.