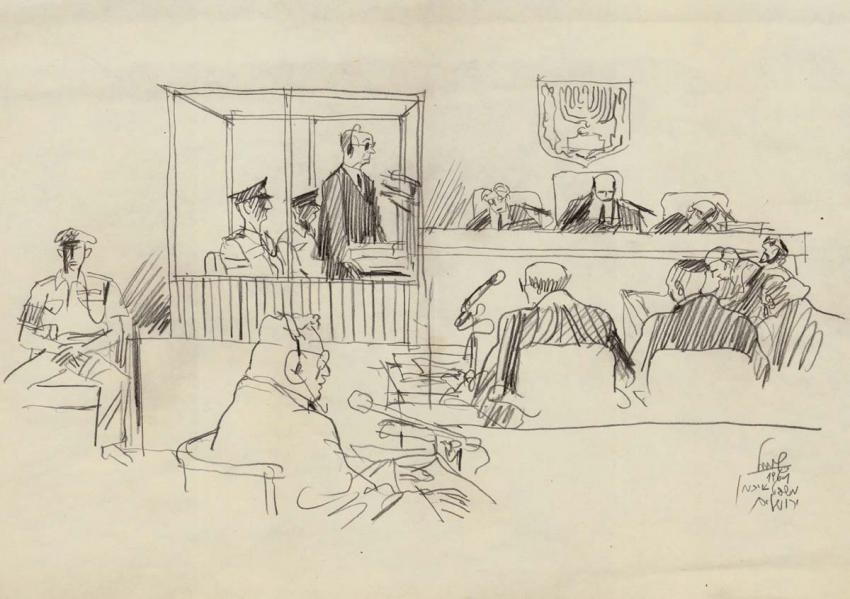

As we go to press with Yad Vashem Studies, volume 39, number 1, we are also marking the fiftieth anniversary of the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel. This was the first trial of a non-Jewish defendant under Israel’s Nazis and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law, passed on August 1, 1950. Until the Eichmann Trial and afterward, the law was applied mainly in trials against Jews in Israel who were accused of helping the Nazis in their persecution and murder of other Jews. The Eichmann Trial riveted a nation and much of the world. It was conducted before a visitor-packed courtroom, was listened to daily on radio by tens of thousands of Israelis, and was reported regularly in dozens of newspapers in many countries. For Israel and the hundreds of thousands of survivors who had settled there, the trial was in part a kind of cathartic release. It made the case against the defendant while also telling the story from the victims’ perspective through Holocaust survivors’ testimonies. This was the first mass hearing of Holocaust survivors’ testimonies in Israel, and according to many scholars it began a change in how Israelis looked at the Holocaust and its Jewish victims. Research on the Holocaust since then has been influenced by this trial in many ways, such as in scholars’ reliance on survivor testimony as one of their basic research tools. Most of the articles in this edition of Yad Vashem Studies have a connection to issues and perspectives raised in the Eichmann Trial, although this issue is not devoted to extensive discussion of the trial itself.

Shmuel Katz Eichmann Trial, 1961 Pencil on paper

Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum

Gift of the artist

I would like to take this opportunity to welcome three new members to the editorial board: Christopher R. Browning, Michael R. Marrus, and Michael Wildt, prominent scholars whose reputations precede them. In their distinguished careers, Chris, Michael, and Michael have been dealing extensively with the core issues of the Holocaust, many of which arose in the Eichmann Trial and in other Nazi war crimes trials. I am delighted that they have agreed to join the editorial board. Their extensive experience, knowledge, insight, and perspective on issues and articles have already enriched our journal and enhanced its content. I very much look forward to working together with them.

The volume is dedicated to the memory of Maxime Steinberg, the Belgian Jewish historian who pioneered the study of the Holocaust in Belgium, the reactions of Belgian Jewry, and that country’s confrontation with the Nazi occupation at the time and in its collective memory. One of Steinberg’s early research efforts related to the legal case against Ernst Ehlers, the former SS-Obersturmbannführer and governor of Brussels and later a judge in West Germany. Ehlers committed suicide before the trial, but Kurt Asche, Eichmann’s man in Brussels under whose watch most of the Jews were deported, was convicted. Steinberg laid the foundations for Holocaust research about Belgium and had a seminal influence on the teaching of this subject in Belgian schools and universities, as well as in its commemoration in Belgian museums. The volume opens with Insa Meinen’s article on Steinberg’s work.

The research articles in this volume address Jewish reactions during and after the Shoah, the question of rescue during the Shoah, reactions in North America, and more. Scholars from six countries have contributed to this volume with their nuanced examinations of these subjects.

Ingo Loose, Christoph Kreutzmüller, and Benno Nietzel examine Jewish strategies for economic survival in Germany in the face of the ongoing government onslaught in the first ten years of the regime, through a comparative analysis of the three largest Jewish communities of the time: Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, and Breslau (Wrocław today). The authors show that the Jews’ initiative in these three communities resulted in a limited measure of success in maintaining some level of economic viability until late 1938. The size of the city and of the Jewish community enabled some Jewish businessmen to elude the regime’s persecution or adapt their business enterprises for some time. Their success at maintaining a measure of financial viability helped the communities maintain their various welfare and relief efforts for less fortunate Jews. These findings run counter to the impressions found in previous research on German antisemitic policy-making and Jewish responses in the Third Reich.

Artur Szyndler tells the remarkable story of the attempt by Oświęcim (Auschwitz) Judenrat head Leon Schönker to arrange for large-scale Jewish emigration from the Katowice district of occupied Poland in the very early stages of the German occupation. In October 1939, the German occupying authorities ordered him to create a regional emigration bureau in Oświęcim, with Palestine as a main emigration destination for tens of thousands of Jews. Soon Schönker led a Jewish delegation to Berlin, where he negotiated with Adolf Eichmann and other Nazi officials. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in New York received regular reports from Schönker and was meant to help fund the emigration. The efforts lasted approximately half a year, until the Germans dissolved the emigration bureau. This rescue by emigration effort was part of a broader picture of attempts by Jews inside and outside Poland to organize Jewish emigration during the first months of the occupation, but this was the only one that saw Polish Jews travel to Germany in order to negotiate with government officials. This perhaps suggests a seriousness of intent on the part of the German authorities at the time.

Avihu Ronen, Hadas Agmon, and Asaf Danziger examine the development of attitudes in Israel and among survivors to Jewish officials under the Nazis during the Holocaust, through the prism of the war crimes trials of Hirsch Barenblat that began in March 1963, less than a year after the conclusion of Eichmann’s appeal. Barenblat served as a Jewish policeman in Będzin, in the same region as Schönker, and then as chief of the Jewish police there. He was accused by some survivors from the city of having brutally turned Jews over to the Germans for deportation to death. Barenblat was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison in the first trial, but was acquitted in the appeal. The Eichmann Trial’s very high profile and the passions that it released were not repeated in this trial. The authors find less public interest than for the Eichmann Trial, less party dogmatism in survivors’ testimonies than in earlier trials against Jews, and more sensitivity of the survivors, the courts, the press, and the public to the dilemmas faced by Jewish officials during the Shoah. People testified as they believed. Thus, some resistance people testified on Barenblat’s behalf, and others to the contrary. There was a less dogmatic view of the institutions of the Judenrat and the Jewish police than earlier. The authors suggest that the Eichmann Trial may have served as a sort of catharsis, releasing survivors and the public from the stereotypes regarding certain kinds of people and functions during the Holocaust.

Kobi Kabalek analyzes the background to the development of the concept of honoring the “Righteous Among the Nations” in Israel. He finds that discussions of this, out of a sense of gratitude and obligation, predated the creation of Yad Vashem by quite a few years. Yet, it took until 1963, several months after the conclusion of Eichmann’s appeal, until the definition of the Righteous and the form and context of the honor were determined. The discussion of these fundamental questions was caught up in broader Holocaust questions and in political debates, such as the understanding of “martyrs” and “heroes.” Survivors wishing to thank their rescuers publicly began finding ways to honor these people and ultimately generated a groundswell of pressure that led Yad Vashem to decide and act on these questions.

Two articles examine reactions in North America — Ulrich Frisse on the reporting in the Toronto Daily Star during the Nazi period, and Hava Eshkoli Wagman on attempts to organize Jewish refugee settlement in Alaska. Ulrich Frisse’s pioneering analysis of the reporting on the Shoah in the Toronto Daily Star, Canada’s largest and most influential newspaper, finds that the persecution and murder of the Jews was reported widely and in relative detail throughout the entire Nazi era. Frisse places his study in the broader context of what Canadians learned about the persecution and murder of the Jews in real time, who provided them with this news, and how the paper dealt with it. He combines content analysis of what was reported with an analysis of the correspondents who wrote and filed the reports, and the editors whose decisions determined what the readers would read (or not) and on which page it would appear. The reports were inconsistent in their detail and at times even omitted mention of Jews when these were the prime subject of a report on a camp or an event. Still, as Frisse shows, the Star devoted more space to Jews in relation to the Shoah and to other issues concerning Jews than to any other group during this period. That the Canadian government did not do more on behalf of the Jews, he concludes, was not for lack of sufficient knowledge, but rather in spite of it.

Hava Eshkoli Wagman looks at the little known case of efforts by a variety of rescue advocates in the United States to develop a refugee haven in Alaska. Whereas the idea of settling Jewish refugees in Alaska has been mentioned in passing in the historiography of the Holocaust, this subject has never before been researched thoroughly. Eshkoli Wagman shows that a variety of rescue advocates, particularly Jews, tried to interest US Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes and other officials from 1938 onward in the idea of settling large numbers of Jewish refugees in this vast and very sparsely populated territory. Some of these plans garnered a certain interest from Ickes and among his staff, but none of the privately initiated plans was realized, largely for internal American and Alaskan political reasons. What is clear is that refugee settlement in Alaska was on the rescue advocates’ agenda.

Four review articles on recent important books complete this volume: Pim Griffioen on Insa Meinen’s Die Shoah in Belgien; Christopher R. Browning on Das Amt und die Vergangenheit: Deutsche Diplomaten im Dritten Reich und in der Bundesrepublik by Eckart Conze, Norbert Frei, Peter Hayes, and Moshe Zimmermann; Jan Tomasz Gross on Barbara Engelking and Dariusz Libionka’s Żydzi w powstańczej Warszawie; and Yehuda Bauer on Agnieszka Bieńczyk-Missala and Sławomir Dębski, eds., Rafał Lemkin: A Hero of Humankind.

Whereas the articles and reviews in this issue do not all relate to Maxime Steinberg’s work directly or to the Eichmann Trial, issues raised by both that still trouble us today are the subjects of discussion here. Perpetrators and their motivations, Jewish responses and the dilemmas they faced, varied attempts, sometimes desperate, to rescue European Jews, reactions of the Western world and the Jews’ non-Jewish countrymen to the persecution and murder, and more are among the issues that exercise us in this edition of Yad Vashem Studies, issues that stand at the heart of the Shoah.