Our backgrounds were completely different: Yisrael’s parents were lower middle-class Warsaw Jews and they died in the ghetto, leaving Yisrael in charge of his little sister, whom he managed to place in Janusz Korczak’s orphanage. He then had to watch, helplessly, as she was marched together with Korczak and all the other children to the trains headed for Treblinka.

I made aliyah from Czechoslovakia with my parents in 1939, on the eve of the war, and while Yisrael was dealing with the loss of his family in the ghetto, I was playing football in Haifa.

He was a member of Hashomer Hatzair, and his madrich (counselor) was Mordechai Anielewicz, but there was no real bond between the two. Yisrael fought in the Warsaw ghetto uprising, and he lost an eye to a German bullet. He was taken care of, for a few days, by Anielewicz’s girlfriend.

Yisrael married Ariella Gelbgras in 1942, but she later died in Majdanek. He was shipped to Majdanek, and volunteered for a transport “elsewhere,” and that transport, of Jews and non-Jews, ended up in Auschwitz. The Polish clerk who assigned work for the new arrivals turned out to be a childhood friend of one of Yisrael’s teachers. He assigned Yisrael to a job in Monowitz, the industrial sub-camp of Auschwitz, where he had a chance to survive, and helped him in other ways. He undoubtedly saved Yisrael’s life. Until the end of his life, also in my very presence, Yisrael tried to find out what had happened to his Polish rescuer, but he failed. He used to complain to me in frustration that he was unable to fulfill that basic moral obligation.

He became a member of the Jewish underground in Auschwitz, and participated in smuggling gunpowder, obtained by a group of Jewish girls in the workplace, to the Sonderkommando in the gas chamber complex. The rebellion of the Sonderkommando in October 1944 was the result. When the Germans abandoned Auschwitz, and the death marches began, Yisrael was among those transported to Mauthausen, from where he was marched twenty-eight kilometers to the hellhole of Gunskirchen — no water, no food. After a few days, they were liberated by the Americans.

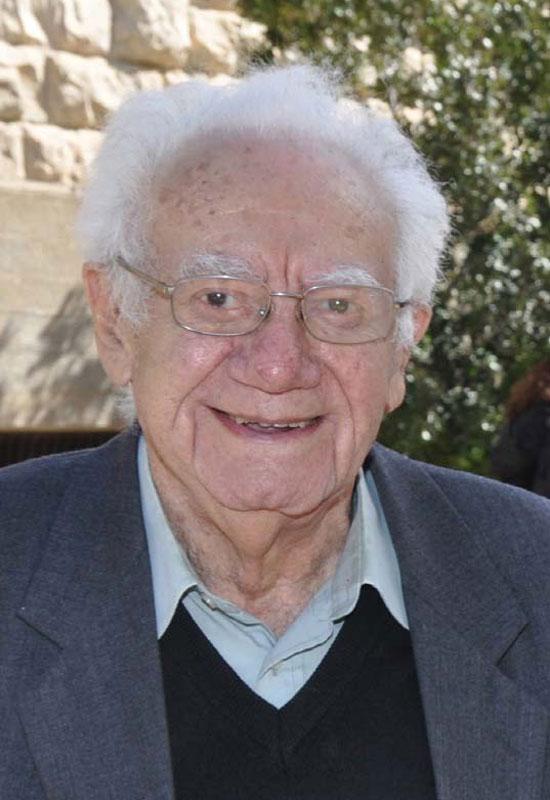

After liberation, a very sick Yisrael Gutman was to be sent to Switzerland to recuperate but he went to Italy with the Bricha organization instead. After being in charge of children and youngsters in a camp in Italy, he finally reached Israel, and joined Kibbutz Lehavot Habashan, where he married Irit, the daughter of Polish Jews. He became very active in the kibbutz movement and began writing books about the Holocaust even before he received the approval of his kibbutz to study in Jerusalem. He had not finished his high school studies in Warsaw, and in Jerusalem he was to do his bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Before that, in 1961, he joined Abba Kovner and a group of others, including myself, who founded the Moreshet institute for commemoration of the Shoah (now called Moreshet, Mordechai Anielevich Memorial Holocaust Study and Research Center), and in 1963 began publishing Yalkut Moreshet, one of the first Hebrew-language publications on the Shoah. We became friends, and then close friends, and remained so for fifty years, until he left us.

I shall not deal with his tremendous output of centrally important historical work on the Holocaust. Havi Dreifuss’s article in this volume does that most admirably. To me, Yisrael was more than just a colleague, he was a soul mate. He and I were sort of twins; we compared ourselves to the two old fellows in the Muppet Show — Yisrael had quite a sense of humor.

We often disagreed, but almost always presented a united front to others. Our basic position was identical, despite the differences in our backgrounds: we looked at the Shoah from a Jewish perspective. We wanted to tell the story of the Jews, which did not at all mean that we did not deal with the perpetrators, and the others, often inaccurately referred to as “the bystanders.” But the emphasis was on the Jews. I learned to read Polish, and a rather skeptical Yisrael gave me Polish materials to read. He never quite believed I could master the language in which he thought and dreamt.

We used to meet every week, usually more than once, in his home (after he had left the kibbutz in the wake of the tragic death of his son, Nimrod) or at The Hebrew University, and later at Yad Vashem. Our offices in both institutions were next to each other, so we walked into each other’s office and talked. Endlessly.

We made a conscious decision that I should concentrate on the university, and he on Yad Vashem, for our main efforts. But then I persuaded him to replace me as Head of the Institute of Contemporary Jewry at the university, and I became more active in Yad Vashem. He founded the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem, and it was self-understood that I would follow him there as director. We both became Academic Advisers at Yad Vashem.

He was invited to go to Germany to meet with Social Democratic teachers, friends of Israel, and people who seriously wanted to deal with the German past. He did not want to go, but then he said only if I went with him and he could speak English would he go. The Germans agreed, and so we went together to Würzburg, and he made a tremendous impression on our hosts. Then, when I was about to make my first visit to Auschwitz, I said to him that I would only go if he came with me and would take me around the camp. So, again, we went together, and he educated me about Auschwitz.

I corrected his speeches, and he guided me in my contacts with Polish colleagues. Articles about the Holocaust that either of us wrote were almost always read, commented upon, and corrected by the other. He was a real expert: no important book ever escaped him, and he could read languages that he could not speak — just like me — so we complemented each other.

As Havi Dreifuss has correctly noted, we disagreed on some issues, especially on the crucial question of the relationship between the concepts of the Holocaust and genocide. His view was that the Holocaust was the result of a unique convergence of circumstances and background that was not going to repeat itself. Paradoxically, this was also the view of Raul Hilberg, with whom we both had very basic disagreements. Hilberg never related to the question of “Why?” publicly, but he stated his view in closed circles, for instance, quite vehemently (in German!), in Heidelberg, which both of us attended, sometime in the 1980s. I disagreed, and continue to disagree, with both, because I see the Holocaust as a genocide that has some parallels with other genocides, but is the most extreme and unprecedented case of that pathology. Both these friends of mine did not relate their views about the singularity of the Holocaust to any metaphysical or religious factors. They thought that the Holocaust was the result of such unusual conjunctions of factors, that it could not be repeated. We sometimes disagreed openly, in the presence of others, but mostly in private. That did nothing to shake our ironclad relationship; indeed, perhaps the contrary is the case: we looked forward to having arguments about genocide. But we agreed on just about everything else.

Though Yisrael and I had become, naturally very close, very early, there always was a private sphere that neither of us would invade. Not everything that was thought was also said. He had a sharp tongue, and was by no means simple to deal with — the tragedies he had gone through, including some years ago the death of Irit, his wife, were things that rankled him every day and every night. But he had a caring family, and that made it easier. My late wife, Ilana, was a bit afraid of him, but it was towards her that he showed his tender and caring side. He came to her funeral, and he wept as we embraced.

He was very critical in his assessment of others, colleagues and institutions; he did not share this openly with others, but he certainly let go when we were alone. He knew he could rely on me not to relate his feelings to anyone else. In the last few years, he became very downcast, and skeptical, as regards the prospects of Holocaust research in Israel, and again, I held a slightly different view. He often said to me that he hoped I was right, but he was not convinced.

He was my closest friend, and I did not even attend his funeral, because I received the sad message in the car on my way to the airport for a long trip. He was a truly great human being, and a great historian, balanced, thorough, never mixing his personal story with his historical insights. His knowledge of many historical periods, not only of World War II, was phenomenal; his MA thesis dealt with Hassidism, and he had an excellent grasp of the whole of Jewish history. He would have thought that it was self-understood that I would speak at the funeral. I could not. So I write these comments instead.