“They Are So Alive Inside Me”

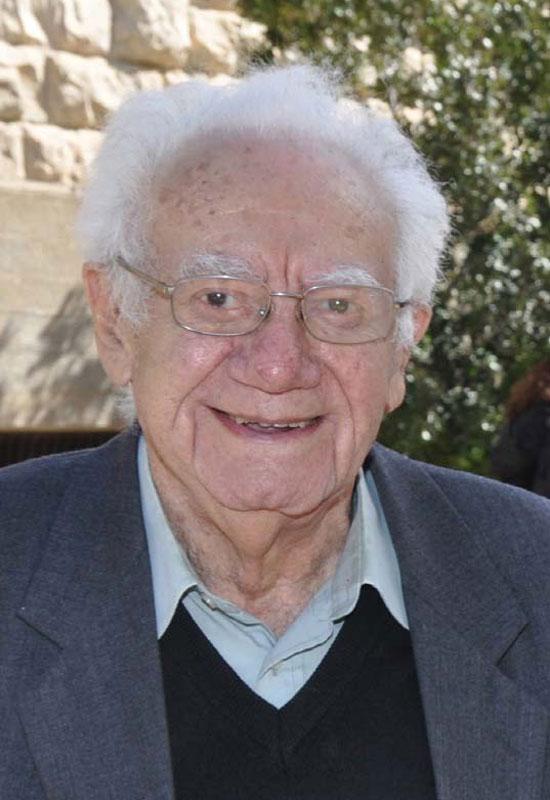

On Tuesday, October 1, 2013, Prof. Yisrael Gutman, one of the giants of Holocaust research in Israel and the world over, passed away in bed in his Jerusalem home at the age of ninety.

Yisrael Gutman’s death marks a turning point in research into the fate of European Jewry during World War II not only due to the passing of a seminal historian who — together with his colleague, Prof. Yehuda Bauer, who remains with us — laid the foundations for this research field at the Hebrew University and Yad Vashem, but also because his death comes to painfully remind us of the steadily dwindling generation of survivors. Indeed, Gutman was among the researchers who personally experienced the horrors of that era and, once it ended, had the psychological fortitude to subject the era to critical, balanced, and painstaking investigation.

Yisrael Gutman was born in Warsaw in 1923 to a warm Jewish family. His father, Benjamin, a worker at a rubber toys factory, was a Zionist who carried in his pocket a picture postcard of the laying of the Hebrew University cornerstone. The life of his mother, Sarah, revolved around her three children — Regina (Rywka), Yisrael (Jurek), and Genia (Golda). He spent his childhood within his extended family, with Jewish and Polish friends from school and the neighborhood, and with the books that he read voraciously. He began to consolidate his social and political worldview at an early age, not only at home but also — and perhaps mainly — at his HaShomer HaTza’ir youth movement branch.

The outbreak of World War II transformed Gutman’s life straight away. The vicissitudes of the war undermined the family structure and social connections of the Jews of Warsaw; even before ghettoization, his father and his elder sister died in succession. “[Each member of the family] now focused on his own distress. Only [Yisrael’s] mother and her two young children followed his father’s and sister’s coffins.”

Several months later, after the Jews of Warsaw were ghettoized, Yisrael’s mother contracted typhus. Placed in the ghetto hospital as her condition worsened, she soon died and was buried along with tens of thousands of others in the Jewish cemetery. Before her death, she charged seventeen-year old Yisrael with the care of his nine-year old sister Genia.

As social and family relations unraveled, the HaShomer HaTza’ir youth movement became a haven for Gutman. The movement officially disbanded before the Germans occupied the city in order to protect its young members; the leadership and older members left the city along with the masses of refugees who fled out of fear of the occupier and at the behest of the Polish command. Even so, the remaining members of the movement continued to meet and help each other. The return of some older members — Mordechai Anielewicz, Szmul Breslau, and Tosia Altman, among others — led to the intensification of movement activity and provided Gutman with a home in the literal sense. As Gutman testified later, “I did not remain alone; I was a member of a movement. It was a family as well. It was a connection, it was a shared idea, a shared organization, but also a family.” Since Gutman invested his time in the movement and his sister spent many hours alone, Ewa Gepner, sister of Avraham Gepner, head of the Judenrat’s Supply Department and one of the most important personalities in the ghetto, came to their aid. Ewa Gepner owned the factory that had employed Yisrael’s father before the war; she knew the family and their tragic circumstances. The Gepners helped Gutman to arrange a place for his sister in Dr. Janusz Korczak’s orphanage, which was already filled to overflowing. They also found work for him — first as a courier at a branch of the Supply Department and afterwards as a laborer in a plant that produced artificial honey and jam.

Now Gutman could pledge all his energy to movement activity. A young alumnus of the movement by now, he participated in seminars for older members and in educational activity, even organizing activities for children in punkten (gathering places) in the ghetto. Subsequently, he recalled having told them children’s stories that he had memorized and describing the Land of Israel on the basis of details that he had heard in movement settings and stories that he had made up. Gutman was recruited by Breslau to write and help distribute underground publications; and when the Anti-Fascist Bloc was established, he began to take basic military training under its auspices. He admired the movement leaders, the charismatic Breslau and above all Anielewicz, but felt that an ideological dispute that he had had with Anielewicz continually stood between him and the latter like an invisible wall. In his few free hours, Gutman visited his sister at Korczak’s orphanage. Although he apparently exchanged few words with the “Old Doctor” himself — he spoke mainly with Korczak’s loyal assistant Stefa Wilczyńska — he was grateful for the warm home that they gave his little sister.

When mass deportations to Treblinka began in the summer of 1942, the lives of the Jews in the Warsaw ghetto, including Yisrael Gutman’s, were overturned instantly. HaShomer HaTza’ir, like other political and social movements, sought to protect its members from the deportation menace. Accordingly, Josef Kaplan, one of the movement leaders, instructed young members to gather at a workshop that was thought to have a good German cachet — a carpentry factory run by Alexander Landau, a public activist and manufacturer who maintained close ties with the movement due to the activity of his daughter, Margalit. Gutman, a young man with good movement connections and no commitment to older parents or younger siblings, was better positioned than his comrades. Unlike them, he did not have to consider whether to help his family — who, as noted, by then were no more — but he was unsure whether or not to take his sister Genia into his care. Subsequently, he described one of his last visits to her:

We sat on a wooden bench and talked. I said that I had promised our mother, back then, to protect and take care of her. A disaster is unfolding: people, families are being separated and taken to an unknown place. We have to stay together ... I’ll try not to be separated from her. But maybe I’ll have to start working again, I have to meet with the movement people and do as the movement says, and there’s no telling what might happen. Genia answered that she’d already sensed it ... She doesn’t want to leave the orphanage. It’s good for her here and she feels safe here ... I wanted to tell her that it’s very dangerous to remain at the orphanage because the Nazis won’t skip over the children, but I didn’t dare … It occurred to me that she knows ... I felt a strange choking sensation in my throat. In another moment I won’t be able to restrain my weeping, here, with my little sister looking on. I kissed Genia on the eyes, which so closely resemble my mother’s eyes, and I walked, walked faster and faster, without looking back.

Some two weeks later, Genia was sent to her death along with the rest of the children in Korczak’s orphanage. Gutman, frantic, rushed through the ghetto in a last desperate effort to rescue her. In his anguish, he even tried to reach the Umschlagplatz. However, he was held back forcibly by his movement comrade Eliahu Różanski and led, totally devastated, back to the movement center in Landau’s factory. The loss of Genia and his inability to protect her, as his mother had instructed, left a wound in Gutman’s life that never healed.

In the days that followed, Gutman experienced the horrors of deportation along with members of his movement and other ghetto Jews. Captured by the SS, he was taken to the Umschlagplatz and interned in a cattle car destined for Treblinka. Gutman managed to leap from the car, return to the ghetto, and along with some other movement members, survive the terror of the Great Deportation period by going into hiding. The movement leaders, who remained in the ghetto during the deportation and strove to rescue members, perished; chief among them were Breslau and Kaplan. Despite the multilevel crisis — personal, human, movement, and community — HaShomer HaTza’ir managed, largely by dint of Mordechai Anielewicz’s personality, to regroup after the deportation, redefine the members’ commitment to the movement, and integrate them into the activities of the Jewish Fighting Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa; ŻOB).

As a HaShomer HaTza’ir member who maintained contact with the organization throughout the war, Gutman naturally fit into the activities of the ŻOB. However, he did not take part in the initial combat operations during the second Aktion, the January 1943 or “small” uprising, in which many of his comrades, foremost Margalit Landau and Elek Różanski, perished. In the subsequent reorganization, the ŻOB assigned Gutman to a combat position in Mordechai Growas’ company at 37 Nalewki Street. When the big uprising broke out, the fighters in this unit were the first to open fire on the Germans. By then, however, Gutman was no longer with them. Several days earlier, a commander of the ŻOB asked him to set up a bunker where casualties of the uprising could be gathered. The reason for this assignment probably traced to his connections with the honey factory and the Supply Department, both of which had well-equipped bunkers at 30 Franciszkańska Street.

Gutman spent the ghetto uprising in the casualties’ bunker, to which one of ŻOB’s leaders, Arye (Jurek) Wilner, who had been injured in a Gestapo interrogation, had been brought. Due to Wilner’s presence there, the organization’s command headquarters, including Anielewicz, Altman, Lubetkin, and others, relocated to the bunker. For Gutman, this created an opportunity to approach the headquarters bunker personally; thus, he heard about developments in other parts of the ghetto. The surviving fighters from the brushmakers’ workshop also reached this bunker in the course of their retreat; Gutman was among those who helped them to reorganize. On the night of April 22–23, 1943, Gutman left the bunker with several comrades to extinguish a fire that had erupted on the roof of the building. They encountered Germans and, in the ensuing engagement, Gutman was shot in the face, near his eyes. He spent the rest of the uprising wounded and in agony in the casualties’ bunker he created. In early May, the bunker was discovered and the Jews hiding there were ordered to emerge. The injured Gutman, propped up by his comrades, found himself at the Umschlagplatz for the second time and was sent from there to Majdanek.

Gutman considered Majdanek his ghastliest stop during the war. Wounded in one eye, enfeebled by his terrible stay in the bunkers, and psychologically traumatized, he realized that his chances of survival in the camp were nil. Again, however, a comrade came to his assistance by helping to place his name on a list of prisoners to be taken to Auschwitz. In Auschwitz, the Polish Schreiber (record-keeper) of the bloc, Włodzimierz Zawacki, a Polish notary by trade, recognized Gutman as a secondary school pupil of a childhood friend from Warsaw and as a casualty of the ghetto uprising. By providing Gutman with food and medicine and concealing him during selections, he spared him from certain death. This, too, Gutman never forgot. Within several weeks, Gutman met up with members of HaShomer HaTza’ir, enlisted in Jewish underground activity in Auschwitz (in which Jews across the political and ideological spectrum took part), and even helped to obtain the explosives that the Sonderkommando used to blow up one of the crematoria in October 1944. Subsequently, his comrades from Auschwitz and the camp underground, most of whom had survived — unlike those in the ghetto — became his closest friends. In January 1945 he was sent on the death march to Mauthausen and was liberated in Gunskirchen on May 5, 1945.

The war now over, Gutman, assisted by the Bricha organization, moved on to the displaced persons camp at Santa Maria di Leuca, Italy, and was among the founders of the Aviv kibbutz (commune) there.

Quickly he integrated into HaShomer HaTza’ir activity in Italy and elsewhere. As an essential activist, Gutman remained in Europe even after his comrades at Kibbutz Aviv and many others began to head for Eretz Israel. Only after the United Nations General Assembly resolution to terminate the British Mandate did he act on his wish to leave the continent and take part in the future struggle for Jewish statehood. Before repatriating to Eretz Israel, however, Gutman requested, and received permission, to visit Warsaw. After the fact, he cited the report about the discovery of Ringelblum’s archives as the factor that lured him back.

During his brief stay in Poland, Gutman visited the ruins of the ghetto, the Jewish Historical Institute, and HaShomer HaTza’ir centers, and took part in movement activity. Then returning to Italy, he began to make his way to Eretz Israel, completing the voyage in early 1948. Although this had been his desire for years, his integration there did not proceed smoothly. The War of Independence had begun and the Hakibbutz Ha’artzi movement, through which he tried to make his way to one of the HaShomer HaTza’ir kibbutzim, had other concerns. Much time passed before Gutman managed to join Kibbutz Lehavot Habashan in the Galilee. Integration difficulties persisted; he felt foreign among the Sabras and among HaShomer HaTza’ir members who had left Poland before the war. Furthermore, he sensed a discrepancy between the ideal Eretz Israel that he carried inside him and its practical realization at Lehavot Habashan. Still, he would say about his stay there, “For the first time in my life, I felt the profound experience of belonging to a place, for better or worse.”

At Lehavot Habashan, Gutman met Irit Edelstein, a member of HaShomer HaTza’ir from Geneva. They wed and had three children: Nimrod, Dita, and Tami. Although he was employed in the kibbutz agricultural facilities, his impressive past and his writing and pedagogical talents gradually came to light. After his essay “How the Uprising Developed” was published in The HaShomer HaTza’ir Book, the movement asked him to suggest ways of integrating the paragonic leaders of the uprising into its education system. Concurrently, Gutman reestablished contact with the group of survivors from the Auschwitz resistance, who encouraged him to write their life stories. These were published in his first book, Men and Ashes: The Auschwitz-Birkenau Book. Apart from memoirs, Gutman blended testimonies and documents into the book and added a cogent and systematic account of the camp’s history, how it was organized, and the fate of the Jews who had been sent there.

Partly due to the appearance of this book, Gutman was invited to testify at the Eichmann Trial. On the stand, he described the activities of the Jewish underground in Auschwitz and the preparations for the Sonderkommando uprising. However, neither he nor any other participant in the Warsaw ghetto uprising was asked to speak about the uprising at the trial. This task was assigned to Antek Cukierman (Zuckerman) and Zivia Lubetkin, co-founders and commanders of the ŻOB and formative personalities in the field of Holocaust and uprising memory in the fledgling State of Israel. Gutman and his HaShomer HaTza’ir comrades considered this an especially stinging slap in the face, one that emphasized publicly their general exclusion from the pantheon of heroism that had been founded in the newly formed State of Israel.

For years, the HaShomer HaTza’ir people had felt that their role, both as a movement and as ghetto fighters and partisans, had been hidden from the public eye. The Ghetto Fighters House and Yad Vashem engaged in documentation and commemoration, but did so differently and with different emphases from those adopted by Gutman and his movement comrades, largely under the inspiration of Abba Kovner.

Gutman’s activity in the Moreshet Circle should be viewed against the background of this void; so should the publication of his book Revolt of the Besieged: Mordecai Anielewicz and the Uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto. The persona of Anielewicz as a member of HaShomer HaTza’ir and the centrality of the Warsaw ghetto uprising provided the motive, but the vehicle used to emphasize the importance of the uprising, the man, and the movement found expression in research, which became Gutman’s principal medium of communication.

This impressive work, recently reprinted in Hebrew and justly so, is not a classical academic study, least of all in comparison with his comprehensive study on the Warsaw ghetto. It is based almost exclusively on Jewish sources, lacks certain historical contexts, and inserts reconstructed excerpts of Gutman’s own diary along with other testimonies. In this of all of his books, however, Gutman reveals many aspects of his personal life in the ghetto era that he refrained from addressing afterwards with such candor. Furthermore, the book displays the qualities that Gutman invested in his writing before he entered academia as well as some of the principles that would distinguish his scholarly activity over the years: his focus on the lives of Jews in the Holocaust on the basis of their own sources and the ability to reconstruct and explain personal dilemmas as well as complex social interactions.

By emphasizing these elements, Gutman became one of the first to paint the Jews not as passive victims but as active and productive human beings who found themselves ensnared in an impossible reality. Furthermore, in response to the awards and lavish praise that Revolt of the Besieged earned, the kibbutz allowed Gutman to devote two years to study in Jerusalem, during which he cemented his relationship with Yad Vashem and Hebrew University, the institution whose picture postcard of its cornerstone laying ceremony his father carried in his pocket. When Gutman moved to Jerusalem in 1971 following the tragic death of his son Nimrod in military service, these two institutions became his academic homes. His activities at — the Institute of Contemporary Jewry at the Hebrew University and Yad Vashem — were mutually enriching and allowed his research, educational, and public activities to take off.

Gutman’s life story, his areas of research, and the nature of his academic and public activities seem to follow the strands of three personalities who left their imprints on him: Mordechai Anielewicz, Janusz Korczak, and Emanuel Ringelblum. His acquaintance and actual encounters with them were very different, but each personality influenced him in a fundamental way that helps us to understand his way of investigating and commemorating the Holocaust.

In the Footsteps of Mordechai Anielewicz

First and foremost, Gutman was a man of HaShomer HaTza’ir. His personality was shaped in the movement and his movement comrades accompanied him throughout the war and afterwards as well. Moreover, he referred back to the movement in innumerable private conversations when asked to say something about himself and the essence of his outlook and identity. His admiration for Anielewicz and his connection with the movement were the thematic underpinnings of his initial writings. Once he adopted the principles of topical, balanced academic writing, he dealt with additional movements and organizations in detail and touched on broader topics. Even here, however, the broad foundations that the movement imparted to him remain visible.

Gutman’s love and understanding of the lost world drew heavily not only on the HaShomer HaTza’ir worldview but also on his personality and on the Holocaust horrors that he would endure. He loved the alleys of the cities and the houses of the village and the shtetl; he loved the impossible attempt to cope with a reality that had never existed before.

Mainly, however, he loved people, loved the Jews of Poland. His familiarity with the Jews’ world and his personal qualities allowed him to write about them in fundamental, thorough, and comprehensive academic research that revealed the all-so-human facets of the individual Jew and Jewish society during the war. Due to his love for them, a love that drew on his parents’ home and the values of HaShomer HaTza’ir, even his critical scholarly writing exuded compassion and understanding for the Jewish masses that found themselves in the depths of an inferno.

His sharp criticism of Hannah Arendt’s book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil was based, it seems, not only on topical claims concerning Arendt’s unfamiliarity with the requisite historical contexts and the unbending judgmentalism that wafted from her remarks about the Jews — particularly the East European Jews and their leaderships — but also on slightly less topical arguments, e.g., Arendt’s contempt for the State of Israel and Ben-Gurion. Gutman’s heated rhetoric should also be viewed against the background of Arendt’s callous regard for the Jewish masses in particular. Addressing herself to the Warsaw ghetto uprising, for example, Arendt wrote, “The glory of the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto and the heroism of the few others who fought back lay precisely in their having refused the comparatively easy death the Nazis offered them — before the firing squad or in the gas chamber.” Gutman retorted,

Arendt proves again that she does not fully understand the specific value of the uprising. The rebels, as it were, merely forwent the easy death and chose the hard one. What, however, was the “easy death”? The easy death was very hard. Many walked toward it without knowing where the path led and where the final stop would be, while others, who knew everything but did not believe it to the bitter end, clutched a strand of hope like mountain climbers who, in the middle of their strenuous hike, suddenly find themselves hanging from and grabbing at the edge of a precipice.... They grope for the edge instinctively, in the irrational hope that something extraordinary will happen to save them. They postpone their demise as best they can in the expectation of a miracle. So it was with the victims of the Holocaust. The delusion of the Holocaust victim always found something to grasp in the Germans’ deceitful promises and, perhaps, in reasoning that said, and then whispered again, that one person would not do such a thing to another person and that as long as one’s soul exists matters may turn, things may develop, and the decree will be averted. It is this that struggles against the inevitable certainty.

In Gutman’s opinion, the disdain that wafted from Arendt’s writings led her to a total misunderstanding of the fate of European Jewry under Nazi occupation. For Gutman, any occupation with the Jews’ fate in the Holocaust must use as its point of departure the victims’ humanness and the Jewish understanding of the world before and during the war.

This approach was also manifested in the Moreshet Circle, the commemorative enterprise that he and his movement colleagues (Kovner, Bauer, and others) launched under the auspices of the Moreshet Institute in response to the exclusion of the uprising from the public discourse and the soft-pedaling of the movement’s role in the events. However, a deeper rationale was at work in this case, as Kovner explained in the choice of the title: “The name of this project is moreshet [legacy]. Why? Because we, the people ... are the heirs to the legacy of our great nation. We have not only Trumpeldor and Hirsh Lekert in mind but also those [sic] Judaism that is called passive, which is nothing but martyrology and walking to the stake.” Kovner provided the inspiration for these perceptions; Gutman and many others acted to shape them.

The activities of Moreshet and, in particular, the numerous issues of one of the few scholarly journals on Holocaust history that existed back then, Yalkut Moreshet, reveal a broad range of topics of interest. Yalkut Moreshet focused on more than ghetto uprisings and warfare; even in its first decade, it investigated German policy, the fate of Jews in various countries, and Yishuv organizations and their treatment of the Holocaust — all of which with academic rigor and the accompaniment of testimonies and documents. As time passed, its coverage was broadened to include social and cultural issues and philosophy.

It bears emphasis that the HaShomer HaTza’ir perception of the uprising itself — in Warsaw per se — concerns not the narrow expression of a specific action but a fundamental revelation of the human spirit. Thus, the Moreshet Circle viewed the uprising not only as the topic of an important historical discussion but also as an important vehicle for investigation of the Jewish individual and society and their actions under German occupation. Gutman’s sensitivity, in his research and public activities, to the fate of the Jewish public, down to its varied individuals, originated not only in his intimate familiarity with the object of his research but also in his special personality and worldview, nourished by the principles and values of HaShomer HaTza’ir. If so, it was only natural — but very moving nonetheless — to see the blueshirted members of HaShomer HaTza’ir escorting Yisrael Gutman on his final journey.

Gutman’s Educational Activities

One cannot assess Gutman’s career in Holocaust research without relating to his ramified educational activities. That he considered himself an educator, apart from everything else, may again reflect the influence of Janusz Korczak. Not only was one of his first publications about the Holocaust a curricular unit for its teaching, but Gutman also co-authored the main textbook used in teaching the Holocaust in the Israeli education system. In 1978 Gutman was part of a lobby of survivors and former ghetto fighters who turned to Zevulun Hammer, then newly installed as Minister of Education, and asked him to include a systematic, required unit on the Holocaust in the curriculum. When Hammer acceded and promised a thorough reform in Holocaust studies, the need for an appropriate textbook arose.

Thus, within a few years, Gutman, along with his friend and colleague Chaim Schatzker, published The Holocaust and Its Significance, soon to become the basic secondary school textbook on Holocaust history in Israel. An examination of the book reveals the worldview that guided its authors and its underpinnings in research. The first three introductory chapters deal with interwar Europe, the Jews who lived there, and the antisemitism that they experienced; they set the Holocaust within Jewish history and emphasize the centrality of persecution of Jews down the generations.

They have rather little to say about the Jewish leadership in the Holocaust due to the little research attention paid to this topic at the time. One chapter stresses the singularity of the Jewish fate in the Holocaust and also makes brief reference to North African Jewry. Jewish resistance and uprisings receive a chapter of their own, naturally enough; here the role and value of the Warsaw ghetto uprising is emphasized along with other patterns of response. The concluding chapters touch briefly on the she’erit hapletah (the surviving remnant) and patterns of remembrance as shaped largely in Israel.

Gutman, however, considered the development of research and education inseparable and was involved for years — sometimes intensively, sometimes partly — in the rewriting of texts for teaching the Holocaust. In 1999, for example, his Holocaust and Memory: A Textbook for High School, written with the assistance of Na’ama Galil of Yad Vashem, was published. This book was not an updated version of the 1980s textbook The Holocaust and Its Significance. It departed from its predecessor in several important matters, such as shifting emphasis from antisemitism to ideology; devoting much attention to the patterns of Jewish leadership that operated alongside, and sometimes against, the Judenrat; much more attention to the Jews of Western Europe and other areas, such as Romania and northern Africa; and the varied activities of the she’erit hapletah in the DP camps. This book also authentically expressed issues that concerned the research world at the time, including the Yishuv’s responses to and actions in view of the Holocaust and the image of the murderers. This textbook was a visceral reflection of Gutman’s aspiration to align teaching with the latest in research. Gutman’s role in writing important schoolbooks evidently mirrored his eagerness to convey the latest knowledge to the youth of Israel and the immense importance that he attributed to educational activity.

Gutman considered it the historian’s duty to serve society, including its young members. Apart from giving over knowledge, however, he championed the imparting of critical tools that would prompt students to ask how history is written. Accordingly, when involved in writing textbooks, he placed historical documents in them. His role in compiling the sourcebook Documents on the Holocaust should be viewed in this spirit. This collection became a basic text in teaching the Holocaust; even today, thirty-five years after it first appeared, it figures importantly for students in Israel and around the world. Contending with documentation — be it a German order, a Jewish diary, or a Polish testimony — was, for Gutman, an important part of training students and young researchers.

Gutman again demonstrated his commitment to education in his editing of the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. The impressive novelty of the encyclopedia and the long-term impact of this Promethean enterprise, published in 1990, can be appreciated only against the background of the period in which it was conceived and produced. In our era of mass information online, it is difficult to describe the pioneering nature of this thousand-entry encyclopedia, a seminal project that provided accessible, handy, and reliable information on a vast range of topics in Holocaust history. Within its ambit, Gutman had to review the most basic definitions of the Holocaust era, including the roots of the catastrophe, its contexts and personalities, and the main events and places in its history. Alongside seemingly obvious historical entries — antisemitism, ghettos, camps, etc. — it offered, for the first time, entries on literary and artistic aspects of the Holocaust as well as erroneous myths associated with it. The inclusion of such a broad and diverse range of views and aspects in one project and the ability to recruit 150 researchers from around the globe, including several from Poland who contributed their entries despite Communist rule in their country, are indicative both of the breadth of Gutman’s vision and of the power of his personality.

As an educator, Gutman took special pride in the International School for Holocaust Studies at Yad Vashem and cherished its educational activities. Gutman often criticized various educational aspects of teaching the Holocaust in Israel and abroad; his integrity did not allow him to refrain from criticizing educational enterprises in which he himself, or Yad Vashem, had been involved. As long as his strength endured, he took part in teacher training, attended international seminars, and participated in the school’s educational publications.

In the Footsteps of Emanuel Ringelblum

During the war, Gutman had only a superficial acquaintance with Ringelblum. Over the years, however, once aware of the scope of Ringelblum’s activity, his historical principles, and the documentary trove that was preserved by his merit, Ringelblum became, for Gutman, not only an object of research and veneration but also a veritable mentor.

Gutman, like Ringelblum, considered himself first of all a Jewish historian, a historian of the Jewish people, and for good reason he predicated his work on the connection between the fate of Polish Jewry in the Holocaust and their lives preceding the crisis. His area of expertise, however, was the Holocaust, and his prolific studies concern the main latitudinal topics of research into the fate of the Jews of Eastern Europe in the Holocaust, including antisemitism, the Jews’ lives in the ghetto and the camps, Jewish resistance, Jewish-Polish relations, rescue, youth movements, Jewish leadership, the she’erit hapletah, forced labor, and many others. Research on many of these topics has come a long way since Gutman wrote his first studies; they have been investigated at length and in depth, and recent studies often challenge the way Gutman presented these matters in his research. Even a sketchy review of Gutman’s writings, however, demonstrates his centrality in establishing the basic infrastructure of Holocaust research and, above all, research on the Jews’ fate in the Holocaust.

Gutman’s uniqueness is manifest not only in the range of topics that he tackled but also in how he did it, foremost in his emphasis on Jewish testimony as an indispensable tool in understanding the history of the Holocaust. If the Jews’ voice is central in Holocaust research today, it had not been so in the past. Not only had the Jews been less than “present absentees” at the Nuremburg Trials and the tribunals that followed; even historical research did not initially consider their voice essential in understanding what had happened. The most blatant example is Raul Hilberg’s principled attitude toward Jewish sources as inconsequential in Holocaust research. In Gutman’s opinion, the underuse of Jewish testimony distorted research in palpable ways such as errant disregard of Jewish responses to the Germans’ policies, including armed resistance; a unidimensional view of Jewish leadership; and total indifference to internal Jewish life.

Therefore, emphasis in Holocaust research on Jewish voices — in all their diversity — is the thread that runs through Gutman’s research activity. In Gutman’s opinion, the historian should expose the fate of the Jewish masses not only as victims but also as people, individuals, and a public — parents, children, and the elderly, community and social organizations, political parties, and youth movements. Gutman stressed the need to personalize the expression of the Holocaust within the research itself, and he did so in his scholarly writing, his ramified advisory services for museums in Israel and abroad, and his efforts, along with those of his colleagues at Moreshet, to integrate testimonies and documents into the studies published in Yalkut Moreshet.

The importance of the Jewish voice, in all its variants, appears to be one of Gutman’s first and most fundamental insights. His monograph on the Jews of Warsaw and the doctoral dissertation on which it was based demonstrate Gutman’s realization that occupation with the uprising entails thoroughgoing discussion of the lives of the Jews of Warsaw at large:

During the preparatory work for this book, I realized that the manifestations of resistance and warfare should not be dissociated from the general background of life under the burden of the occupation and from public life as it took shape during the occupation and ghetto period.... The meaning of resistance and warfare under these special circumstances cannot be properly understood without an understanding of the human and social conditions and stresses that came about during the Holocaust.

Indeed, although this study focused on the youth movements and their role in the resistance, Gutman carefully linked these topics to the history of the uprising and the fate of the Jews of Warsaw. His book deals not only with political organizational efforts and the official and unofficial ghetto leadership but also, and perhaps mainly, with the ghetto reality itself. Relating to daily life in the ghetto, for example, Gutman called attention not only to the dire distress manifested in the ghetto streets, including starvation, morbidity, and mortality, but also to manifestations of life that emerged amid the death that had been decreed against the Jews of the ghetto.

The lifestyle of the ghetto gave rise to a number of phenomena that were new to the area and unique to the atmosphere within the walls. For example, there was a “promenade” in the ghetto that attracted groups of young strollers, and special courtyards were outfitted with chairs and established as spots for sun-bathing. Skits and satires on daily life were performed in the ghetto’s theaters, and there was also a kind of folklore of the ghetto – popular heroes, special mottoes, jokes about the state of affairs, and even a special ghetto slang.

Authorship of a monograph as a way to explore one Jewish community in all its aspects during the Holocaust became an important research genre and Gutman left many disciples behind. As time passed, he advised students who wrote important monographs on an array of towns in Poland to broaden this line of inquiry to the Jewish population at

large, a topic that became central in these studies. The uniqueness of his approach to research in this respect stands out when one compares these monographs with other important works by authors outside the Israeli research world. Gutman’s students concentrated on Jewish society during the Holocaust from all angles and against all challenges, a subject that somehow was excluded from studies by scholars outside Israel.

However, Gutman never limited himself to Jewish sources alone; he also examined German administrative sources, those of local populations, and others. Non-Jewish documentation, as well as broad political aspects of the settings of the historical reality that he examined, always appeared in his analyses and his presentation of the Jewish themes.

Furthermore, Gutman was wary of sanctifying the Jewish voice, however central he considered it, and was mindful of the limitations of documentation written by Jews during and after the Holocaust. In fact, his methodological prudence led to severe allegations against him in the context of the Warsaw ghetto uprising; the main charge was that, as a member of HaShomer HaTza’ir and the ŻOB, he deliberately disregarded the role and importance of the Revisionist underground in the ghetto. Gutman, for his part, applied rigorous self-restraint in describing the activities of the Jewish Military Union (Żydowski Związek Wojskowy; ŻZW) and even wrote explicitly,

We have few primary sources that relate to the ŻZW’s ties with the Poles. On the other hand, as stated earlier, some Poles have come forward who claim to have maintained contact with the organization and supplied it with arms and other forms of assistance, though their testimony is not corroborated in the memoirs and writings of the ŻZW’s members or supporters within the ghetto, and there are testimonies that cast serious doubt on this. We may therefore assume that a number of the claims regarding aid tendered to the ŻZW contain self-serving and fabricated information. Some of these witnesses evidently discovered that few important members of the ŻZW survived; the sources that tell us about this organization are very scanty, leaving much leeway for exaggeration of (ostensible) actions that Poles took or roles that they played in preparing and carrying out the uprising. This hyperbole from the Polish side almost certainly reflects the Polish authorities’ tendency to inflate the Poles’ role in the ghetto struggle and uprising above and beyond what really happened.

Recent studies have revealed, little by little, how well advised Gutman’s caution was. Dariusz Libionka and Laurence Weinbaum proved that many of the reports about lavish assistance for the ŻZW from a Polish group were, as Gutman had suspected, groundless. These testimonies do not further our understanding of the ŻZW’s important activity during and after the uprising; at most, they may demonstrate how the uprising became an instrument for the aggrandization of specific individuals’ status in postwar Poland. Gutman, however, never confined his criticism to the ŻZW. When he discovered inaccuracies in the account of ŻOB’s activity after the death of Yitzhak Cukierman and the publication of his book A Surplus of Memory, he did not refrain from pointing them out clearly.

Thus, the sources — both Jewish and non-Jewish — became means and not ends in Gutman’s hands. He used them to uncover the fate of the Jews in the Holocaust and emphasize the voice of the victim as an individual who took action and remained productive within an impossible reality. A review of contemporaneous historiography shows that this approach, focusing on the Jewish aspects of the Jews’ fate under German occupation within their broad context — an approach crystallized by Gutman and his lifelong colleague, Yehuda Bauer — was the royal road. Initially adopted mainly by Israeli researchers, over the years it seems to have spread to researchers the world over. Thus, the impressive sixteen-volume research project of the German Federal Archives, the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich, and the University of Freiburg, Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen

Juden, takes up the Jews’ fate and even makes extensive and impressive use of both Jewish and non-Jewish sources. Christoph Dieckmann’s comprehensive work on the German occupation policy in Lithuania discusses the lives of the local Jews at length and in depth, and Christopher Browning wrote an entire study demonstrating the necessity of the use of Jewish testimony.

Furthermore, concern for the fate of the Jews in the Holocaust has long since ceased to be exclusive to Israeli or Jewish researchers; no few researchers, particularly those who investigate the Holocaust in Poland, became preeminent students of Yisrael Gutman. Barbara Engelking, for example, one of the most important researchers in this field today, goes to great lengths to describe the human aspects of Jews and Poles and their impossible encounters during the German occupation. Engelking and her colleagues in the circle of researchers at the Polish Center for Holocaust Research in Warsaw (Centrum Badań nad Zagłady Żydów) were warmly adopted by Gutman, who considered the formation of a generation of scholars in Poland who examine various aspects of Jewish life in Poland on the basis of copious documentation, including documents composed by Jews during or after the war, a veritable revelation. Gutman’s dramatic past and impressive personality resulted in the creation of strong personal relations with these researchers, and his awareness of the recent Polish discourse about the Holocaust soon made him a go-to person for them.

Indeed, Gutman participated for decades in the important Polish discourse on the Holocaust and the Poles’ role and responses to the Jews’ calamity. Gutman never flinched from asking tough questions; however, being rooted and well-versed in Polish culture, he also knew how to get his message across so that it would be heard. A possible example is an astonishing quotation that he cited from remarks by the famous literary critic and researcher Kazimierz Wyka in a discussion of Jewish-Polish relations during the Holocaust:

Even if I will be the only one to speak my mind and even if no one will back me on it, I will continue to claim: no, a hundred times no. This manner of behavior and these hopes are embarrassing, toxic, and lowly because the moral-economic stance of the average Pole toward the Jewish tragedy boils down to this: the Germans, by violating the Jews, are engaging in acts of murder. We would never do it. The Germans will pay the penalty for this crime; they have stained their conscience. But we merely derive benefit from it, and this, without sullying our conscience and without staining our hands in blood.

Through the lively polemics in which he participated in Poland, including acrid exchanges in which especially painful and mordant matters came up, Gutman upheld his role as a professional and topical historian despite being a survivor. The Jedwabne affair, for example, which made enormous waves in Poland and elsewhere in the early 2000s, shocked Gutman to the core. Although the facts themselves were not totally new to him and were not always described with absolute accuracy, the initiative taken by Polish civilians to murder Jews who had been their neighbors for many years, accompanying the massacre with ghastly abuse, infuriated him immensely. In private conversations, Gutman shed his rhetorical restraint and made caustic remarks about the Polish society that had not only stood aside as the Jews were being murdered but had also taken part in the atrocities. When relating to this as a professional historian, however, he maintained objectivity and balance.

Gutman’s academic integrity surfaced again in research on one of the topics most identified with his studies, Jewish resistance during the Holocaust. Here we cannot discuss the development of research in this field — much ink has already been invested in it — except to present briefly several changes that Gutman’s research on this topic underwent and how he developed, intensified, and expanded his discussions of the matter over the years.

In the early years, armed resistance to the Germans stood at the forefront of the public and research discourse in fledgling Israel. The first international academic conference organized by Yad Vashem (1968) dealt with Jewish resistance during the Holocaust. Gutman, already well known for his early books and for his activity at Moreshet and Yad Vashem, lectured at the conference on youth movements in the underground and the ghetto uprisings. In this case, however, the lively and tumultuous debates that broke out at the end of the sessions were measurably more important than the lectures themselves. Since it was the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Warsaw ghetto uprising and the twentieth anniversary of Israeli independence, the conference was attended by many individuals who had taken part in the events and responded to everything stated or insinuated there. Gutman was an active participant in these discussions; in fact, he spoke on behalf of the young members of the resistance by attacking the adult political leadership, totally rejecting the Judenrat, and stressing the absolute centrality of youth in putting together the resistance operations.

The moment Gutman began to relate to these issues as a researcher, however, his rhetoric became much more measured and profound.

In the mid-1970s Gutman turned his attention to the question of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust in a chapter in his book In Darkness and in Struggle: Chapters for Study of the Holocaust and the Jewish Resistance, and in a work devoted entirely to this topic, Struggle on the Path of Afflictions: Jewish Resistance to the Nazis during the Holocaust. Again, Gutman categorically rejected the argument that the Jews had put up no resistance in the Holocaust. However, even though he re-emphasized in these works the centrality of the phenomenon, he was keenly aware of the risks of banalization and apologetics that had attached themselves to research into this field and discussed them openly. Attempting to develop a balanced assessment of the extent and limits of Jewish resistance in the Holocaust, Gutman examined the reality of this resistance. To his way of thinking, the very possibility of widespread Jewish armed resistance was obviated by the restricted and humiliating conditions of Jewish existence, which were directly derived from the nature of the Nazis’ antisemitic ideology and its centrality in shaping the German anti-Jewish policies. In these works, too, Gutman painstakingly fit Jewish resistance in the Holocaust into Jewish history and also into a broad European context. He touched briefly on centuries-long patterns of resistance and organization in Jewish society and, above all, placed the debate about Jewish responses in the Holocaust within the context of discussion of the fate of the other European peoples in World War II. By so doing, Gutman demonstrated his perception of the Holocaust in both its Jewish and its global contexts.

In 2002 Gutman again addressed the need to summarize the issue from a broader perspective. This time, he contended that Jewish resistance was one of many strategies of Jewish survival, one that became realistic only after the information about the murder of the Jews was internalized. By expressing it this way, Gutman defined the uniqueness of the Jewish resistance as flowing not from its value specificities but rather from the totally different reality that the Jews faced relative to other European peoples.

Thus, even though Gutman is often identified with explicit and unequivocal statements about the Holocaust and, particularly, about the Jewish resistance, perusal of his studies reveals the development of his research and the complexity of his responses, which matured over the years. If at first Gutman based himself almost exclusively on the narrative that had been set forth by the members of the wartime resistance and molded by its survivors afterwards, eventually it was he who posited this narrative against reality as he had discovered it. His studies portray Jewish resistance in the Holocaust as a phenomenon shaped both by Jewish history and by the Jewish people’s singular fate under the German occupation, which was defined by unique ideological characteristics; as such, they make a genuine contribution to the discussion of this crucial topic. Obviously, an analysis of Gutman’s historical perspectives on the resistance and many other topics in Holocaust research — tracking the changes that they underwent over time and Gutman’s contribution to the shaping of Holocaust research in Israel and abroad — entails a more thorough investigation than can be performed here. Even this incomplete review, however, shows that there is hardly any topic or controversy in Holocaust research in which Gutman did not play an important part.

Importantly, Gutman rarely stood alone in his principled views. He and Yehuda Bauer usually fought on the same front. Although very different as individuals and as researchers, Gutman and Bauer shared a broad set of basic premises, including the centrality of the antisemitic ideology in the Nazi worldview and the perception of the Holocaust as a constitutive event in both Jewish and modern European history.

As time passed, the research topics, perspectives, and questions that Gutman and Bauer proposed came to be identified with the Jerusalem School of Holocaust research. In fact, however, their way largely shaped the discipline of Holocaust research not only for their many students but also for those who disagreed with them.

Still, these good friends sometimes disagreed publicly. A conspicuous example, a dispute that could originate only in the true friendship and strong love that prevailed between the two, is the way each of them understood the connection — or, as Gutman perceived it, the lack of connection — between genocide and the Holocaust. Gutman categorically opposed viewing the Holocaust as one genocide among many, basing his stance on the unique essence of the Nazi ideology that underlay the murder of the Jews. Bauer sees the matter differently, viewing the Holocaust as the most extreme genocide among all genocides in history. While this principled controversy also oversteps the boundaries of this article, it is an important example of another fundamental characteristic of Gutman’s work: its collaborative nature — among members of the Moreshet Circle, between the Hebrew University and Yad Vashem, and, above all, with Yehuda Bauer. In their collaboration, these two friends exemplified the rabbinical saying, “A knife can be sharpened only on the blade of another.” Thus, it is difficult to assess the ouevre of either of these scholars without relating to his friend, intimate colleague, and sharp-tongued disputant. An additional explanation for Gutman’s ability to maximize his impressive traits was his membership in a research “pair” and his continual discourse with researchers in Israel and abroad. For Gutman, companionship and polemics were important elements of the academic milieu. Perhaps, too, one may discern in them the legacy of a home, a movement, and a magnificent research tradition. But above all, Gutman’s fruitful academic activity was predicated on his towering thoroughness, extraordinary analytic ability, and continual striving for understanding of the Jews’ fate in the Holocaust — as individuals, as a society, and as a community.

Concluding Farewell Remarks

Ahead of the seventieth anniversary of the Warsaw ghetto uprising, I was asked by Yad Vashem to attempt to interview Gutman one more time about the uprising. Gutman remembered all the events from that era in minute detail but struggled to express them systematically, in lucid words. He described the death of Margalit Landau, his friendship with Elek Różanski, and his love of Anielewicz, but his mouth no longer did his bidding. After trying several times, his voice cracked and he said, “They are so alive inside me and I can’t manage to tell their story.”

Gutman was mistaken, of course. He definitely managed to tell their story. In his lengthy, tortuous lifetime, he did much more than write studies that became prime assets and fundamental literature in Holocaust research, lay foundations for the investigation of the Jews’ fate in the Holocaust in Israel and abroad, and establish this important discipline as a constitutive event in Israeli, Jewish, human, and world history. In his books, his lectures, and his lengthy conversations with many interlocutors, Gutman sired generations of students — in academia and elsewhere — and instilled in them love, compassion, and connection with the lost world. It was not only the world of Anielewicz, Korczak, and Ringelblum; it was also the world of his parents, his sister Genia, Margalit Landau, Elek Różanski, and many others. Above all, however, it was his world.

Now Yisrael Gutman — the man of HaShomer HaTza’ir, the Warsaw ghetto fighter, the member of the Jewish resistance in Auschwitz, the professor at the Hebrew University, and the senior scholar at Yad Vashem, has gone to his world, as we say in Hebrew. He has done so in the most elemental and primeval sense of the term. He has gone to the world that he loved, the world that filled his days and troubled his nights; the world that continued to accompany him years after it had gone up in flames. He has gone to his world and he has left us, those who learned from him and loved him, orphaned. Indeed, even at this writing, Holocaust research is wrestling with difficult and important tasks. Yisrael Gutman’s academic legacy and his public and educational activity have left us a solid foundation. Will we — Holocaust researchers in Israel and around the world — have the wisdom to build on that foundation toward the challenge of Holocaust research in the twenty-first century?

Translated from the Hebrew by Naftali Greenwood