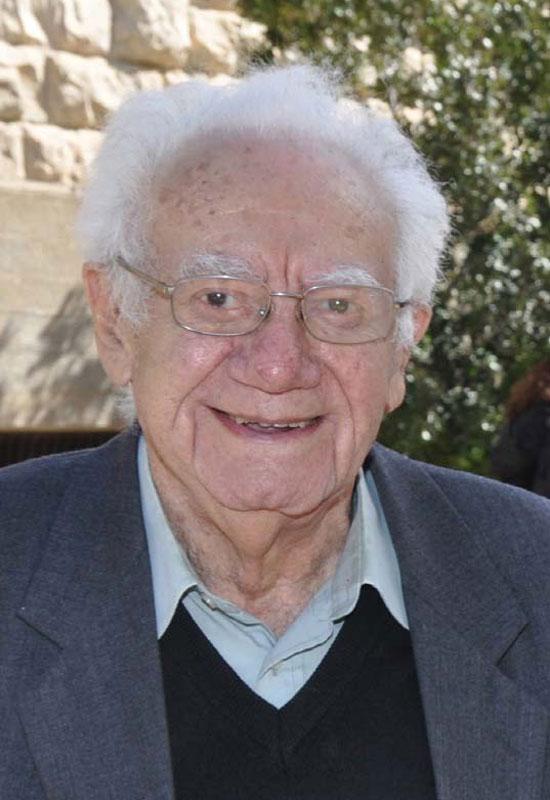

On the day of Yisrael Gutman’s funeral, I bade him farewell in my heart and with private words parted from my friend, who is a decade greater in age and great in wisdom and in magnanimity, with words of deep friendship.

Our paths first crossed, though we were not aware of it initial- ly, seventy years ago, in 1943, in a place that I call the “Metropolis of Death.” Yisrael arrived in Auschwitz by a roundabout route, which had its beginning in the Warsaw ghetto, and I a little earlier from the Theresienstadt ghetto, to the place known as Auschwitz II-Birkenau. We were not yet acquainted at that time. Again, in the death march from Auschwitz, in January 1945, when we were closer physically, we did not meet directly. Yisrael arrived in this country shortly before the establishment of the state and I shortly afterward, and our paths led us to kibbutzim, his in the north of the country, mine a little further south.

We first met face to face in Jerusalem, in the two places that would determine the arc of our lives in Israel: the Hebrew University and Yad Vashem. Or perhaps in the reverse order — at Yad Vashem, as members of the Academic Committee which was established by our common mentor, Shmuel Ettinger; and, almost at the same time, in the Hebrew University’s Department of the History of the Jewish People.

From that time, my life was interlocked with his and Yisrael’s with mine.

But neither of us arrived at the study of that period from the place where we first met. We did not arrive at the study of that period from Auschwitz but from history; Yisrael from the study of court Jews in the absolutist state and from the history of Hassidism, and I from the study of the historical background to the teachings of the Maharal of Prague in the sixteenth century. But both of us did arrive at the study of that period, and subsequently devoted our whole life to it, at the initiative and guidance of our teachers.

While we working on our doctoral theses, in the early 1970s, we shared academic teaching assignments in the first joint monographic class in the department, whose subject was “The Third Reich and the Jews — the Jews in the Third Reich,” a lecture and discussion on sourc- es and historiography. But the crowning peak of our shared academic creation — and I use the word “creation” deliberately — was the three- year cycle of a joint seminar for M.A. and Ph.D. students when we were already professors. Those rounds of lectures and seminar discussions, enhanced by the participation of our friend Prof. Yehuda Bauer and others, spawned the conception that we dared to term the “Jerusalem School of Holocaust study,” or the “Israeli School” of research in this subject. Our point of departure was a critique of the one-dimensionali- ty of the historiography outside Israel, particularly the German histori- ography — though it was of great importance in itself — as it restricted itself solely to the dimension of the persecution and annihilation of the Jews. Whereas our deliberations ranged across the three basic dimen- sions: the regime‘s ideology and policy regarding the Jews; the sur- rounding population’s attitude toward the Jews; and the Jewish society and its leadership.

We discussed a different dimension each year, and with the cooption of our younger friend Richie Yerahmiel Cohen, we considered each dimension at three focal points: Germany and Central Europe under my tutelage; Poland and Eastern Europe under the tutelage of Yisrael Gutman; France and Western Europe under Richie Cohen’s tu- telage. Thus a comprehensive historical picture was formed and the tools were forged for the study of this period as for any other historical period. It was only on the basis of this multidimensional picture, and not a priori assumptions and declarations, that we saw a possibility to discuss and examine the question of the uniquenesss of the Holocaust period. Today, this methodological conception has been accepted or has developed in parallel in a large part of Israeli historiography and in historical research in other countries.

I had the privilege to work alongside Yisrael in some of his finest creative projects, such as the establishment of the Academic Commit- tee of Yad Vashem, his editorship of the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, and the creation of the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem. Our biweekly meetings at Yisrael’s home and our conversations — occasionally a bit vociferous but always creative and productive — about our joint work and problems of research as well as research innovations, which preoccupied us and sometimes disturbed us, were the linchpin of our deep friendship until almost his last days, and were more precious and important to me — and, I believe, to Yis- rael, too — than all else.

As I noted at the outset, the first meeting between us — even if not direct — in the “Metropolis of Death” — Auschwitz — forged a close- ness between us that was always present wherever we met, and it was the only subject which we found no need to talk about between us, ever. And so it shall remain, for all time.

May your memory, Israel, reside in our heart, and your presence abide with us always.

Farewell, my great friend.

Translated from the Hebrew by Ralph Mandel