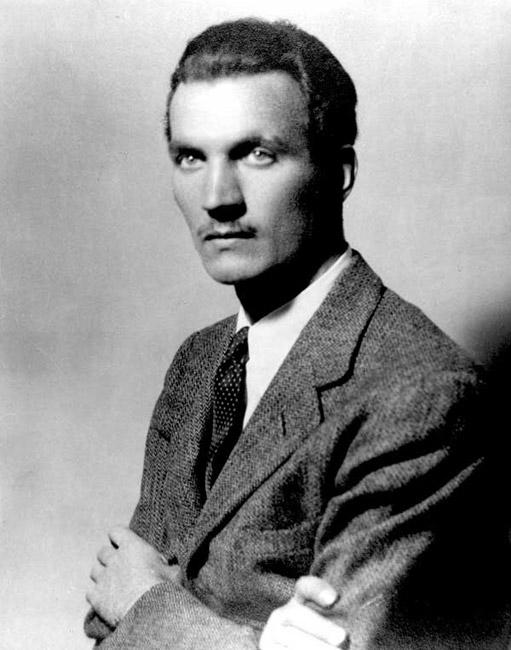

In the past, and now, I heard Jan Karski say, "Jews were abandoned by all world governments but not by all individuals." A Polish Catholic, a Righteous Among the Nations, a World War II hero, an emissary for the Polish underground and the Polish Government in Exile, a professor of political science, Karski's observation grew out of his personal experiences. (Jan Karski, Personal communication, 1999). Mixed in with Karski's wartime political and humanitarian preoccupations was a strong opposition to the Nazi policies of the biological annihilation of the Jewish people. He tried to stop it by alerting the leaders of the free world to the systematic murder of the Jews.

In preparation for one of his illegal transatlantic journeys, Karski met with Jewish leaders in Poland and agreed to deliver their messages to the Allies and to others whom they saw as influential in the free world. In addition, with the help of the Jewish underground leaders, Karski smuggled himself twice into the Warsaw Ghetto, to gain first hand knowledge of the Jewish plight. Then, for a report of another phase of Jewish destruction, dressed as a guard, Karski entered Izbica, which served as a looting, murdering and holding camp for Jews destined for the death camp, Belzec. Not only was Karski risking his life through these visits, but he endangered his psychological well being as well. Confronted by the camp's degrading conditions, he suffered a nervous breakdown which only magnified the threats to his life. (T. Thomas Wood and Stanislaw M. Jankowski, Karski, How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1994), pp. 124-130).

Later, in the free world, Karski met with influential leaders including President Roosevelt and the British foreign minister, Anthony Eden. Karski's reports about the Jewish plight and the messages from the Jewish leaders that inevitably pleaded for help fell on deaf ears. For the Allies, as for other governments, the German systematic murder of the Jews was definitely not a priority. These personal contacts with high ranking governmental officials must have convinced Karski that the Jews were abandoned by all world governments.

Karski's intellect and humanitarian spirit taught him some other lessons. He believes that even though in wartime Europe the murderers of Jews by far outnumber those who wanted to save them, it is counterproductive to concentrate only on the murderers of Jews and ignore the minority that was determined to save them. This assertion Karski explains is based on two reasons. First, because it is historically untrue. Thousands of Christians tried to save Jews and were ready to die for them. Some did. Second, because this kind of an emphasis perpetuates the idea that "everybody hates the Jews". Not everyone hates the Jews. Christian rescuers felt that the Jews were valuable enough to risk their lives for them. In short, it is both historically incorrect and psychologically unhealthy to concentrate on the idea that no-one wanted to save Jews. (Jan Karski, Personal communication, 1999).

It is generally agreed that in addition to the more than 16,000 Christians, recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations, many more thousands of Christians tried to rescue Jews but for many reasons remain unknown. While the exact number of those who risked their lives to save Jews, for obvious and not so obvious reasons, will probably never be know, knowledge about the exact numbers is less important than insights about this kind of behavior. Such insight carries a promise of positive lessons.

Under the German occupation the appearance of Christians who selflessly risked their lives to save Jews signaled an opposition to the Nazi policies of Jewish destruction. Aid to Jews was illegal and endangered the lives of the rescuers and their families. And yet, each country under the German occupation had some individuals who endangered their lives for Jews. Significantly, too, of the Jews who illegally survived in the Christian world, practically all had benefited from some kind of aid. Moreover, my research is based on evidence from 309 Jews who survived the war by hiding or passing in the forbidden Christian world and who mention 565 Christian rescuers who tell that over 80 % of their protectors offered aid without any expectation of concrete rewards. (I, myself, benefited from the help of Christian rescuers who were motivated by profit. See: Nechama Tec, Dry Tears, The Story of a Lost Childhood, New York: Oxford University Press, 1982). To be sure, there were some who saved Jews for money but they made up less than 20 %. As a group, Christian rescuers who tried to save Jews without motivations for personal gains fit into the definition of altruistic rescuers. (For a comparison of altruistic and other kinds of rescuers, see: Nechama Tec, When Light Pierced the Darkness, Christian Rescue of Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland (New York, Oxford University Press, 1986) pp. 70-109).

Concentrating on altruistic rescuers, what characteristics did they share? Who among the non-Jews was likely to try to overcome the many barriers and rescue Jews? Who was most likely to stand up for the persecuted Jews, traditionally viewed as "Christ-killers" and blamed for every conceivable ill?

If we were a part of a group of people that included altruistic rescuers, we could not distinguish these rescuers from the rest of the group. Traditional ways for placing people into certain categories are of no help. When I compared large numbers of non-Jewish rescuers in terms of social class, education, political involvement, degree of antisemitism, extent of religious commitment, and friendship with Jews, they were very heterogeneous. Some of them came from higher, some from lower classes. Some were well educated, while others were illiterate. Comparisons in terms of religious and political affiliations also show much diversity. From these comparisons I had to conclude that conventional ways of categorizing people do not predict rescue.

A few examples of the Righteous Among the Nations illustrate their diversity. Returning to Jan Karski, a Righteous and an honorary citizen of Israel, came from a socially privileged background. As a young university graduate he entered the Polish Foreign Service and was an aspiring young diplomat. His mother instilled in him tolerance for people who differed from him; this included Jews. The idea of social justice was a part of his upbringing and it meant standing up for the less fortunate. Catholicism played an important part in Karski's life. But, religious practice did not interfere with the high value placed on independence.

In contrast, Stanislawa Dawidziuk (Szymkiewicz), a young factory worker in Warsaw, came from a poor working class family. She had only a few years of schooling and completed her elementary school education after the war. Under the German occupation Stanislawa shared a one-room apartment with her husband, a waiter, and a teenage brother, an orphan. In 1943, at the husband's request she agreed to add to her cramped quarters a woman whose looks betrayed her Jewish background. The woman, Irena, was brought by Ryszard Kaminski, a Polish policeman, who begged Stanislawa's husband to keep her just for one night. Next day Kaminski could not find a new home for Irena. Irena's single-day stay soon soon stretched into weeks. Stanislawa's husband refused to continue risking his life for their guest. He became adamant and demanded that his wife dismiss Irena. Stanislawa objected. She knew that Irena's appearance in the street would lead to her death. Eventually, in protest, Stanislawa's husband stormed out of the apartment, never to return.

In his absence Stanislawa gave birth to a boy. She arranged a special place behind a movable closet for Irena. Kaminski continued to visit, supplying them with modest provisions of food. Despite serious threats and several close calls, Stanislawa Dawidziuk insisted that Irena stay on. When, after the Warsaw uprising, in 1944, the Germans were evacuating the Polish population, it was rumored that mothers of small children could stay on. Because Stanislawa worried about Irena's "Jewish looks", she bandaged her face, pretending that it protected her from a toothache. Stanislawa insisted that Irena should claim the baby as her own. She felt that by staying in the apartment with the baby Irena would be safer. In the end, all were given permission to stay on.

Stanislawa did not quite fit into her antisemitic environment. She was not concerned with what others thought about her. She was surprised that I was interested in her story. Saving Irena was just something she felt she ought to have done. She insisted that she could not have acted in any other way.

After the war Irena emigrated to Israel where she died in 1975. Stanislawa Dawidziuk remained in Poland, and in 1981 she was recognized by Yad Vashem as a Righteous Among the Nations.

Coming from a different background, Marion van Binsbergen (later Pritchard) somehow resembles Stanislawa Dawidziuk. Marion was 20 years old when the Germans occupied her native Holland. She was the daughter of a prominent judge and an English mother, both of whom instilled in her tolerant values, a keen sense of justice, and a fierce independence.

Appalled by what she saw around her, from 1942 till 1945, van Binsbergen devoted all her energies to anti-Nazi activities, that involved the saving of Jews, most of whom were young children. She would locate hiding places, help them move, and provide them with food, clothing and ration cards. She also lent moral support to the Jewish fugitives as well as the families who hosted them. One extraordinary way in which she saved Jewish lives was by registering newborn Jewish babies as her own. She managed to register several of these children within a span of five months.

Then van Binsbergen (Pritchard) was asked by a Dutch resistance leader to find a hiding place for a Jewish friend with three young children. When she could not find one, she moved with the fugitives into a small house in the country. There she was soon confronted by a Nazi collaborator, who was about to discover the hidden Jews. To prevent this from happening, van Binsbergen shot the intruder though she had never fired a gun before. She continued to take care of this family for two years, until the end of the war. About her rescue of Jews, Marion talks in a matter of fact way.

Marion van Binsbergen Pritchard has received the Yad Vashem Medal of the Righteous Among the Nations and became an honorary citizen of the State of Israel. (Based on Nechama Tec, 'Righteous Among the Nations' in The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, to be published by Yale University Press).

As I mentioned earlier, comparisons of large numbers of rescuers in terms of conventional ways of categorizing people, such as class, education, religion, politics and more, show great difference. When, however, these individuals are examined at close range, a cluster of shared characteristics and conditions emerge. One of these characteristics, sometimes referred to as individuality, separateness, or marginality, suggests that the rescuers did not quite fit into their social environments. Not all of them were aware of this tendency, but whether they were conscious of it or not, the individuality of these rescuers appeared under different guises and was related to other shared attributes and conditions.

Being on the periphery of a community means being less affected by the community's expectations and controls. Therefore with individuality comes freedom from social constraints, and a higher level of independence, offering an opportunity to act in accordance with personal values and moral precepts even when these are in opposition to societal demands.

The rescuers I studied seemed to have had no trouble talking about their self-reliance and their need to follow personal inclinations and values. Nearly all defined themselves as independent. They were motivated by moral values that do not depend on the support and approval of others but on their own self-approval. They are usually at peace with themselves and with their own ideas of what is right or wrong. One of their central values involved a long-standing commitment to protect the needy. This commitment was often expressed in a wide range of charitable acts extending over a long period of time. Risking their lives for Jews during World War II fits into a system of values and behaviors that had to do with helping the weak and the dependent.

This analogy, however, has its limitations. Most disinterested actions on behalf of others might have involved extreme inconvenience, but only rarely would such acts suggest that the givers had to make the ultimate sacrifice of their own lives. For these righteous rescuers, the war provided a convergence between historical events demanding complete selflessness and their predisposition to help. People tend to take their repetitive actions for granted. What they take for granted they accept, and what they accept they rarely analyze or question. Therefore the constant pressure of, or familiarity with, ideas and actions does not necessarily translate into knowledge or understanding. On the contrary, easy acceptance of customary patterns often impedes understanding.

A related tendency is to view the actions that one habitually repeats as ordinary, regardless of how exceptional they may appear to others. And so the rescuers' history of helping the needy may have been in part responsible for their modest appraisal of their life-threatening actions. Rescuers seem to have seen in their protection of Jews a natural reaction to human suffering. Many insisted that saving lives was not remarkable and was unworthy of special notice.

Given such matter-of-fact perceptions of rescue, it is not surprising that aid to Jews often began spontaneously and without planning. The unpremeditated start underscores the rescuers' need to stand up for the poor and helpless. This need to assist those in distress overshadowed all considerations of their personal safety and that of their families. Most protectors, when asked why they had saved Jews, emphasized that they had responded to the persecution and the suffering of other human beings, and said that the fact that the sufferers were Jews was entirely incidental to their impulse to act. A minority of rescuers claimed to have helped out of a sense of Christian duty or in protest against the German occupation.

This ability to disregard all attributes of the needy except their helplessness and dependency points to universalistic perceptions. The compelling moral force behind the rescuing of Jews, as well as the universal insistence that what mattered were the victims' dependence and unjust persecution, combined to make such actions universalistic. To recapitulate, Christians who selflessly risked their lives shared, closely related, six characteristics and conditions: individuality or separateness from their social environment; independence or self-reliance; a commitment to helping the needy; a modest self-appraisal of their extraordinary actions; unplanned initial engagement in Jewish rescue; and universalistic perceptions of Jews as human beings in dire need of assistance. The close interdependence of these six characteristics and conditions offers a preliminary explanation of altruistic rescue of Jews by Righteous Christians. (Much of this discussion is taken from Chapter 10, 'A New Theory of Rescue and Rescuers' in my book When Light Pierced the Darkness, pp. 150-183).

Nazi policies of Jewish biological destruction led to extreme cruelty, devastation, and evil, and much less frequently to expressions of extreme goodness epitomized by the Christian rescuers of Jews. The selfless sacrifices of these Christian rescuers may serve as a model for others to imitate their paths now and in the future.