This topic is very complex, with many different factors significantly affecting the rescue of Jews. With all the distress, horrors and deaths by the Jewish population in occupied France, their suffering was less severe than in most other occupied countries. When the Germans occupied France in June 1940 and the truce between Germany and France was signed, the country was divided into a number of areas, the most significant of which were the German-occupied area in the north and west, and the southern area, under the rule of the Vichy government, which remained free of any German military presence until 10 November 1942.

During the four years of occupation, the areas of Jewish concentration in France underwent many changes. Close to 150,000 people fled south from the German invasion, dispersing throughout hundreds of towns and villages. They were joined by some 40,000 Jewish refugees from Belgium and Holland. The government, headed by Marshall Pétain, concentrated 40,000 Jews from Germany, Austria and Moravia into detainment camps, mostly in the southwest, at the foot of the Pyrenean mountains. From November 1942 - September 1943, the area from the Alpine border of Switzerland down to the Mediterranean coast – including the city of Nice – was under Italian occupation. The Jews there merited protection by the occupying powers, which prevented the French and the Germans from interfering and enacting anti-Jewish decrees.

In 1940, practically nobody thought of resisting the ruling powers and going underground. The French population as a whole, including the Jews, put their faith in the leadership of Marshall Pétain. The first decrees – which included the concentration of citizens from hostile nations in camps, forbade their employment in public office, the media and free trade, and legislated discriminatory policies stripping them of their French citizenship – were considered comparatively moderate and did not especially worry the veteran Jewish community, citizens of the state. In fact, these policies were even welcomed by most of these Jews, who viewed them as proof that the French government would protect its Jewish nationals. The general sentiment was to stand firm until the storm passed, and not to become entangled with the law. The accepted Jewish response was thus obedience, submission and acceptance. When the decree for a Jewish census was publicized, they all complied, and had their identity cards and ration books stamped with “Juif.” Moreover, almost no Jews refrained from wearing the yellow star, decreed only in the north and west on 7 June 1942.

A few individuals, who, in opposition to most of French Jewry, were not prepared to accept the ruling decisions and comply with the discriminatory laws, began already in 1940 to lay the foundations of an organized underground. As the anti-Jewish decrees progressively worsened, these people resolved to thwart their enactment. They soon developed into organized underground units, and the number of Jewish joining them steadily increased. Some of them formed partisan groups, but most worked in rescue activities. The Jews in these areas were aware of the need of a unique Jewish fight, different in purpose from the battle being fought by the French underground.

The French resistance worked to free their motherland from the occupying forces. The French partisans, including the Jews who worked for them, believed that on Victory Day all the anti-Jewish decrees would be completely annulled and they would no longer be persecuted. The rescue of Jewish citizens from the hands of the Germans was therefore viewed by the resistance as a humanitarian act, to be carried out after the motherland was completely liberated. They ignored those Jewish underground activists who feared that not a single Jew would survive to celebrate victory. These activists therefore decided to act in haste to save the Jews. They set up underground Jewish organizations that placed saving lives as their top priority. The unique Jewish resistance was made up of different groups that strengthened the Jewish population’s religious, spiritual, cultural and political lives, distributed vital sustenance for the needy, worked to liberate Jews from detention and deportation, and participated in the armed battle of the partisans.

The chances of rescue were obviously defined by the unique situation in France as well as the existence of a French regime that collaborated with the Germans. This created a complicated reality, with both positive and negative elements. Much rested on the willingness of the French government to answer the demands of the occupiers. The logic behind the collaborative policies of Pétain and his followers was to ensure the place of France as a sovereign power in the new world order planned by German after its victory in the war. However, as this victory became more unlikely, the Vichy government became less and less willing to work for the Germans. As such, during 1943 the wave of arrests of Jews by the French government came to a dramatic halt.

The Jews were not concentrated in ghettos or a delineated area. They were scattered throughout many districts, mostly in the south. This dispersal dented the ability of the Jewish movements and organizations to bring their comrades news or instruction, but also reduced the chances of their discovery and detention. In order to carry out an arrest, the government officials had to find and identify the accused. A Jewish family that had left its home could no longer be harmed by the police, unless it fell victim to informants. The law did not limit the freedom of movement of Jews with French citizenship, and any foreign Jew who managed to obtain forged papers could move around as he wished.

In general, the French population was passive regarding the occupation. Not so the underground organizations, though their people displayed some apathy regarding the fate of the Jews. Nevertheless, when the mass arrests and deportations began, many in France became willing to help the Jews, including certain officials and policemen who worked systematically to torpedo the anti-Jewish decrees, even though they knew this would put their own lives in danger.

One of these figures was Camille Ernst, general secretary of one of the districts of Montpellier. Among his duties, Ernst headed the local police force. He gave advanced warnings of impending arrests, and initiated special edicts that allowed foreign Jews to stay in his district. Ernst also facilitated the rescue of hundreds of Jewish children from the detention camps of southwestern France, as well as their absorption into his district. Later, Ernst cooperated with Jewish rescue organizations, which organized various hiding places. Ernst was willing to help Jews for no gain, and Jews in distress continued to turn to him for vital aid. Ernst was eventually discovered by the Vichy government and ordered to give a full account and justification of his actions. When he was unable to explain the failure of the actions to intern Jews, he was sent to the Dachau concentration camp. Ernst returned to France in 1945.

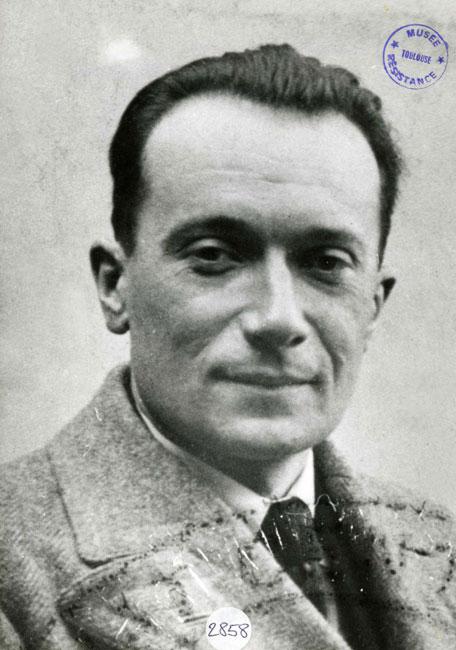

From the early 1930s, Jean Phillipe filled a number of roles in the army and police force. In 1942, he was appointed chief of police of the 9th arrondissement in the city of Toulouse. At that time, Phillipe was active in the underground network, preventing the arrest of many underground activists. In January 1943, Phillipe received an order to submit a list of all the Jews living in his arrondissement. He refused, instead submitting a letter of resignation to his superiors. In his letter he strongly condemned the collaborative policies of the Vichy government, and added that he was unable to serve a regime that did not, in his opinion, represent the ideals of his French motherland, to which – and only to which – did he swear allegiance. Phillipe stressed that the Jews had a right to live exactly as all other citizens. After his letter of resignation was submitted, Phillipe went underground, but was arrested by the Gestapo on 28 January 1943. He was investigated and tortured, and then imprisoned in Germany. On 1 May Phillipe was executed. Lucien David Fayman, active in the Jewish underground, later related that as chief of police, Phillipe helped obtain forged documents, signed and stamped by the police, which were given to young Jews escaping to Switzerland or to hiding places within France.

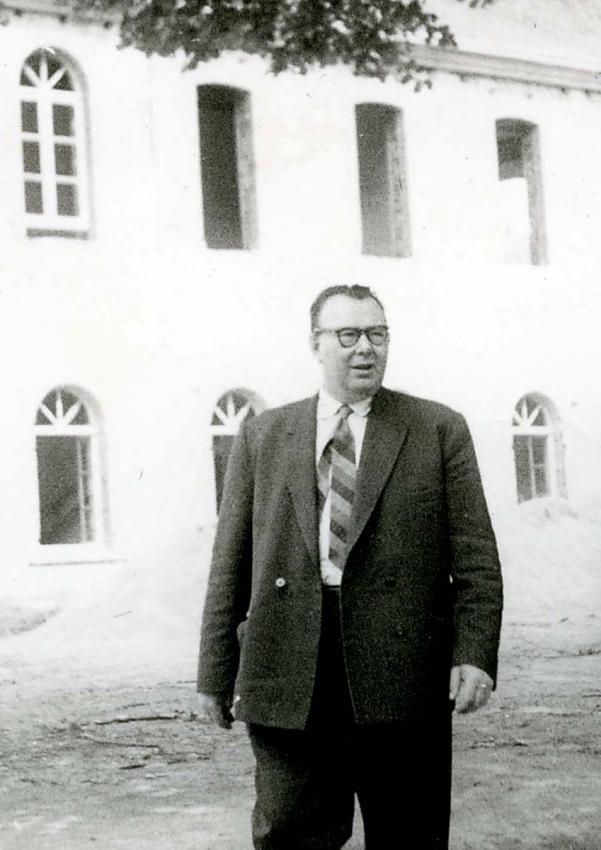

Another example of high-level officials who helped rescue Jews and foil the policies of the regime was Gilbert Lesage. As a young man, Gilbert Lesage was a conscientious objector. He was an activist with the Quakers, who sent him to Germany in the 1930s. Even at that early stage, he was sensitive to the fate of the persecuted Jews. In the summer of 1940, Lesage offered his services to the Vichy regime and was appointed head of the SSE (Service Social des Etrangers, the social-service agency for aliens). In August 1942, when the authorities in southern France began to round up Jews and turn them over to the Germans, Lesage was placed in charge of selecting Jews for deportation, according to police secretary-general, René Bousquet’s instructions. Lesage disobeyed his orders and clandestinely warned Jewish and other rescue organizations of impending raids, thus making it possible to hide most of the children consigned to deportation. When Bousquet eliminated all exemptions from deportation, Lesage ignored this order as well and sent the selection officers an instruction sheet exempting everyone under the age of sixteen. He personally directed the selection process at a camp near Lyons and freed 108 Jewish children. This method was used in other places where Jews were concentrated. Police officers reported this to Bousquet, and Lesage was investigated on suspicion of foiling “operations meant to concentrate several types of aliens.” Lesage was arrested on April 8, 1944, and the SSE was shut down in June. Lesage remained in prison until the liberation of France. He belonged to the group of senior Vichy officials who courageously used their power to foil the authorities’ policies.

The plague of informants pervaded France, although the treatment of their victims was in most cases careless and inconsistent. However, any citizen caught on suspicion of sheltering Jews could expect severe punishment. Such was the fate of Lucien Bunel and his charges, all victims of informants.

Bunel was a priest in the Carmelite order in the small town of Avon, close to Fontainebleau. His church opened its gates to refugees persecuted by the Germans. Among those hiding there were three Jewish students who lived and learned in the boarding school under false identities. In addition to these youngsters, Father Bunel took on Lucien Weil as a teacher who, under Vichy laws, had been fired from his position as a natural science teacher in the Fontainebleau school. On 15 January 1944, as a result of detailed and precise informing, Gestapo men appeared within the college gates and with no prior warning entered the classrooms where the Jewish children were studying, arresting them on the spot. The three students were sent to Auschwitz were they were murdered, while Father Bunel was arrested and the college closed down. On the same day Lucien Weil was also arrested, along with his mother and sister in their house in Fontainebleau, and they were sent to Auschwitz. Father Bunel was imprisoned in Fontainebleau, and from there deported to Mauthausen, and then on to other concentration camps in Germany. The inhuman conditions of these camps led to his death a few days after he was finally released. One of his boarding school students, Louis Malle, later a famous film director, produced the movie Au Revoir Les Enfants based on his memories of the tragedy of Father Bunel and his Jewish charges.

No less moving is the story of Dr. Adelaide Hautval, a psychiatrist who lived in a Vichy-controlled area of southern France. In April 1942, Hautval was told of the death of her mother, who had lived in occupied Paris. Wishing to attend her mother’s burial, Hautval asked the German authorities for permission to enter the Occupied Zone. They refused and Hautval decided to risk crossing the Demarcation Line. The attempt failed, and Dr. Hautval was captured by German police and transferred to the prison in Bourges. In June 1942, Jewish prisoners wearing the yellow patch began to arrive at the prison. Hautval remonstrated with the prison guards about the deplorable treatment of the Jewish prisoners, declaring, “They are human beings just like we are.” The guards replied, “From now on, you shall be treated like the Jews.” In January 1943, Dr. Hautval was transferred, with another two hundred French women prisoners, to the Birkenau death camp. Hautval, a devout Protestant, was housed with five hundred Jewish women prisoners, and was nicknamed “the saint.” She applied her medical knowledge to treat Jewish prisoners who had contracted typhus, secluding them in a separate part of the block, in order to prevent contagion. Hautval, employed as a physician by the camp commander, refrained from reporting the prisoners’ illness and thereby spared them immediate death. She treated Jewish patients with boundless dedication, and her gentle hands and warm words were of inestimable value to Jews in the hell of Auschwitz. “Here,” she said, in words engraved on the prisoners’ memory, “we are all under sentence of death. Let us behave like human beings as long as we are alive.”

Eventually Dr. Hautval was transferred to Block 10 of the Auschwitz I camp, where medical experiments were performed. She was put to work identifying the early manifestations of cancer in women. Dr. Hautval quickly discovered that the project entailed inhuman experiments, performed without anesthesia, on Jewish women prisoners. She told her superiors that she would not participate in these experiments. When forced to assist in the surgical sterilization of a young woman from Greece, Dr. Hautval announced that she would never again attend such a procedure. She was sent back to her barracks in Birkenau.

Another escape route for Jews entailed crossing the border to neutral Switzerland or Spain, open, at least partially, to the absorption of Jewish refugees. However, the illegal crossing of the border was a complicated and dangerous task, made possible only with the help of the local population. The story of the Catholic priest Raymond Boccard exemplifies this kind of rescue.

Boccard worked as a gardener in the town’s school close to the French-Swiss border. He and four other priests who studied in the school helped hundreds of people steal across the Swiss border, thus saving their lives. Among those aided by the priests were a large number of Jews. Boccard lived in the room in the attic of the school, from which he could view the German border guard patrols. The wall of the institution’s garden touched the border, and the priests’ friends would stand next to the wall with a group of people wishing to cross. Boccard would wait until the German patrol passed, and then wave his beret, the agreed sign to jump over the wall. The endeavor had to be carried out carefully, in no more than two-and-a-half minutes. Even if the attempt succeeded and the refugees avoided the German forces, they were sometimes caught by Swiss border guards. When they were returned to the French side of the border, Boccard waited for them and brought them to the school. They would stay the night and the next day he would accompany them to the train station.

Many persecuted Jews found shelter in a few mainly protestant areas in France. One example was the mountain village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon; over 50 of its residents have been recognized as Righteous Among the Nations. From November 1942 until liberation, the owners of the town’s hotel, the Mays, turned their home into a temporary refuge for dozens of Jews, until they could find a permanent hiding place in other houses in the village and surrounding areas. The hotel became the nerve center of the rescue activities of village, and thanks to the contacts the Mays had with the local police, they received advance warning of planned raids by the Gestapo and local militias. When a warning came, the Mays and two of their children went to every hiding place in the village and surrounding areas, warning the survivors. Anyone in danger of deportation fled to the forest until the searchers were over. The Germans knew the village was a center for the French underground and therefore conducted many raids in the area.

Rescuers of Jews came from all strata of the population, many of whom acted spontaneously and remained anonymous. Jeanne Vernusse lived in the outskirts of the town of Clermont-Ferrand. Vernusse worked as a saleswoman in a ladies’ clothes shop in the town and lived in her mother’s home. One day in 1942 her friend introduced her to a Jewish man who lived with his five-year-old daughter in a small room above a lively coffee shop. Two days earlier, his daughter had been the victim of public harassment, and the father feared she would be arrested and sent east. The man was separated from his wife, who was hiding with his second daughter, aged four. When she heard the story, Vernusse immediately took his daughter to her home where her mother also received her warmly. When it turned out that the other daughter was also in danger, Vernusse and her mother decided to take her in as well. Vernusse passed the girls off as her nieces, registering them under the name of Vernusse in the local school. Later, the two Jewish girls testified that Vernusse and her mother were poverty-stricken. The mother did not work and Vernusse earned little from her employment as a saleswoman, but “they took food out of their own mouths so that we would have what to eat.” When rumors of searches for Jewish children spread in the town, Vernusse decided to take the girls out of school and from then on, when she returned from work each day, taught them reading, writing and arithmetic. When her neighbor threatened to reveal the true identity of the Jewish girls, Vernusse was forced to find them refuge with a family of artisans in the small village of far off in the mountains. The girls stayed in their new hiding place until liberation.

These are but a few personal stories of the rescuers of Jews in France during the war. Though the percentage of rescuers out of the total French population was small, many provided at least passive support to such activities in their areas. Even those who were not willing to endanger themselves and extend a supporting hand to the Jews refused to inform on those hiding with their neighbors. The rescuers, Righteous Among the Nations – and other rescue organizations mentioned above – played a decisive part in foiling the Final Solution in France. While the French resistance movements did not concern themselves with the fate of the Jews other than the fact that the liberation of the motherland would put an end to Jewish persecution, the rescuers acted out of humane, moral and religious values, and consciously or subconsciously adhered to the tenet that anyone who saves a life saves an entire universe.