Berthold Beitz, one of the leading industrialists in postwar Germany, was born on September 26, 1913 in Zemmin/Pommerania. Many years after the war, reflecting on his experiences in Boryslaw during the German occupation, Berthold Beitz, director-general of the Krupp Corporation in Essen and an honorary member of the German Olympic Committee, was at pains to clarify that his motives had in no way been grounded in any kind of principled political opposition to National Socialism: That was no anti-Fascism, no resistance [Widerstand]. We watched from morning to evening as close as you can get what was happening to the Jews in Boryslaw. When you see a woman with her child in her arms being shot, and you yourself have a child, then your response is bound to be completely different.“

In fact, though he never engaged in active political opposition to Nazism, Beitz‘s help to the Jews of Borsyslaw directly challenged the most crucial ideological fixation of the regime. In this sense, it may be categorized as a higher form of resistance to Nazism.

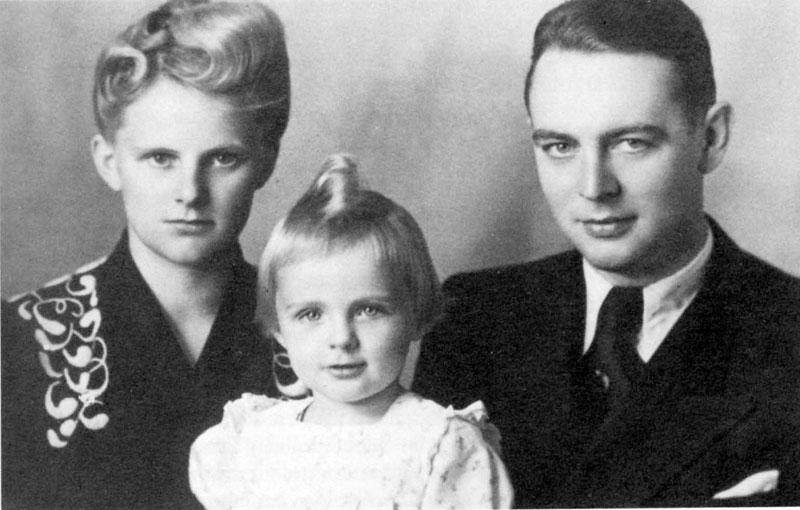

Like his father, Berthold studied to be a banker. In April 1939, at the age of twenty-five, he was engaged by the renowned Royal Dutch Shell Oil Company in Hamburg. It was as a result of the expertise he had acquired in the strategically important oil industry that Beitz could have his military service deferred and receive a wartime commission as the business manager of the Beskidian Oil Company - later renamed the Carpathian Oil Company—at Boryslaw in eastern Galicia.

Both Boryslaw and the nearby regional town of Drohobycz were important oil-industry centers with relatively large Jewish populations. Jews—chemical engineers, laboratory assistants, mechanics, auditors, businessmen, and also unskilled laborers—made up a large part of the local task force, which was taken over by the Carpathian Oil Company after the German occupation of Boryslaw and Drohobycz on July 1, 1941. In order to protect the indispensable Jewish employees from the sporadic anti-Jewish raids carried out by the SS and their Ukrainian collaborators, the Carpathian Oil Company, like other German firms in the surrounding region, housed them and their families in segregated work camps. For their protection they had a special badge sewn on their chests with the letter “R” inscribed on it. (The “R” probably signified Rüstungsarbeiter, or armaments’ worker).

Arriving in Boryslaw at the beginning of July 1941, in the wake of the German troops, Beitz witnessed first hand the atrocities perpetrated against the helpless Jewish population. In the course of the so-called “Invaliden-Aktion” on August 7, 1942, the SS evacuated the Jewish orphanage of Boryslaw in an indescribably brutal manner. Beitz, who had been alerted by the Schutzpolizei (police constabulary), watched as infants were thrown out of windows and children dragged out of their beds were driven barefoot in the middle of the night to the railway station.

As the influential business director of the strategically vital oil company, Beitz had connections to the more important Nazi functionaries in the region. He was notified in advance of impending anti-Jewish “actions” and had the right to inspect the Jews who had been rounded up at the Umschlagplatz (transfer point), to pick suitably qualified workers, and to insure that none of his own workers were included in the transports to the death camps. Thus, in August 1942, he extricated 250 Jewish men and women from the transport train to the Belzec extermination camp by claiming them as “professional workers.”

However, numerous eyewitness reports leave no doubt that the twenty-seven-year-old director of the Carpathian Oil Company by no means limited himself to workers who could expedite the production of oil for the German war machine. The Jews that he rescued from deportation included many unqualified workers, often in poor physical condition, who could not, by any stretch of the imagination, be described as “professionals” or indispensable to the oil industry. Beitz placed himself at considerable risk by passing on to his Jewish confidants inside information of impending “actions.” Both he and his wife concealed Jews “on the run” in their own home, thus exposing themselves to denunciations.

Ironically, the only time the Gestapo actually started an investigation against him, was after a “false scent.” Early in 1943, the German police arrested on the train to Hungary two Jewish girls with forged permits for “Aryan” workers signed by Beitz. It appears that the two girls belonged to a Jewish underground group led by Zwi Heilig. The organization had stolen blank forms of permits for “Aryan” workers from Beitz’s office in order to smuggle its members across the Hungarian border. Heilig, who survived the war, later testified about the consternation of the Jewish workers at the Carpathian Oil Company who had heard rumors about a noisy altercation that their protector had had with Gestapo officials. Nevertheless, Beitz managed to survive the incident and remained at Boryslaw until March 1944, when he was drafted into the army.

Beitz’s nomination as Righteous Among the Nations, strongly supported by the great majority of survivors from Boryslaw and its environs (many of whom had kept in contact with their rescuer after the war ), was hotly contested by a small minority. The opponents argued that the primary motive of the former director of the Carpathian Oil Company at Boryslaw was to increase the production capacity of the German armaments industry, that he had acted only in order to line his own pockets with money and, finally, that he had not put himself at any substantial risk in rescuing Jewish workers for the German oil industry.

Yet none of these allegations appears to be borne out by the facts of the case. There seems to be more substance to the claims concerning the evidence that Beitz gave in 1952, and again in 1966, in favor of Fritz Hildebrand, the notorious SS commandant of the forced-labor camp. In his 1966 testimony in Bremen, Beitz claimed that Hildebrand “shut both his eyes” to the forbidden employment of Jews in the company’s offices and elsewhere. However, controversial as they may be, Beitz’s postwar testimonies cannot undo the significance of what he did during the Holocaust.

On October 3, 1973, Yad Vashem recognized Berthold Beitz as Righteous Among the Nations. On 5 February 2006 Yad Vashem recognized Else Beitz as Righteous Among the Nations.