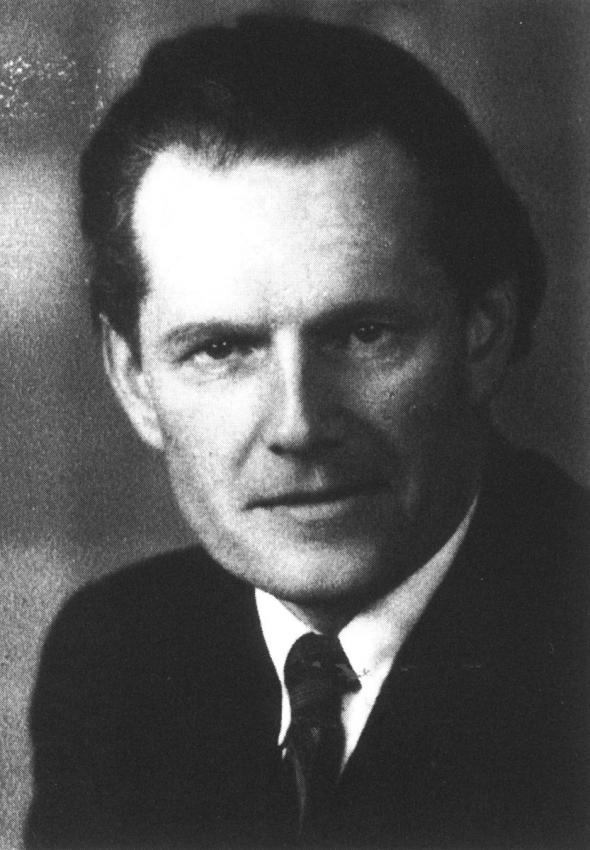

Hans Calmeyer was born on June 23, 1903 in Osnabrück. The son of a judge, he was known in his native city to be an eminent lawyer. Unidentified with any particular political party, he had a private practice with only two employees, one of whom was a Jewish woman. When the NSDAP rose to power in January 1933, Calmeyer was forbidden to practice on suspicion of being “politically unreliable” and engaging in “communist intrigues” (Umtriebe). The latter accusation was based on the fact that Calmeyer had defended communists in court from time to time. While his political worldview was more leftist oriented – although by no means extreme – this was sufficient for the new rulers to brand him as untrustworthy. In May 1940 Calmayer arrived in the Netherlands with the invading forces. A hometown acquaintance offered him to join the occupation administration.

In Nazi worldview of races, the Dutch were considered pure Aryans. The need to purify the Netherlands of alien races therefore became a paramount goal, and a special office, which Calmayer was to head, was established in order to examine doubtful cases so as to decide whether they were to be considered Aryans. One of the main tasks of this office was to examine people of Jewish origin. When in January 1941 Dutch Jews were ordered to register with the authorities, even those who were half or quarter Jews were included in the list. Unaware of the fate that awaited them, Jews abided by the edict. However when the deportations began and the significance of being registered as Jews was revealed, these and others applied to Calmayer’s office in order to change their classification.

From the moment Calmeyer began his job, on March 3, 1941, he realized that it afforded him the – albeit risky – opportunity to help Jews. At the same time, Calmeyer also realized that he would have to act with the utmost care in order to avoid arousing any suspicion within the fiercely antisemitic environment in which he was working. Only to a few carefully selected and reliable confidantes, such as the Dutch lawyer Y.H.M. Nijgh did he voice his profound loathing of National Socialism in general and the persecution of the Jews in particular.

Even so, he avoided any personal contact with lawyers who approached the Generalkommissariat on behalf of Jewish clients, so he would not be suspected of friendliness to Jews (Judenfreundlichkeit). Neither did he ever attempt to intervene personally on behalf of Jews – with the exception of one particular case, his former legal assistant – an attempt that failed.

His first move to shield his department from hostile interference was the choice of his coworkers. His direct assistants were the lawyer Dr. G. Wander, Heinrich Miessen, a war-invalid and Sippenforscher (genealogical researcher), and, eventually, the young Dutch lawyer J. van Proosdij--all of whom were opposed to the Nazi regime. His office workers, including the secretaries in his department, were also trustworthy. Calmeyer's bureau was a singular anti-National-Socialist “cell” within the occupation government. Calmeyer's second step was the creation of a passage through which Jews might be assisted in escaping from the German registration trap. According to the German Nuremberg Laws, membership in a Jewish community was considered proof of a person's Jewishness. It was a praemissio juris et de jure, i.e., a judicial proposition impervious to proof of the contrary. Only the Führer himself was capable of invalidating a person's Jewish descent, or, at any rate, deciding that his Jewish background need not be held against him.

As early as March 24, 1941, Calmeyer argued, in a memorandum, that, within the framework of the racial laws, membership in a religious community could not possibly be regarded as a decisive factor. He also pointed out that, in practice, the application of this ruling was stricter in Holland than in Germany, due to the absence in the Netherlands of a supreme authority to whom problem cases could be referred. Calmeyer cited several examples of the resulting quandaries, including that of a prominent member of the Dutch National Socialist Party (N.S.B.) who had a Jewish grandfather, and the influential banker Pierson, whose grandmother had been of Portuguese Jewish descent, but who, as a child, had been taken out of the Portuguese-Jewish community.

Consequently, Calmeyer proposed that, unlike the situation in Germany, the possibility of counter-proof of Jewish racial descent despite membership in a Jewish community should be entertained in Holland. The final decision was up to Dr. A. Seyss-Inquart, Reich Commissioner for the Netherlands, and Dr. F. Wimmer, both seasoned lawyers. In approving the proposal of their colleague Calmeyer, they failed to realize that they had created a loophole through which numerous Jews would be able to escape the fate that was in store for them.

As soon as the decision became known in Jewish circles, petitions began to arrive at Calmeyer's department requesting that the status of a parent or grandparent be changed from Jewish to half-Jewish or even “Aryan.” Even a Mischling Grade I was exposed to far less stringent persecution.

How could a person prove that he was not a Jew according to the German racial interpretation? First, there were the baptismal certificates issued by the various churches. These were readily supplied in applicable cases, and, failing that, they could relatively easily be forged by experts familiar with the contemporary handwriting and access to paper looking more or less a century old. Such forgeries were in fact produced on a large scale. Another stratagem underlying many other petitions was to try and prove that the grandparent or parent in question had been an “illegitimate” child of a Jewish mother and an Aryan father and had subsequently been formally adopted by a Jewish husband. Such proof required an official extract from the population register, although even the testimony of one or more elderly residents who were prepared to perjure themselves by gossip mongering turned out to be sufficient. It is unnecessary to stress that the production of genuine-looking “Calmeyer-certificates” required considerable archival experience and artistic skill.

Calmeyer himself, who was rigorously correct and incorruptible, was never personally involved in any forgeries. His - equally grave - responsibility was to adjudicate requests that he personally knew to be based on insufficient or nonexistent evidence. In certain cases he demanded anthropological examinations, which were performed by Prof. Dr. Hans Weinert from Kiel, a morphologist who invariably produced favorable reports testifying to the non-Jewish physical characteristics of the applicant. His minimum fee for such examinations was Dfl. 750, but, in certain cases, he is known to have demanded many times this amount.

Ultimately, Calmeyer's decision to support a particular request would depend on whether or not a fairly superficial examination might reveal the spuriousness of the claim, thus endangering all his subsequent approvals. Obviously this was not an objective criterion, apart from the fact that, in the course of time, his judgement became more and more erratic as hostile German bodies, including the SD and the SS, increased their pressures to revoke his authority. The more fanatical and racist Nazis called Calmeyer's activities Abstammungsschwindel (genealogical fraud), and they demanded a case by case check of all his approvals. These demands became even more persistent when several so-called “Calmeyer-Jews,” among them well-known Jewish personalities, decided to reclaim the possessions they had initially surrendered to the Lippmann-Rosenthal Bank, which administered assets confiscated from Jews.

SS-General Rauter demanded that Dr. Wimmer appoint a committee in which a Dutch SS member, Ludo ten Cate, should also be a member. In the course of the years, Ten Cate had assembled a collection of 100,000 file cards containing information on Jewish subjects, including considerable information about the Dutch colony of Surinam. The latter was of particular danger for, since the war had interrupted communications with this Dutch colony, many petitions reaching Calmeyer's office were based upon alleged information from Surinam archives.

Ten Cate, a SS protègè, had been appointed, in early 1942, to the position of Official Representative for Genealogical Certificates, which was evidently a move against Calmeyer. Eventually, however, Ten Cate became involved in a vehement quarrel with other National-Socialist experts, leading to his dismissal in August 1944.

Nonetheless, the SS refused to let go. In March 1944, an order arrived from the RSHA (Reich Security Main Office)in Berlin demanding a closer examination of all Calmeyer's decisions, and, in August 1944, Zopf, the head of Referat IV B4 at the Hague, required the same. However the rivalry between Wimmer, himself a rabid antisemite, and Rauter was so intense that these demands were not acted upon. Neither, by the way, did Calmeyer implement an earlier instruction by Seyss-Inquart forbidding him to take on new cases after December 1942.

Furthermore, Calmeyer made an effort to protect mixed marriages. Nazi Germany knew the concept of “privilegierte Mischehen,”mixed Jewish-Aryan couples where either the husband was Aryan or the children had not been brought up in the Jewish faith. The Jewish partners of these marriages were – before summer 1944 - usually exempted from deportation. Calmeyer attempted to introduce the same distinction in Holland, and, at a given moment, he even succeeded in warming Seyss-Inquart to the idea. However, Rauter and other fanatical Nazis within the German occupation regime insisted that all Jewish partners of mixed marriages, whether or not they had children, should be deported. Ultimately, the “privileged mixed marriage”exemption was not introduced in the Netherlands, leaving only the non-Jewish partners and children of mixed marriages unaffected by the deportation decree.

It stands to reason that Calmeyer, who participated in numerous meetings with the top leadership of the Reichskommissariat during which the fate of the Jews was discussed, was exposed to heavy psychological pressure, in the event that he be branded a supporter of the Jews. As a result, his decisions were increasingly dictated by Fingerspitzengefühl (intuition) rather than rational thought. A typical example was related by the lawyer Benno Stokvis, who personally approached Calmeyer with a case concerning a family of six persons. Calmeyer declined the case, following which Stokvis told him that “he (Calmeyer) might have difficulty sleeping with the knowledge of being responsible for the death of six people.” Calmeyer's face turned scarlet, so much so that Stokvis was afraid he might get a heart attack. After he had recovered, Calmeyer said: “All right, I'll approve it.”

Particularly problematic proved to be a collective request on behalf of a large group of Portuguese Jews. If approved, this would have exempted no fewer than 4,304 persons. The request was endorsed by several well-known anthropologists, who acted on the assumption that all Portuguese Jews in the Netherlands were descended from Marrano forebears. Calmeyer reacted by saying that “he had only a small vessel, that would surely sink by accommodating such a large number of passengers.” Sinking, in this case, would have meant the revision of all requests, including those that had been approved earlier. Consequently, he suggested that, in the meantime, only the 386 most credible cases should be reprieved. Rauter, on the other hand, insisted that even these should be subjected to a closer examination by German experts in the Westerbork transit camp, at which point it appeared that eighty-seven of them had already gone into hiding. The German verdict was damning: “Rassisches Untermenschentum,” (racial sub-humans) they were called, and, on February 25, 1944, the group was sent to Theresienstadt.

From there nearly all of them were deported to Auschwitz to be murdered. The overall results of Calmeyer's interventions were impressive, as the following summary indicates: Out of a total number of 4767, he recognized 2026 as half-Jewish, 873 as Aryans and rejected 1868.

In analyzing these figures, it should also be taken into account that the descendants of those cleared were also exempted from further persecution as Jews. In addition, the petitioners themselves were protected against deportation while their applications were being processed, enabling them, if necessary, to go underground. It is known that some petitioners were warned by secretaries at Calmeyer's office as soon as their requests had been turned down, enabling them to disappear from their homes before the German police reached them.

The above figures show that 60 percent of all applications were approved; the majority on the basis of clearly fictitious documentation. Consequently, we can say that at least 3,000 Jewish lives were saved.

So secret and discreet were Calmeyer's machinations that even Lages, the German chief of the Amsterdam police, felt constrained to declare after the war that “to him Calmeyer's activities had always been a book with seven seals.”

On March 4 1992 Yad Vashem recognized Hans Calmeyer as Righteous Among the Nations.