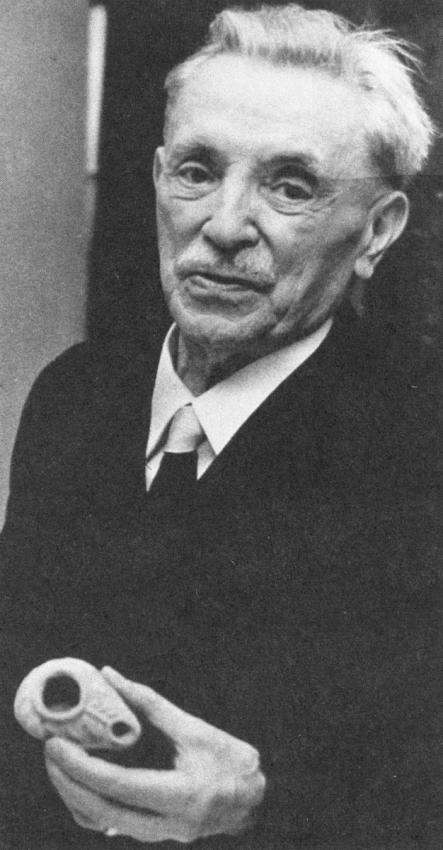

Hermann Maas was born on August 5, 1877 in Gegenbach/Schwarzwald. Through both his father’s and mother’s sides, he was descended from a family of Protestant pastors from Baden. Having studied theology at the universities of Halle, Strassburg, and Heidelberg, in the autumn of 1900, he entered the office of curate, which was the beginning of a life-long career in the Protestant church.

Since the days of the Sixth Zionist Congress in 1903, which Maas had visited out of curiosity while on a stay in Basel, he became a friend of the Jewish people and an ardent sympathizer of the Zionist movement. At the Congress he witnessed the passionate debate between the proponents of the “Uganda plan” and those faithful to “Zion” and had the opportunity of meeting with such prominent Jewish political leaders as Herzl and Weizmann, and with the German-Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, with whom he maintained a life-long connection. As an adherent of the Christian oecumenical movement, he became a staunch supporter of the cause of understanding among the monotheistic religions and, in particular, a champion of Christian-Jewish reconciliation.

On April 1, 1933, the very day that the Nazis launched the general economic boycott against the Jews of Germany, Maas set sail for the Holy Land for a three-month tour financed by a grant from the “German Palestine Committee.” The encounter with Jewish Palestine—the sight of the new Jewish settlements, meetings with freshly arrived German-Jewish emigrants, and contacts with Hebrew scholars—left an indelible impression on the Protestant theologian who himself was a fluent Hebrew-speaker.

On his return to Heidelberg at the beginning of July, Maas was exposed to a concerted campaign of vilification and threats conducted against him by the local Nazi propaganda leaders and the SA. Local Nazi party circles demanded that the “pastor of the Jews” be excluded from the pulpit. However, Maas was a too highly respected figure in the Christian world oecumenical movement, and the regime was as yet wary not to risk an international scandal.

This first serious conflict with the new rulers of Germany seemed only to intensify Maas’s defiance and the extent of his identification with the Jewish people. He contributed articles to the German Zionist paper, Jüdische Rundschau, translated poems of the Hebrew poet Chaim Nachman Bialik, and did not hesitate to send his eldest daughter to Palestine to teach young Zionists the art of hand-weaving. He would invite Jewish religious leaders in Heidelberg to join him on Christmas eve and, in turn, would participate in the Jewish Passover celebration (Seder). The connection was so strong that Heidelberg Rabbi Dr. Fritz Pinkuss had to counsel him earnestly against attending Jewish public prayers so as not to put himself in danger.

Maas was a member of the Pfarrernotbund, the emergency association for dissident Protestant pastors set up by Niemöller in September 1933, and joined the “Confessing Church”, the opposition to the pro-Nazi “German Christians” within the Protestant Church. He was also a co-founder of the “Büro Grüber” in Berlin. In October 1940, while the Jews of Baden, the Palatinate and several places in Baden-Württemberg, were being deported to a concentration camp in sothern France, Maas succeeded in protecting some of the older and the frail from being included in the deportation. He kept in contact with those who were deported, using his connections to help them obtain exit visas abroad.

In March 1942, the Reich Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs started a campaign against Maas that ended in his forced retirement in mid-1943. One of the most incriminating pieces of evidence against him was the discovery of a bundle of letters in which the dissident clergyman expressed his abhorrence of the National-Socialist regime and its racial persecution of the Jews. The vindictiveness of the regime was not satisfied, however, and, in 1944, the sixty-seven-year-old was sent to a forced-labor camp in France. Only the entry of the Americans brought about his release and ended his tribulations.

In 1950, Hermann Maas became the first German to be officially invited to visit the State of Israel. He wrote several books about Israel, Judaism, and Christianity. He died in Heidelberg in 1970.

On July 28, 1964, Yad Vashem decided to recognize Reverend Hermann Maas as Righteous Among the Nations.