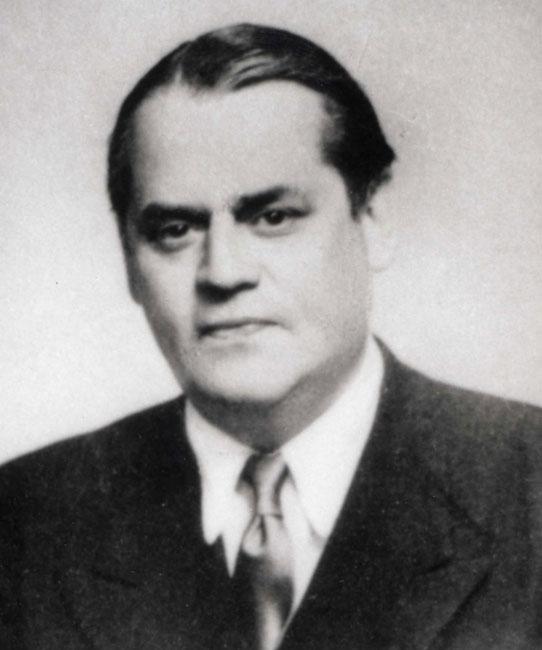

Baron Friedrich Carl von Oppenheim was born on October 5, 1900 in Cologne. He was a distant descendant of the German-Jewish banker Salomon Oppenheim, Jr, (1772-1828), who, at the end of the eighteenth century, had established in Cologne the famous banking house of Sal Oppenheim Jr. & Cie. The bank had played an important role in the industrialization of the Rhein-Ruhr region, especially through its involvement in financing the construction of railway and waterway communications and the development of the coal and steel industries.

Salomon Oppenheim Jr.’s two sons, Simon and Abraham, were ennobled in 1867 and in 1868 respectively. Simon’s sons, Albert and Eduard, converted in 1858 and in 1859 respectively, and married non-Jewish spouses. Baron Friedrich C. von Oppenheim and his brother Waldemar, Salomon Oppenheim, Jr’s great grandsons, were considered by the Nazis as “quarter Jews,” or “Mischlinge (cross-breeds) of the second degree.” Although they were excluded from the Nazi party and, consequently, from holding positions of power, “quarter-Jews” were allowed to retain their German citizenship, serve in the military, and intermarry with Germans.

In the period immediately following the Nazi takeover in 1933, the Oppenheim banking firm in Cologne and its employees were subjected to a certain degree of harassment from Nazi party circles. Baron Schröder, head of the private banking group within the Nazi party and “Gauwirtschaftsberater” (a title for a local Nazi economic chief), was especially involved in these activities. However, barring the fact that, in 1938, it was forced to change its name to “Pferdmenge (after Dr. Robert Pferdmenge, a non-family partner who lent his name) & Co,” the bank was by and large allowed to carry on its normal business.

Although Friedrich von Oppenheim, who had never hidden his dislike of Nazism, was subjected to special Gestapo surveillance after 1938, he continued to enjoy some protection by virtue of the economic importance of his indispensable business connections abroad. Both Friedrich von Oppenheim and his elder brother, Waldemar, were inducted, after the outbreak of war, into Canaris’ Abwehr (German counter-intelligence), which entitled them to a special pass and virtually unrestricted travel abroad.

Baron Friedrich von Oppenheim himself continued to maintain close business contacts and friendly relations with Jews after the Nazi takeover, in disregard of Nazi propaganda and his own heightened vulnerability as a so-called Mischling. Sensing, in 1938, that the danger to Jews was imminent, he urged the Griessman and Lissauer families, with whom he had close business contacts, to leave Germany. He helped them emigrate and to set up their business, which dealt in metal manufacture, in the Hague and in Amsterdam. He continued to maintain contact with them even after their emigration.

In May 1940, the German invasion of the Netherlands again caught up with von Oppenheim’s Jewish friends, but he was not prepared to leave them in the lurch. In September 1940, he finally succeeded in obtaining exit visas for them from Holland to Portugal and from there to South America. He traveled in person to the Netherlands to part from his friends and arrange the details of their escape plan. On September 7, 1940, a special German bus, commanded by German Abwehr officers, arrived at the Lissauers’ residence at 4 Minerva Plein, Amsterdam, and took them, together with the Griessman family—eleven persons in all—through occupied Belgium and France to the safety of the Spanish border at Irun. From Spain they took the train to Portugal and from there traveled by ship to Brazil.

After the Germans began deporting the Dutch Jews in 1942, von Oppenheim was active in a largely unsuccessful attempt to save the lives of the Jewish workers of the Oxid firm in Amsterdam. The firm, which had previously belonged to the aforementioned Lissauer and Griessman families, was taken over in 1940/41 by the Oppenheim bank—alias Pferdmenge & Co.—together with another German company. Since the Oxid firm was engaged in the production of certain metal alloys that were of importance to the German ammunitions’ industry, its Jewish workers—most of them former German-Jewish refugees—enjoyed a relatively protected status. This fact was used by von Oppenheim—who also lobbied other bodies with whom he stood in contact, like the Reichsbank and the Ministry for Military Production—in his appeal against their deportation. However, these efforts largely came to naught, with the intensification of the anti-Jewish campaign in the Netherlands. In 1943, von Oppenheim personally went to Aus der Funten, the SS Chief in the Netherlands, to plead for the exemption of Dr. Hugo Weil, the former Jewish director of Oxid who had been incarcerated in Westerbork pending his deportation. This was of no avail: Weil was included in a transport from Westerbork to Bergen-Belsen and perished there. In the end, only ten Jewish Oxid workers (out of an estimated eighty) survived the Holocaust.

There is also considerable evidence regarding von Oppenheim’s efforts on behalf of other Jewish individuals who were either in hiding or under arrest. Thus, in November 1941, he dispatched an employee, the Swiss-national Ernst Gut, to Switzerland for the sole purpose of phoning friends in New York to raise money for immigration permits for certain Jewish persons. Von Oppenheim also extended help to Cologne Police Chief Karl Winkler, who was of Jewish descent, from the time that Winkler and his family went into hiding at the beginning of 1944, until his own arrest in September.

Following the abortive attempt on Hitler’s life in July 1944, von Oppenheim, who had long been targeted by the Gestapo, was arrested and thrown into prison pending his trial on charges of treason. In an attempt to frame him, the Gestapo produced, in August 1944, fabricated evidence to prove that his mother was of Jewish descent and hence that he should be treated as a “half-Jew,” or “Mischling of the first degree.” This by itself could have had fatal consequences for the outcome of his trial. Fortunately, however, the interrogation dragged on until the end of the war, and von Oppenheim was able to survive in prison until he was released by the Americans.

After the war the Oppenheim firm, which reverted in 1947 to its original name, resumed its banking activity, becoming one of the largest private banking concerns in the Federal Republic of Germany.

On October 10, 1996, Yad Vashem decided to recognize Baron Friedrich von Oppenheim as Righteous Among the Nations.