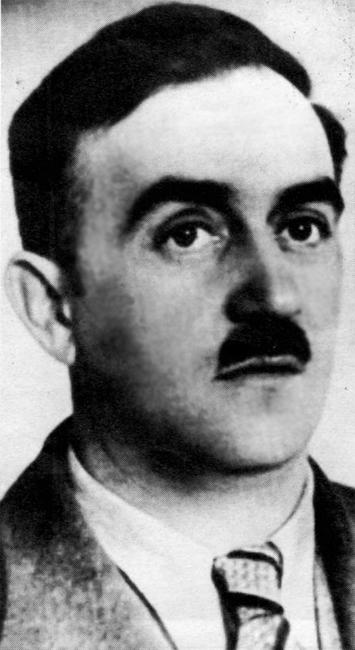

The Soldier "Whose Heart was in Jewish Matters"

Anton Schmid was born in Vienna in 1900. He owned a radio shop was married with one daughter. When the Second World War broke out he was drafted into the German army (in 1938 Austria became part of Germany and therefore all Austrians were now German citizens). He served first in Poland, and after the attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 in the newly occupied territories. Schmid was stationed in Vilna, and put in charge of the Versprengten-Sammelstelle – the army unit responsible for reassigning soldiers who had been separated from their units. His headquarters were situated in the Vilna railway station, and like all the people in the area, he became witness to the persecution and murder of the Jews. Soon rumors spread in the ghetto that an Austrian soldier was being friendly towards Jews. It was Schmid who used every possibility to help the Jews. He employed them as workers for his military unit, provided papers to some, got others released from the infamous Lukiski prison, used his army trucks to transfer them to less dangerous places, and went as far as to shelter Jews in his apartment and office.

Herman Adler and his wife Anita were members of the Zionist movement in Vilna. When Adler was in danger, Schmid arranged a hiding place for the couple at his home. At Adler's request Schmid met with one of the leaders of the Dror pioneer movement, Mordechai Tenenbaum-Tamarof. A special relationship was forged between the Wehrmacht soldier and the Jewish Zionist activist. Schmid began to help the Jewish underground.

Schmid repeatedly used military vehicles to smuggle Jews from Vilna, where danger seemed to be greater at that time, to other places where there was relative quiet; he took members of the resistance movement from Vilna to Bialystok and even to Warsaw; he facilitated contact between the Jewish underground groups in various locations, passing messages and transferring activists. In October 1941 in an attempt to reduce the Jewish population of Vilna, the Germans distributed 3,000 yellow colored permits to expert workers. Each permit protected its owner and three members of his family, and all the remaining Jews – those without permits – were to be killed. Schmid made sure that his Jewish workers got as many permits as possible, and helped smuggle the others out of Vilna.

On 31 December 1941 Schmid hosted the leadership of the Dror Jewish underground in his apartment to mark the New Year. He used the occasion to once again express his repulsion towards Nazism. Tenenbaum, also present, responded that when the Jewish State would come into being after the war, it would honor Schmid for his help to the Jews. Schmid replied that he would wear that award with pride. Regrettably, both men did not live to see the end of the war, the establishment of the State of Israel and the Jewish State’s recognition of Schmid’s heroism.

As time went on, Schmid's exploits got bolder. He was warned by Tenembaum that knowledge about his help to the Jews had widely spread and that he was in grave danger. But Schmid persisted and went on helping the persecuted Jews. He was to pay for his humanity with his life. In the second half of January 1942 he was arrested and court-martialed for high treason. After being found guilty, he was executed in April 1942.

Before his execution he wrote a letter to his wife from his prison cell – "I only acted as a human being and desired doing harm to no one."

It was not only Schmid who suffered the consequences of his humane and brave conduct. After her husband's execution, Schmid’s widow and daughter suffered abuse from their neighbors for his alleged treachery. In those days there was wide popular support of Nazism. It is only many years after the war that a street in Vienna was named after Schmid.

In 1964 – over twenty years after Schmid’s execution and Tenebaum’s death in the Bialystok ghetto uprising – Tenenbaum’s promise to Schmid was fulfilled. Yad Vashem bestowed the title of Righteous Among the Nations on Anton Schmid.