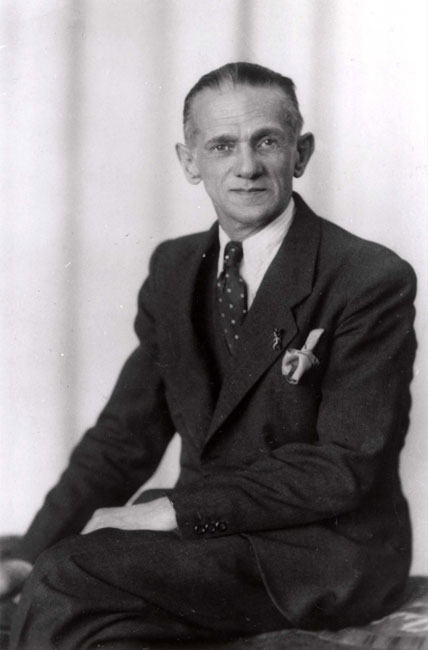

Otto Weidt (b. 1883), of working-class origins, was compelled by his growing blindness to abandon his work as a wallpaper hanger. He thereupon set up a workshop for the blind in Berlin Mitte, which manufactured brushes and brooms. Practically all of his employees were blind, deaf, and mute Jews. They were assigned to him from the Jewish Home for the Blind in Berlin-Stegliz. When the deportations began, Weidt, utterly fearless, fought with Gestapo officials over the fate of every single Jewish worker. As means of persuasion he would use both bribery and the argument that his employees were essential for fulfilling orders commissioned by the army. Once, when the Gestapo had arrested several of his workers, the self-appointed guardian of the Jewish blind went in person to the assembly camp at the Grosse Hamburger Strasse, where the Jews were incarcerated pending deportation, and succeeded in securing their release at the last minute. Aside from the blind, Weidt also employed healthy Jewish workers in his office. This was strictly forbidden, as all Jewish workers had to be mediated through the labor employment office, which would ordinarily post them to forced-labor assignments. However, Weidt, through a mixture of bribery and subterfuge, succeeded in overriding the objections of the Nazi director of the official employment office. The Jewish Inge Deutschkron was among the eight healthy Jews employed at the workshop. As she and her mother began to live illegally in order to escape deportation, Weidt arranged an Aryan work permit for Deutschkron that he had acquired from a prostitute, who had no use for it. Unfortunately, the ticket had to be discarded three months later when the police arrested the prostitute. One of Weidt’s most spectacular exploits involved the rescue of a Jewish girl who had been deported to the camps in Poland. Alice Licht and her parents were accommodated at a “secondary site” of the workshop, ensconced behind a front of brushes and brooms. When the Gestapo, tipped off by a Jewish informer, discovered the hiding place, Licht was deported first to Theresienstadt and from there to Auschwitz and to Christianstadt (a sub-camp of Gross Rosen). According to her testimony, Otto Weidt traveled to the camp to search for her. Licht told Yad Vashem that Weidt made plans for her escape, but they did not materialize. When the inmates of Christianstadt were taken on a death march, Licht managed to make her escape and return to Berlin. By that time Weidt's apartment had been destroyed by a bombing, but he sheltered her until the end of the war. Alice Licht's parents never returned.

On September 7, 1971, Yad Vashem recognized Otto Weidt as Righteous Among the Nations.