Sunday to Thursday: 09:00-17:00

Fridays and Holiday eves: 09:00-14:00

Yad Vashem is closed on Saturdays and all Jewish Holidays.

Entrance to the Holocaust History Museum is not permitted for children under the age of 10. Babies in strollers or carriers will not be permitted to enter.

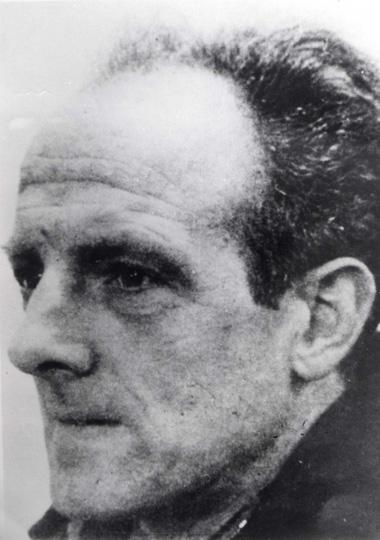

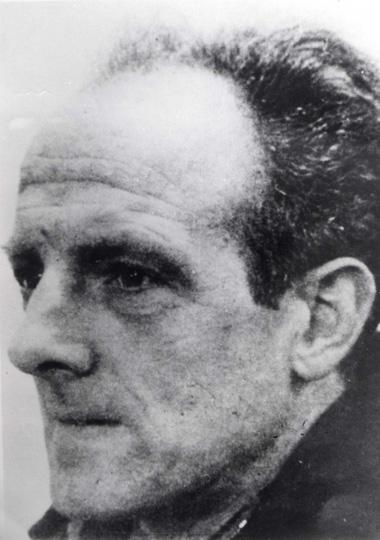

Johan (Joop) Westerweel was one of the most daring and successful of the Dutch Resistance leaders until his execution by the Nazis in August 1944. His background in education and his unconventional parents, who belonged to a non-consensual sect of Protestantism - the Derbists – may have prepared him for the unique rescue operation that he set into motion.

Joop’s motto was one of non-violent resistance. As a convinced pacifist, he had been expelled from the Dutch East Indies for refusing to be drafted into the army. Joop never abandoned his idealistic principles. His strict Christian background instilled in him a sense of justice for all and a belief in the basic goodness of man. He began teaching in a school at the Werkplaats in Bilthoven, where the progressive and innovative educational methods of its founder, Kees Boeke, were applied.

In 1940, Joop and his wife, Wilhelmina (Wil), moved to Rotterdam, where Joop was offered a position as principal of one of the Montessori schools. In Bilthoven, the Westerweels had already come into contact with Jewish refugee children, who had been arriving in Holland in the 1930s, mainly from Germany.

By 1942, the couple had four children. Nevertheless they dedicated their lives to helping others, and had been taking Jewish refugees into their home. Joop’s colleague and friend from the Werkplaats, Mirjam Waterman (later Pinkhof), introduced him to a group of young Zionist pioneers (halutzim) in Loosdrecht, near Amsterdam. Joop recognized a sense of idealism and strong principles in this group and felt a great affinity to them. The community consisted mainly of youngsters, aged between 15 and 19, originating from Central and Eastern Europe. They had come to Holland for agricultural training in preparation for immigration to Eretz Yisrael. Joop admired the group’s cohesiveness, their inner discipline, and their optimism. Most of all, Joop admired Shushu (Joachim) Simon, a young intellectual from Berlin in whom he discovered a soul mate, a fellow thinker-idealist, with whom he formed a close friendship.

When the Loosdrecht group received a tip-off from the Jewish Council on August 15, 1943, that they were about to be deported, Joop and his friends, who became known as the Westerweel group, were on hand to provide a hiding place for each of the 50 members. By August 17, 1943, all the young pioneers had found shelter, and 33 out of this group of 50 survived the war, the rest were deported after betrayal.

Joop and his colleagues realized that hiding was far from being a perfect solution. They had heard of the possibility of crossing the border into Belgium and from there traveling to France and neutral Spain, where it would be possible to reach Eretz Yisrael by boat. The Westerweel group, in collaboration with the Hehalutz movement, decided to concentrate on helping the members escape Dutch territory altogether. In September 1942, an attempt was made to help eight Jewish pioneers escape to neutral Switzerland. The group was caught crossing the Dutch-Belgian border and all were arrested and deported to Auschwitz. A second group reached Switzerland. In December 1943, Joop succeeded in leading a group of halutzim from Holland through Belgium to France. From there they could cross the border to Spain and ultimately reach Eretz Yisrael. At the foot of the Pyrenees, in a dramatic address to the young halutzim with whom he was about to part, Joop urged them to remember the suffering in the world at large. He implored them to accord freedom and dignity to all inhabitants of a future Jewish State. “No more war,” were his final words as they parted company.

Later that month, Wil was arrested during an attempt to free Lettie Rudelsheim (later Ben Heled), one of the most active halutz members, from the Scheveningen prison. Wil was taken to the Vught concentration camp, where she remained for about a year, and during which time she witnessed the execution of her husband. She was later transferred to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she was subjected to forced labor and contracted a heart disease. She was eventually allowed to go to Sweden as part of a prisoner exchange and returned to Holland after the war.

Following his wife’s arrest, Joop put his four children went into hiding with friends of the family. He quit his post at the Montessori school and went underground. On March 11, 1944, Joop and his co-worker Bouke Koning were caught at the Belgian border with two Jewish women from Youth Aliyah whom they were escorting. Joop was imprisoned in Vught and tortured. He soon became a spiritual leader for many of the prisoners since his unfailing high spirits in the face of cruel interrogation and the prospect of execution gave those around him hope and strength. His last communication with the outside world was a poem, entitled “Avond in de Cel” ( Evening in the Cell), written in July 1944, and full of optimism, speaking of the beauty of nature and a life of fulfillment and inner conviction. On August 11, 1944, Joop Westerweel was executed in the Vught concentration camp.

One of the Westerweel children, Marta, settled in Israel, where she met many of her father’s survivors. “I was three-and-a-half years old when my father was arrested and five years old when he was executed. I never really knew him. In the Netherlands I was a fatherless child; here in Israel I became my father’s daughter”, she says. It was from the survivors that she heard stories about her father. “I know the survivors endured terrible tragedies”, she says, “but in a way I envy them, because they had known my father”.

On June 16, 1964, Yad Vashem recognized Johan Gerard Westerweel and his wife, Wilhelmina Dora Westerweel-Bosdriesz, as Righteous Among the Nations.

Thank you for registering to receive information from Yad Vashem.

You will receive periodic updates regarding recent events, publications and new initiatives.

"The work of Yad Vashem is critical and necessary to remind the world of the consequences of hate"

Paul Daly

#GivingTuesday

Donate to Educate Against Hate

Worldwide antisemitism is on the rise.

At Yad Vashem, we strive to make the world a better place by combating antisemitism through teacher training, international lectures and workshops and online courses.

We need you to partner with us in this vital mission to #EducateAgainstHate

The good news:

The Yad Vashem website had recently undergone a major upgrade!

The less good news:

The page you are looking for has apparently been moved.

We are therefore redirecting you to what we hope will be a useful landing page.

For any questions/clarifications/problems, please contact: webmaster@yadvashem.org.il

Press the X button to continue