Introduction

After the war, the western Allies established DP camps in the Allied-occupied zones of Germany, Austria and Italy.

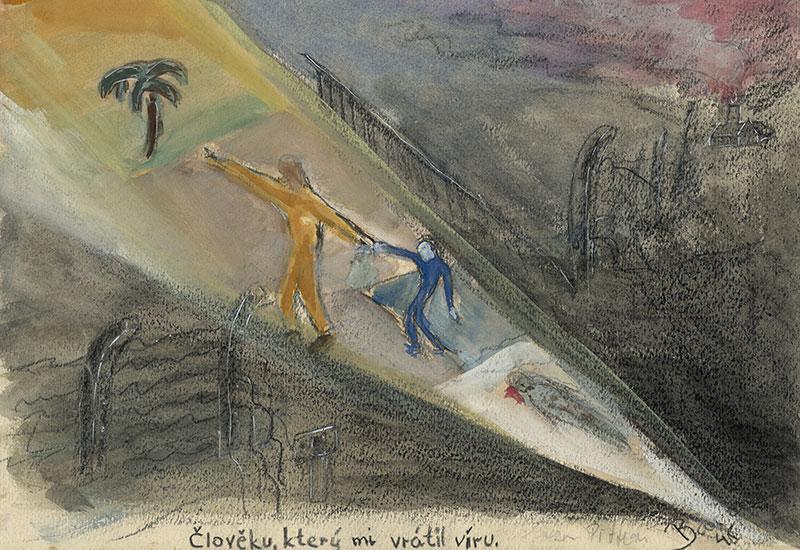

The first inhabitants of these camps were concentration camp survivors who had been liberated by the Allies on German soil. Conditions in these camps, especially at the beginning, were very difficult. Many of the camps were former concentration camps and German army camps. Survivors found themselves still living behind barbed wire, still subsisting on inadequate amounts of food and still suffering from shortages of clothing, medicine and supplies.

“Everything is seen in too sharp a light and is heard too loudly. Everything is beyond the human scale; and if you have breathed that air, you will understand that here live people who have already experienced their deaths long ago. Camp eyes are still saturated with the visions of suffering, camp lips smile a cynical smile, and the survivors' voices cry, 'We have not yet perished'."

(Testimony of Haim Avni, emissary from Eretz Israel)

In the DP camps, Holocaust survivors sometimes lived alongside antisemites and individuals who had harmed Jews during the war. In the summer of 1945, Earl Harrison, US President Truman’s emissary to the camps, wrote a report on the Jews’ suffering in the DP camps. As a result, the Jewish refugees were transferred to separate camps where they were given a degree of independence, and conditions improved. The Americans enabled US Jewish relief organizations and activists from Eretz Israel to operate in the camps. The living conditions in the British-occupied zone, where Jewish refugees had arrived mostly from Bergen-Belsen, were far less comfortable.

Survivor Eliezer Adler recalls:

They would take a hut and divide it into ten tiny rooms for ten couples. The desire for life overcame everything - in spite of everything I am alive, and even living with intensity.

We took children and turned them into human beings…. The great reckoning with the Holocaust? Who bothered about that... you knew the reality, you knew you had no family, that you were alone, that you had to do something. You were busy doing things. I remember that I used to tell the young people: Forgetfulness is a great thing. A person can forget, because if they couldn't forget they couldn't build a new life. After such a destruction to build a new life, to get married, to bring children into the world? In forgetfulness lay the ability to create a new life...

After the Holocaust, there were tens of thousands of Jewish survivors in Poland, as well as refugees who had returned there from the Soviet Union. On comprehending the enormity of the destruction of Polish Jewry and being confronted with manifestations of antisemitism, which reached their zenith with the Kielce pogrom of July 1946, these Jews decided to move westward to the American-occupied zone, and so they too arrived at the DP camps. In 1947, they were joined by a further wave of Jewish refugees from Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania, and the total number of DP camp inhabitants reached a peak of some 250,000.

Life in the camps in occupied Germany was regarded by most of the Jewish refugees as a temporary arrangement. They sought to leave Germany, and in many cases, Europe as a whole. Yet despite this, and despite the wretched physical conditions, the survivors in the DP camps transformed them into centers of social, cultural and educational activity.

Holocaust survivor and author Aharon Appelfeld relates:

The first entertainment troupes made their appearance: a mixture of old and young people, among them former actors… and all manner of skinny people who found this distraction cathartic. These troupes evolved spontaneously, and went from one camp to another. They sang, recited, told jokes… the subconscious will to exist propelled us back into the circle of life.

The Jews in the DP camps established theaters and orchestras. They held sporting events and published more than 70 newspapers in Yiddish. They were among the first to research the Holocaust and initiate commemoration events. They collected testimonies from survivors, gathered written documentation and held memorial ceremonies for the victims.

The survivors found themselves “liberated but not free”. Their starting point was their unique legacy, but their response was a national one. “In the DP camps, without the framework of a society to absorb them, their rehabilitation was dependent on the formation of a new society, one which struggled for its national existence while fighting for the rehabilitation of its members. The camps were a model for the incremental move from a bruised and battered Europe to a new life - in Israel and America,” wrote researcher Hagit Lavsky.

Different Jewish political parties – secular and religious, Zionist and Socialist – operated in the DP camps, the legacy of the intensive political life led by the Jews of Poland before the Holocaust. With that, the trauma engendered by the Holocaust and the influence of the Zionist activists who came from Eretz Israel meant that the political inclination in the DP camps was predominantly Zionist.

There was a high level of political awareness in the DP camps, and a desire to leave Germany, especially to Eretz Israel. The Jews established Kibbutzei Hachsharah (pioneer training collectives) in which they prepared themselves for Aliyah (immigration) to Eretz Israel.

Due to the establishment in 1948 of the State of Israel and the changes that were made to the US immigration legislation, there were increased opportunities for many of the Jews in the DP camps to emigrate. All the DP camps closed by 1950, except for Föhrenwald, which remained operative until 1957. Most of the displaced persons immigrated to Israel, approximately one third to the US, and several thousand settled in Europe, including in Germany itself, and reestablished communities that had been destroyed in the Holocaust.

Related Video