Architecture of Murder

The Auschwitz-Birkenau Blueprints

“There is a place on earth that is a vast desolate wilderness, a place populated by shadows of the dead in their multitudes, a place where the living are dead, where only death, hate and pain exist.”

Giuliana Tedeschi

The Auschwitz camp complex has become a universal symbol of the Holocaust. Research scholars at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum estimate that approximately 1.1 million people were murdered in Auschwitz, of whom a million were Jews. The Auschwitz complex was not built overnight. This was a major construction project that lasted years and was never completed. A number of organizations and companies were involved in the building process, as well as thousands of workers, both German and foreign. What started as a single camp with 22 buildings in 1940 became a complex of 3 main camps and 40 sub-camps.

The Auschwitz camp complex has become a universal symbol of the Holocaust. Research scholars at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum estimate that approximately 1.1 million people were murdered in Auschwitz, of whom a million were Jews. The Auschwitz complex was not built overnight. This was a major construction project that lasted years and was never completed. A number of organizations and companies were involved in the building process, as well as thousands of workers, both German and foreign. What started as a single camp with 22 buildings in 1940 became a complex of 3 main camps and 40 sub-camps.

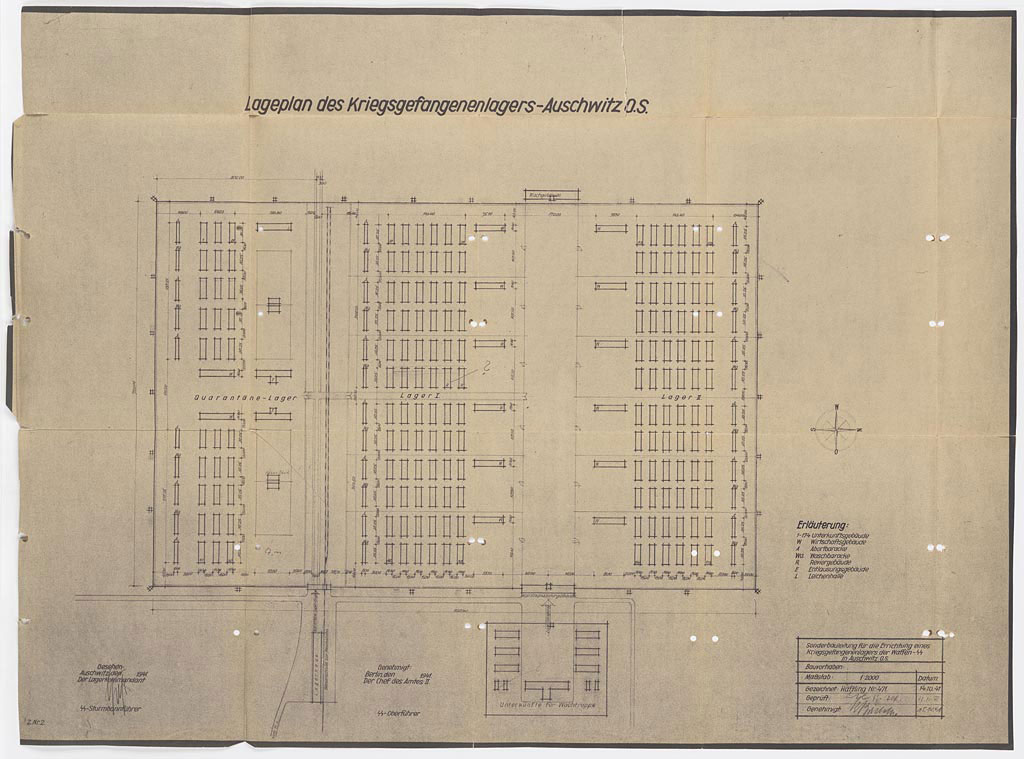

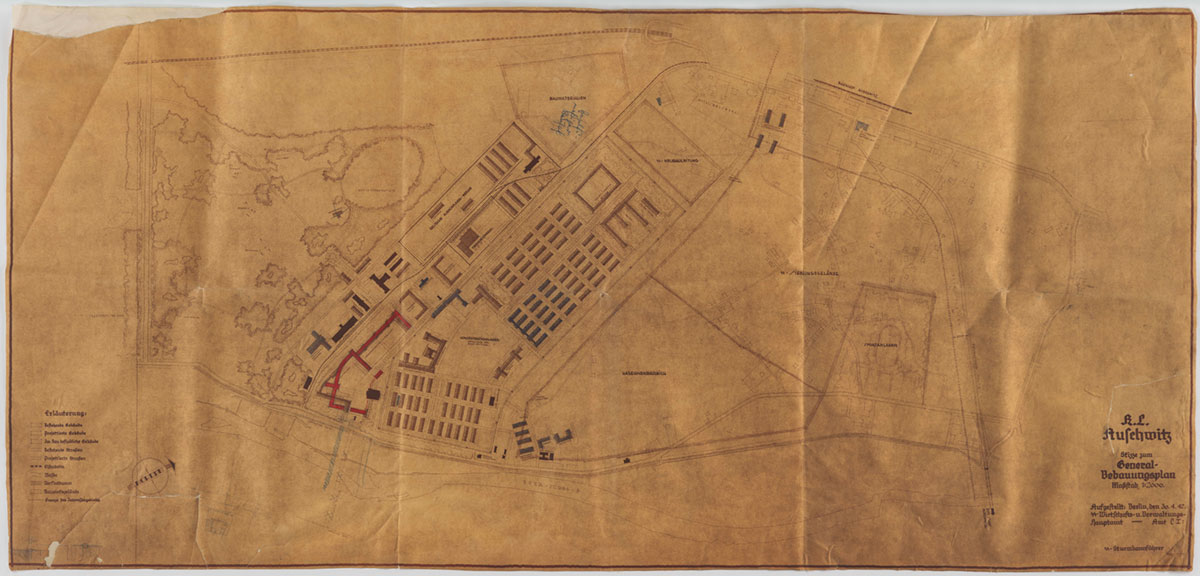

In the course of the planning phase, hundreds of technical drawings of the different construction sites and the buildings to be erected on them were produced by the different offices and companies involved in the project. The plans were drawn up by SS draftsmen, prisoners with a technical background who were employed by the planning offices, and civilian draftsmen. These plans were used by the contractors to present the project, and to carry out the construction work. The plans included detailed drawings of the gas chambers and the crematoria.

The Germans established the first camp at Auschwitz in the spring of 1940, on a site previously serving as a barracks for the Austro-Hungarian artillery in Upper Silesia. This was the first concentration camp to be set up in Poland, and the first prisoners were brought there in June of the same year.

The Germans established the first camp at Auschwitz in the spring of 1940, on a site previously serving as a barracks for the Austro-Hungarian artillery in Upper Silesia. This was the first concentration camp to be set up in Poland, and the first prisoners were brought there in June of the same year.

In the course of 1941, there were two developments that contributed to the dramatic increase in the scope of German activity at Auschwitz.

In early 1941, the Petro-Chemical Corporation I.G. Farben decided to establish a huge factory there for the production of synthetic rubber and fuel. The SS agreed to supply the corporation with cheap labor to build the factory and later to man it. As the construction of the factory progressed, a small labor camp was set up next to it, which was later called “Auschwitz III”.

The second development occurred with the German invasion of the Soviet Union. The Germans decided to establish a vast prisoner-of-war camp in Upper Silesia, for the many Soviet soldiers who had been taken captive. Built adjacent to the main camp, near the small agricultural community of Brzezinka, this camp was called “Auschwitz II”, better known as Birkenau.

The second development occurred with the German invasion of the Soviet Union. The Germans decided to establish a vast prisoner-of-war camp in Upper Silesia, for the many Soviet soldiers who had been taken captive. Built adjacent to the main camp, near the small agricultural community of Brzezinka, this camp was called “Auschwitz II”, better known as Birkenau.

The construction of Birkenau began in October 1941. The building was supervised by the “Central Building Authority of the Waffen SS and Police, Auschwitz, Upper Silesia”, established on 1 October, 1941, and headed by Sturmbannführer (Major) Karl Bischoff. The Blueprint Office, headed by Hauptscharführer (First Sergeant-Major) Wichmann, was responsible for preparing the construction plans, which were drawn up by SS officers who had studied architecture or engineering, and several prisoners with the appropriate technical training. Herta Soswinski, a prisoner who worked as a clerk at the Building Authority, recalls:

“The task of the Bauleitung [Building Authority] was the overall planning of all the construction works within Auschwitz, including living quarters, medical facilities, crematoria, gas chambers…The Bauleitung was not only responsible for the planning, but also for the labor itself, the allocation of materials and supervision. The SS men who worked on the plans, were also active at the building sites, when necessary.”

The camp was built on swampy, exposed terrain. The construction was carried out in stages, with the ultimate goal of accommodating some 200,000 prisoners. In the early stages, most of the labor involved in preparing the area and the construction itself was carried out by thousands of Soviet prisoners of war who worked under German supervision. As time went on, they were joined by many Polish and Jewish prisoners. The labor conditions were appalling, and the death rate of the prisoners was especially high in the winter months. Polish prisoner Alfred Czeslaw Przybylski recalls:

“In the course of digging and building the foundations, the prisoners worked in the fall, in winter and frost, standing waist-deep in water. Female prisoners at the women’s prison in Birkenau worked under the same conditions. I firmly believe that the choice of building site – on wet ground, even though they could have built on ground that was dry and more suitable for construction – a choice made by professionals…was designed to exterminate the prisoners who worked on the construction and those who inhabited the buildings.”

Unlike the brick buildings in the main camp, a considerable number of the buildings in Birkenau were uniform wooden huts that were unfit for human habitation. They did not have an efficient drainage system, or insulation against the bitter cold. They were originally intended to house some 550 prisoners each, but in practice, many more prisoners were crammed inside. The severe overcrowding in the huts caused unspeakable sanitary conditions, and led to a high death rate amongst the prisoners living in them. A former prisoner recalls the conditions inside the huts at Birkenau:

Unlike the brick buildings in the main camp, a considerable number of the buildings in Birkenau were uniform wooden huts that were unfit for human habitation. They did not have an efficient drainage system, or insulation against the bitter cold. They were originally intended to house some 550 prisoners each, but in practice, many more prisoners were crammed inside. The severe overcrowding in the huts caused unspeakable sanitary conditions, and led to a high death rate amongst the prisoners living in them. A former prisoner recalls the conditions inside the huts at Birkenau:

On rainy days, the packed-earth floor of the huts turned into a swamp as a result of the lack of drainage.

These huts were originally intended to house 500 people. Building manager Dejaco’s order to build a third lower layer of bunks increased the huts’ capacity to 800-1000, and often, not 4 but 10-12 prisoners would lie on each bunk…

Living conditions were especially harsh in winter, and as a result, many prisoners fell ill and died. Renowned author Roman Frister writes the following about the conditions in the winter months:

“The seasons changed in accordance with nature’s logic, reminding us all of the existence of laws that never change: summer ended, fall followed suit, and winter burst into our lives, lashing at us with its whip of frost. Unlike the factory, which was pleasantly warm, the huts in the camp had never been heated; the heaters inside them were used as tables. After the evening roll-call, which lasted forever, or more accurately, until the Germans got fed up, there was nowhere we could warm up. We went to sleep without undressing, sometimes without taking off our shoes. The nights brought suffering, but for me, the waking moments were the worst. They forced me to make a choice. Each morning at 5, when the Blockaelteste’s whistle woke us up, I had to decide, yet again, if I was going to fight, or give up.”

As well as the camps themselves, the SS built a considerable amount of infrastructure adjacent to the camps and between them. A complex this size needed a central heating system, a system for handling sewage and water supply, roads, different camps and buildings for the German staff, and a system for supplying food and other commodities.

Shortly after construction had begun at Birkenau, the decision was made to change its designation, and turn it into an extermination camp. The first experiments with gas were carried out in the main camp in the fall of 1941, and in the light of their success, the SS decided to build four permanent installations in Birkenau, for the specific purpose of gassing people to death. The construction began in 1942, directed by the Topf and Sons company, supervised by the SS. As a stopgap measure until the installations were completed, the Germans converted existing buildings to erect two makeshift gas chambers next to the camp.

Shortly after construction had begun at Birkenau, the decision was made to change its designation, and turn it into an extermination camp. The first experiments with gas were carried out in the main camp in the fall of 1941, and in the light of their success, the SS decided to build four permanent installations in Birkenau, for the specific purpose of gassing people to death. The construction began in 1942, directed by the Topf and Sons company, supervised by the SS. As a stopgap measure until the installations were completed, the Germans converted existing buildings to erect two makeshift gas chambers next to the camp.

The four extermination installations started operating in 1943. They each included an undressing room and a gas chamber, both underground, and a crematorium for incinerating the bodies of the murdered. These facilities made the murder of the Jews a far more efficient process.

SS man Perry Broad describes one instance of murder by gas that he witnessed:

“A number of victims noticed that the covers had been removed from the six holes in the ceiling (of the gas chamber). They screamed in terror when a head, covered in a gas-mask, appeared at one of the holes. The “disinfectors” went to work…. Using a hammer and chisel, they opened some innocuous-looking tins which bore the inscription "Zyklon, to be used against vermin. Attention, poison! To be opened by trained personnel only." As soon as the tins were opened, their contents were thrown through the holes, and the covers were replaced immediately… about two minutes later, the screams died down, and only muffled groans could be heard. Most of the victims had already lost consciousness. Two more minutes passed, and Grabner (one of the SS men) stopped looking at his watch. Absolute silence prevailed.”

The extermination reached its peak in the spring and summer of 1944, with the deportation of some 430,000 Hungarian Jews to the camp, and the subsequent murder of the majority of the deportees.

During this period, the pressure on the extermination machinery was so great that the Germans also reactivated the makeshift gas chambers that had been operating in 1942.

In tandem with its transformation into a killing center, the economic significance of the Auschwitz camp complex also grew. The massive I. G. Farben factory was never completed, but thousands of prisoners were involved in its construction over the years. In addition, other factories were set up at Auschwitz for different products. Additional factories and workshops were built near the camps and prisoners were sent to work in them. Auschwitz also served as the center for collection and distribution of forced laborers to all areas of German industry. The largest allocation of Auschwitz prisoners was made in the spring of 1944, when some 100,000 prisoners from the Auschwitz complex were transferred to the German aircraft industry.

Concrete information about Auschwitz including relatively accurate drawings of its main camps and the extermination facilities only reached the West in the summer of 1944, in the form of the Vrba-Wetzler report.

Concrete information about Auschwitz including relatively accurate drawings of its main camps and the extermination facilities only reached the West in the summer of 1944, in the form of the Vrba-Wetzler report.

Rudolph Vrba and Alfred Wetzler were Slovak Jewish prisoners who escaped from Auschwitz in April 1944. They prepared a comprehensive report on what was happening at Auschwitz, and sent it to the West via underground channels. The drawings included in the report are surprisingly accurate.

The construction work at the Auschwitz complex continued until November 1944. At this point, Himmler gave the order to halt the extermination of the Jews there, and the Germans began to dismantle the extermination facilities in order to conceal all traces of their crime. Later, the Germans dismantled further sections of Birkenau, but when the Red Army arrived on January 27th, 1945, most of the Birkenau camp was still intact.

The Germans incinerated the camp archives shortly before the Soviets arrived, but missed the construction archive, which was kept in a different building. As a result, the Soviets found a considerable amount of the technical paperwork – including many of the construction blueprints. These documents became accessible to researchers and the general public after the Cold War ended. From no other extermination camp did so much paperwork survive, including detailed documents about the extermination facilities. The Auschwitz construction blueprints thus constitute extraordinary documentation of the manner in which a major building operation served as a central tool of Nazi extermination policy. They will be preserved for perpetuity in the Yad Vashem Archives.

The Germans incinerated the camp archives shortly before the Soviets arrived, but missed the construction archive, which was kept in a different building. As a result, the Soviets found a considerable amount of the technical paperwork – including many of the construction blueprints. These documents became accessible to researchers and the general public after the Cold War ended. From no other extermination camp did so much paperwork survive, including detailed documents about the extermination facilities. The Auschwitz construction blueprints thus constitute extraordinary documentation of the manner in which a major building operation served as a central tool of Nazi extermination policy. They will be preserved for perpetuity in the Yad Vashem Archives.

Recommended reading:

- Allen, Michael Thad, The Business of Genocide. The SS, Slave Labor, and the Concentration Camps, London, 2002.

- Dlugoborski, Waclaw, Piper, Franciszek, Czech, Danuta, Auschwitz 1940-1945, vols. I-V, Oswiecim, 2000.

- Gutman, Israel & Berenbaum, Michael (ed.), Anatomy of the Auschwitz death camp, Bloomington, 1994.

- Van Pelt, Robert Jan & Dwork, Deborah, Auschwitz, 1270 to the Present, New Heaven, 1996.