When they move around this space and begin to look at the displays, the future visitors will suddenly encounter a doll, or rather the scarred head of an old doll with a piece of fabric that someone improvised and glued to that head. This naturally brings up the question: what is this doll doing in a museum devoted to the history of the Holocaust? This doll, which normally would not attract any attention, will have a great deal of importance within this context. Next to it will appear the image of a woman, no longer young, telling her story and her connection to the doll in a rather childlike voice.

Zofia Rosner or Yael – the Hebrew name she adopted after the war – was a little girl during the Holocaust. The Nazis had taken her father in the early days of the occupation, and she and her mother were incarcerated in the Warsaw ghetto. Yael’s mother was connected to the underground and became involved in smuggling activities. She would disappear for several days at a time, leaving the little girl alone. The mother found a doll’s head, and created the doll for her daughter. She sewed on the fabric to make the dress and gave it to the little girl. "You take care of your daughter during the day", she told her. The doll, Zuzia, became Yael’s only companion and she developed a special bond with her. Zuzia was her friend, her confidante, and her family during the lonely and frightening time that she spent alone, hiding in the cellar somewhere in the ghetto. One day, Yael’s mother did not return, but instead arranged for a Polish boy to enter the ghetto and bring out her daughter. The boy put the little girl into a sack with coals and wanted to smuggle her out. On the way, the little girl began to scream: "I forgot my doll". The boy, of course, enraged, said a few choice things to the little girl, but she insisted: "Mothers do not leave their daughters in the ghetto”. The boy decided to return to the ghetto and to fetch the doll. Yael survived, but her story had a sad ending. Her father was murdered and although the mother survived the war, she died shortly afterwards. The little girl reached Israel and the doll became part of her life, part of the memories of her family, part of the past in the ghetto. Her testimony will be shown together with the doll, which she donated to Yad Vashem.

Photographs, taken by a German soldier by the name of Jost who visited the ghetto will be displayed next to the doll. These pictures show scenes of the daily life in the ghetto, of crowded streets with people moving about, of hunger, with children lying helplessly on the sidewalks, people dying of starvation and disease. Next to them, there will be pages from the famous underground archives founded by the historian Emanuel Ringelblum. The “Oneg Shabbat” archives, as they were called, were created at the time of the Warsaw Ghetto, and this collection serves today as one of the most important Jewish sources for documenting the history of the Holocaust. Next to this, we will see part of a film and an interview with another witness. Thus, in one small area of the display and within a short space of time, we will encounter a variety of means and media imparting the story. This actually is an example of the strength of what a museum can offer.

In essence, the museum, when it is being equated with other means, is characterized by the fact that it is multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary, and that it actually utilizes and combines the abilities of each of these channels. It brings together the documentation, the artifact, the cinematic element of moving images, the literary piece, diaries or letters, creations of human beings from the period, works of art – everything that a person is capable of expressing. The combination of all these means – if it is implemented in a proper, intelligent manner – forms the special language that is the axis for building the story in a history museum. The Visitors are actually invited to embark on a journey, a journey of discovery. The further one progresses through the museum on this journey, the more acquainted and connected one becomes as one discovers the various layers of the story. Visitors who set out on this journey are, to a large extent, autonomous. They can decide how deeply they would like to delve, and at what pace they want to progress; they can autonomously select what affects them more; they can also choose what they want to ignore for one reason or another. This special encounter between the visitors and the exhibit and between the variety of dimensions and means presented to them actually creates a unique combination.

A museum is built on two mainstays: on the one hand it provides information and knowledge, and on the other it creates an experiential dimension. Both – the emotive experience and the knowledge – stand side by side. The museum is by no ways a substitute for reference books or textbooks. This very combination of experience and knowledge – if done properly and in the correct manner – can create something deeper. It can produce insight and a deeper perception as well as an emotional commitment, adding dimensions to the story that is being conveyed.

No museum of history, and certainly no museum that deals with the history of the Holocaust, can exist if it does not tell a story. Moreover, any attempt to influence human beings must be based on a human story. The decision as to the boundaries of the story, the period of time and the chapter on which the story focuses, is open, but if the exhibition does not tell a story, it will be no more than a collection of objects. Consequently, a Holocaust museum cannot be an ethnographic type of museum that sheds light on beauty or on the significance of some item or another. The complete conjunction of all these means that come together to build the dynamic of the encounter with the visitor is the secret of the museum's existence.

The overall approach to the planning of the new museum complex of Yad Vashem is determined by Yad Vashem’s character and essence. Yad Vashem is not merely a Holocaust museum. The museum is only part of a broader concept, of a unique entity that constitutes what is actually the Mount of Remembrance. From the outset, the concept was that this mountain would be devoted to dealing with all the dimensions of commemorating the Holocaust, and perpetuating a meaningful remembrance. Consequently, the very foundation of Yad Vashem is documentation. The collection of documents and their preservation for future generations started during the time of the Holocaust by the victims themselves. Yad Vashem continued this tradition and its archive today contains around 60 million pages of documentation, over 200,000 photographs, about 40,000 testimonies gathered in a period of over 50 years, and other material. On this tier comes the layer of research and publications. The Yad Vashem International Institute for Holocaust Studies conducts comprehensive research projects, holds conferences, promotes exchanges of researchers and publishes books of research, memoirs, diaries and special publications of Holocaust era documentation. The last layer – education – connects all the various components of the mountain. The Yad Vashem International School for Holocaust Studies produces educational material, implements teacher training programs in Israel and abroad in 9 different languages, and conducts study days for tens of thousands of students every year.

The Mount of Remembrance has another important role: it serves as the site for commemoration and for contemplation. This stems from a genuine need of the Jewish people and the State of Israel to mourn, to remember, to reflect and to contend with the enormous void that has been created by the Holocaust. Most of the Holocaust survivors have come to Israel, where they constitute an important part of the population and where they played a significant role in the building of the state. Yad Vashem has become the place for collective and individual remembrance and a place that has meaning for the entire Israeli society as well as for every person as a human being, i.e. for all of humanity. At the center of the mountain is the Hall of Remembrance, a simple structure that is familiar to many people, where ashes from the extermination camps were placed. An eternal flame burns within.

The Yad Vashem museum complex is a part of this mountain and is closely integrated into the other layers of documentation, research, commemoration, and constitutes and important part in the educational work. A teacher in a classroom setting can show a film, use photos or invite a survivor to come to talk to the class. The visit to the museum, however, adds a new dimension to the educational activity. If structured properly, the visit to the museum enables the educator to utilize its strengths and to create a meaningful educational process – its advantage being the very combination of information and of the experiential dimension. The genuine educational change and impact can only be accomplished through the experiential dimension, without which human beings cannot really be affected, while the information provides depth to the process and avoids the danger of banalization. It follows that one needs to create a communicative situation, a situation in which visitors open up and are prepared to absorb fragments of experience and of information, and to process them into insights that will remain with them after they leave. The basic concept of the International School for Holocaust Studies at Yad Vashem, which is located on the Yad Vashem campus next to the museum, is to structure the study days by starting with an activity in one of the School’s classrooms, then visit the museum, and finally by returning to the classroom where students will undergo their own process of internalization and processing.

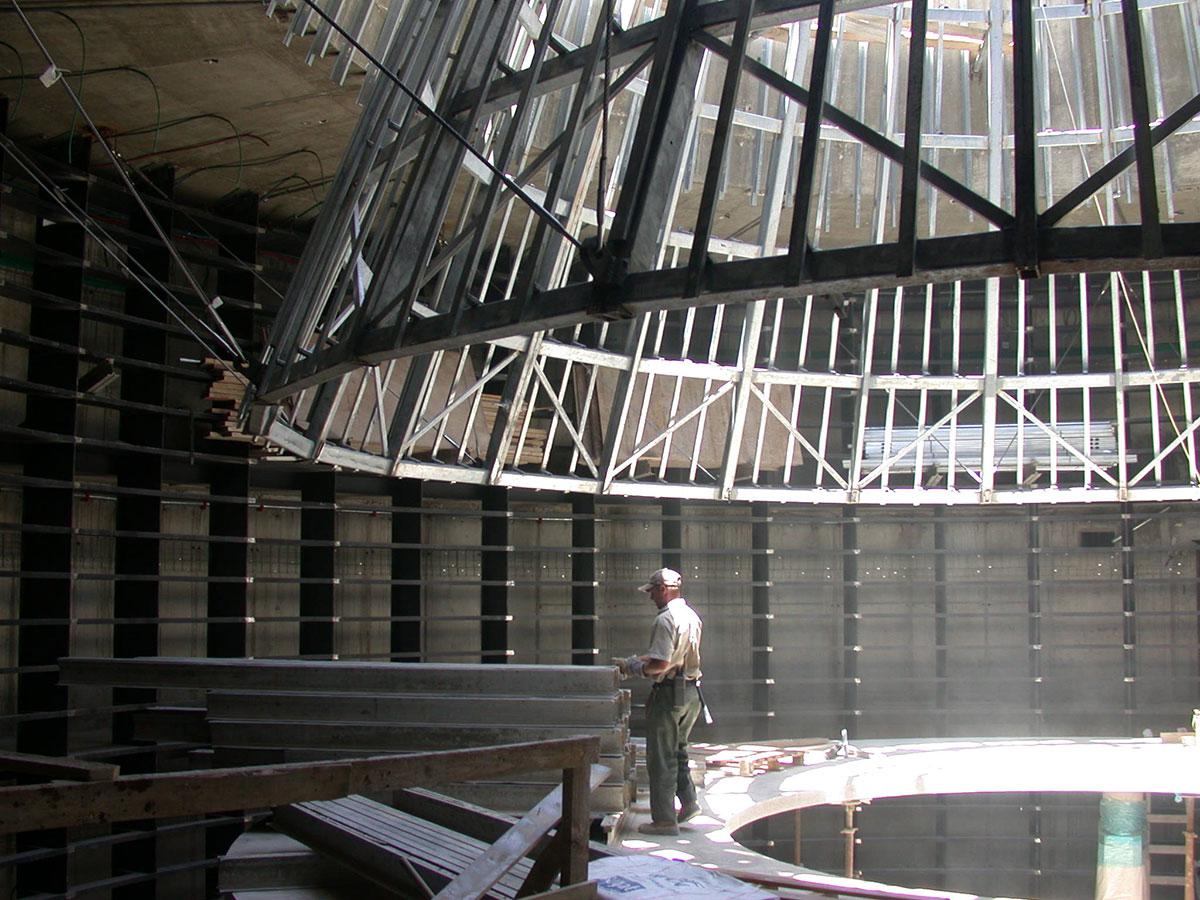

The construction of a new museum complex is part of the 10-year Yad Vashem development plan designed to create the tools for a meaningful transmission of the Holocaust to future generations. The other parts of this development plan are the establishment of the International School and giving priority to the educational work, the construction of a new state of the art archive building, the establishment of the International Institute for Holocaust Research, the computerization of Yad Vashem’s databases and repositories and the construction of a Visitors’ Center to welcome the many visitors to the Mount of Remembrance. (At the turn of the century over 2 million people a year came to visit Yad Vashem.) The museum complex will include a Museum for the History of the Holocaust, a Museum of Holocaust Art, a Pavilion for exhibitions, a Learning Center, a Visual Center and a Synagogue. The new Museum for Holocaust History will occupy over 3,000 square meters and will, for its most part, be situated below the ground. Its 175 meters – long linear structure in the form of a spike will cut through the mountain with its uppermost edge – a skylight – protruding through the mountain ridge. Galleries portraying the complexity of the Jewish situation during those terrible years will branch of this spike-like shaft, and the exit will emerge dramatically out of the mountainside, affording a view of the valley below. It will thus relate to the present and to the museum’s location in Jerusalem. Special attention was given to the integration of the new buildings into the existing features on the Mount of Remembrance so that it will not interfere with the natural surrounding. Generally speaking, the issue of the relationship between museum buildings and the exhibitions they house is a complex one. In our case the architecture and exhibition design were generated by an initial overall concept, in order to guarantee that there would be rapport and dialogue between the building with its pronounced statement and the display and concepts that underpin it.

What distinguishes this new museum that is rising in the center of this mountain? First and foremost, it is the perspective of the entire presentation. As a museum of the Jewish people Yad Vashem presents the story from a Jewish perspective, i.e. from the point of view of the victim. A great deal of the literature and some of the exhibitions around the world present the story from the point of view of the perpetrator, of the generator of the story. Yad Vashem will present the Jewish narrative, emphasizing the Jews as subjects rather than objects in Nazi hands. The displays, presented from a Jewish perspective, will focus on the Jewish reality during the Holocaust. In our view it is impossible to understand the Holocaust and to absorb its meaning, if we do not approach it from the standpoint of the victims. We must examine how they coped with the events, how they understood the events, how they reacted. Our presentation is based on the enormous wealth of Jewish documentation, archives, diaries, testimony, works of art, objects remaining from that period, and the research that came afterwards. It is however not a unilateral view. The story will be complemented by research and documentation about the perpetrators and the environment in which these things happened, about the entire periphery that is now called, in short, the bystanders.

As a museum that focuses on the Jewish narrative, we depict the victims not only as targets for the German plan of the final solution, and therefore do not limit the story to the period of 1933-1945, but begins with a presentation of the Jews before the rise of the Nazis to power and end the story with a chapter that describes the period after the liberation. We have to show the wholeness, diversity and dynamism of the lost Jewish world, the Jews’ lives, their communities and their culture, before we confront the loss. Likewise, it is only natural that a museum that exhibits the Holocaust in Jerusalem cannot limit itself only to the destruction process alone, but needs also to shed life on the Jewish world after the war, telling about the fate of the remnants, the survivors, their lives and their existence after the war. Between these two sections, the story is being told in a number of chapters. The structure of the exhibition in the new Museum for the Holocaust History is based on a story that develops chronologically, and winds around certain themes. On the one hand this structure is chronological, in other words, it follows the timeline in the general context of the Second World War, and on the other hand it contends with a myriad of themes that underpin the story of the Holocaust. The historical structure of the Holocaust is very complex, with, processes occurring simultaneously, and at the same time, with certain things happening in one place at one time and in another place at another time and under slightly different conditions.

A third important point in the planning of the museum’s display is our focus on the individual. This history cannot be described solely from the point of view of the general outline of the important events and great contours of history. The museum will be based on, and come from the perspective of the individual person. It has been said that the story of the Holocaust could be understood only if we would reconstruct six million stories and then connect them all into one structure. If we created a giant pyramid of all the stories, we might, perhaps, begin to understand the history of the Jews in that terrible chapter in history. The point of view of the person who is the individual is essential if we want to contend with this history. We need to look him in the eye, to see him, to get to know him as closely as we can. The human stories and personal exhibits will permit visitors to connect and establish a more intimate relation to the story. I would like to quote the last verses of a poem by the Rumanian born Benjamin Fondane, a Holocaust victim himself, who wrote in 1942:

A day will come, no doubt, when this poem

will find itself before your eyes. It asks

nothing! Forget it! Forget it! It is nothing

but a scream, that cannot fit in a perfect

poem. Have I even time to finish it?

But when you trample on this bunch of nettles

that had been me, in another century,

in a history that you will have canceled,

remember only that I was innocent

and that, like all of you, mortals of this day,

I had, I too had a face marked

by rage, by pity and joy.

An ordinary human face!

The story, as told by us, will begin at the eye level of the individual before the overall evidence unfolds. The individual stories, however, will not add up to a wholeness, unless there will be a combination of the context and the text. In this view, the text is told and elaborated in the story of one person and then another and yet another, and the context is the larger course of events that generates the phenomenon. Therefore we begin the story from the individual text, we move on to the broader context of the overall structure, and then return once again to the individual.

How do we represent the individual? It is our goal to focus on the human story of the individual, on the personal artifact, on the individual picture. Whereas, in the past, we aimed at describing a phenomenon and therefore presented people as symbols, to the extent that they would become icons, today our approach is the opposite. To this day, no one knows the name of the little boy from the Warsaw Ghetto who is depicted on the famous photograph with his hands up in the air. He has become an icon and symbolizes everyone who stood there with him. However, if we knew the name of the boy, where he came from, who his parents were, what home he had, what he read, who were his friends, before he was stood up and had to raise his arms, we would be able to reach a deeper level of understanding. By this token, in the past, when we had a picture and had a positive identification of the person depicted on it, we would refrain from writing his or her name, because we wanted them to represent a phenomenon and not just themselves. Today, we are taking the opposite approach. Now we are seeking the pictures and photographs in which we can identify the person. If we have an inmate uniform and we know who it belongs to and what it’s history is, we will give it preference over an inmate uniform in better condition for which we have no information, that is not connected to a specific story. We will give preference to an object that we can connect with a person and with an event and to retrieve the information in order to piece the story together.

Thus when we present photos from the now famous Auschwitz Album, describing the arrival of a transport of Hungarian Jews from Carpatho-Ruthenia, we will place next to them what remains of a pair of spectacles, of glasses that belonged to Bluma Wallach from Lodz in Poland. She had arrived at the ramp in Birkenau with her daughter, Tula. During the selection, she gave her glasses to Tula for safekeeping. The daughter hung on to the glasses, which were the only remaining item of her mother who was gassed shortly after their arrival at the camp. She somehow managed to hold on to them all along her imprisonment at Auschwitz, and later in Ravensbrück. After liberation she had kept them for 45 years. When she eventually decided to bring them to Yad Vashem “because this is the place they really belong”, as she told us, all that was left was a pile of unidentifiable pieces. But this mass of little parts represents an entire world, a life, a face and a memory. Obviously, one of the implications of this approach is our decision that the exhibition will consist exclusively of authentic materials. There will be no artificial décor or scenery used, and the building blocks will be the genuine artifacts, documents, visuals and works of art. Hence the enormous importance and efforts invested in the collection of items by our curators. A lot of work goes into the reconstruction of the background and story behind each article in the collection.

In the transition between the general phenomenon and the individual tale, we sometimes focus on the story of one event in order to shed light on a larger phenomenon and to contend with its astounding, almost inconceivable components. For example, at the end of the war, as it was clear that Germany was about to lose the war, when its armies were retreating and chaos reigned, the Germans allocated forces to taking the last remaining surviving victims, those hunted, tormented skeletons from the camps, and forced them on what came to be known as death marches. In order to comprehend this phenomenon, we intend to tell the story one of these death marches and to concentrate on the story of a group of women. They were about one thousand women at the beginning of this forced march. We have their names, the entire course of their journey and the places they passed through. As they were marched they encountered different people with differing attitudes. In some places they were helped by the locals, others watched and remained silent, and then there were places in which dozens or hundreds of these women were murdered. And we will show pictures of these women – those who survived and those who perished – and accompany them by the testimony of a survivor who tells the story of these women, and by an object that remains from this terrible journey. This link by which we connect to the story and, for an instant, march along with these women, enables us to focus on one limited moment, and to attempt to reach a deep insight of the entire phenomenon. This is the foundation of the basic structure of the materials with which we build the story.

The decision to include the new Hall of Names an integral part of the new Museum of Holocaust History is very telling. The Yad Vashem Hall of Names houses the single largest database of information about the victims of the Holocaust. The repository of Pages of Testimony contains forms filled out by survivors and family members commemorating loved family members, relatives and others murdered in the Shoah. These forms – each representing an entire life that was lost – contain biographical details such as: the name of the victim, his or her date and place of birth, the place of residence before the war, the profession, the parents’ and spouse’s names, where and when during the Holocaust they perished and a picture – if any survived. Thus the visitor to the museum will actually enter this archive where these pages are kept, where the repository of the documentation of the events is preserved constituting the foundation on which we are trying to reconstruct the complex reality. This will conclude the major part of the museum depicting the destruction of the European Jews, and before the visitor will move on to the last section, this will create room for one more contemplation, one more reflection.

As our visitor journeys through the museum, we expect him to reflect on the events. This process may contain some risks. We must therefore make sure that the narrative is historically accurate, the product of the most updated research, and based on the most reliable materials. There cannot, and there should not, be any hidden messages or self-righteous, judgmental or instant conclusions that we want to score. We are very careful to assiduously avoid any form of hidden insinuations that we want to transmit. Nevertheless, the question arises, what do we want to achieve?

First and foremost – and this is actually the strength of the museum – we want to create empathy, you might even say identification of the visitor with the subject of the story, with the person who was a victim of the Holocaust, who suffered, who was tortured, who was murdered, whose loss still leaves an open wound and a vacuum that need to be filled. If such empathy is generated, if there is a genuine dialogue, then an experience will have been created that visitors will take with them when they leave the museum. If the experience is meaningful, they will be able to attain another level of personal commitment, even if these visitors are not personally connected to the story.

Attaining responsibility or commitment is how the museum can make the present link to the past. It would be a failure on our part if we created a museum that would deal with an episode that is connected only to the past, that is a closed chapter in history. It is not our intent to confine the visitor into a bubble, totally disengaged from his or her identity, life or being. It would actually be impossible, since the Holocaust is connected with our present and bears upon our self-understanding as human beings. Professor Israel Gutman, one of the greatest Holocaust historians and a survivor who personally experienced the horrors of the ghetto and the camps, once said, “The Holocaust refuses to become just another chapter in history.” It is unknown how much longer the Holocaust will refuse to be just another chapter in history, but at this stage, our success will be measured by the extent to which the present will accompany us as we explore the various parts of this voyage of discovery in the museum. This relevance of the present is what the visitors experience and what they see and learn which bears on their daily lives and their behavior in the future. If they leave with the feeling that these issues are relevant to their identity and their lives, they will assume a responsibility for, maybe even a commitment to, their conduct as human beings.

For us, members of the Jewish people, this commitment is extremely significant. It is a commitment to our continued existence as Jews, to a continuation of our history, our values and culture. It is a responsibility that this great stream with a variety of outlooks, understandings and beliefs, which has contributed to civilization throughout the ages, will continue to exist. It is the convergence of these variegated streams that forms Jewish heritage, Jewish history and Jewish values. If responsibility to the continuation of this existence is to be attained, we must contend with the Holocaust not just as a trauma in our past, but also as an engendering phenomenon with which we have to struggle and from which we learn and with which we build our collective identity.

The Holocaust has meaning not only for Jews. It touches upon the fundamental and most basic values upon which human society rests. These values begin with the Ten Commandments, with “Thou shalt not kill”, with the teachings of the prophets, the values of the autonomous right of a person to his life, his property, his creation – the basic values that were forged on Mount Sinai and accompanied us in Judaism, and were later adopted by Christianity, and which the Muslims imbibed from – the message which became the basis for the universal existence of man. These are the values that civilization has built over the generations and which were in danger of collapsing or broke down completely during the period of the Holocaust. It is clear that extreme evil is something that accompanies our lives on a fundamental level. The goal of the Nazis was to build a new morality based on racism, on the destruction of the values of western culture, the values of the French Revolution. This structure of values which was formulated back in the days of the prophets, of Greece and Rome, which we thought was stable and sound, was about to break down and collapse. This is the pivotal point with which every sensitive person must contend, which compels us to reach some kind of responsibility and commitment. This process will be possible only if empathy is created between the visitor and the components of the story. Then people will take with them their conclusions, which are connected to the basis of our very existence as a human society.

Visitors who complete the tour will exit the museum onto a balcony that overlooks the Jerusalem landscape in which the museum is located. This scenery perhaps gives a bit of serenity and the opportunity to contemplate, but it also shows that life around it goes on. We do not, under any circumstances want anyone to leave with an uplifting or redemptive and expiating experience. We have been trying all along to distance ourselves from kitsch and from extremism. The statement, which we strive to realize, is more introverted, subtle and modest, and it relates to the nature of man in the context of this story. When we step outside this context, we understand how the Mount of Remembrance, of which the museum is a part, integrates into the life experience in Israel, and then it takes on significance in the circle of Judaism, and finally how it constitutes a profound significance as a kind of warning beacon to the entire world. And this process occurs because the Holocaust is not perceived as a chapter in history, but rather as a component in the building of our culture, in the shaping of our existence. And thus the Mount of Remembrance, which is located in Jerusalem, the city in which the Prophets walked and bequeathed to the world the basic values of our culture, has also become a warning beacon against extreme evil. But this is not a silent beacon. It is one that conducts a constant dialogue, a mountain with all the strata that build culture and memory, of which the museum is a part, that conducts a dialogue with the visitor, between the visitor and himself, between the visitor’s experience in the present and – perhaps through his thoughts and conduct – the future.