We stand now seventy years after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. This uprising was born out of the severe oppression suffered by Jews in the ghetto under German occupation. At the same time, the mere fact of its occurrence shattered the limits of the imagination.

The situation in Warsaw, the largest ghetto in Europe, was completely different from the situation in any other ghetto. Warsaw was the city with the largest Jewish population in prewar Europe; the number of Jews living in the city was rivaled in the rest of the world only by New York. At its height, almost half a million Jews were imprisoned in the Warsaw ghetto.

Then, during fewer than 60 days during the summer of 1942 (between two important Jewish holidays, Tisha B'Av and Yom Kippur), almost 300,000 of the Jews in the ghetto were deported to the death camp of Treblinka; this aktion 1 is referred to as "the Great Aktion" or the "Great Deportation".

Although the youth movements had been aware of the murder and deportation of the Jews beginning as early as the fall of 1941, most of the residents of Warsaw did not believe that anything similar could ever happen in a city that was the capital of Jewish Europe. However, with the Great Aktion, they were proved wrong.

This aktion was the impetus for the realization and, more importantly, the internalization, that the murders and deportations that were occurring elsewhere in occupied Europe could happen in Warsaw, as well. This understanding, in turn, was the impetus for the creation of the ZOB (Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa, or Jewish Fighting Organization), on July 28, 1942.2 By October, 1942, the ZOB included members of various youth movements such as HaShomer HaTzair, Dror Freiheit, Gordonia, Akiba, the Bund, etc. A parallel fighting organization, the ZZW Zydowski Zwiazek Wojskowy, or Jewish Military Union), comprised of youth members from the opposite side of the political spectrum – Betar and the Revisionists – had also organized and was ready to fight. The two organizations cooperated to an extent, and fought the Germans in parallel, but never unified.

Of course, there were many impediments to organizing armed resistance. The Jews in the ghetto were confronted with awful dilemmas such as risking collective punishment and endangering their families, and using monies for weapons that might otherwise be used for food or to save Jews hiding outside the ghetto.5 In addition, the youth movements were idealistic groups which had, until the summer of 1942, been involved primarily in education and social welfare. Most of their members were still young – in their teens and early twenties. Just coming into their own, many of them had been preparing for immigration to Palestine – they were very unlikely candidates for armed resistance against the Germans. Moreover, most of the members of the ZOB, the larger fighting group, had absolutely no military training whatsoever.6

In addition to their total lack of training, the ZOB had few weapons with which to fight the Germans. Their first pitifully small cache of weapons – five pistols and eight hand grenades – was seized on September 3, 1942. On the same day, two of the top ZOB leaders, Shmuel Breslaw and Yosef Kaplan, were arrested and killed. The ZOB was left crippled and demoralized, and without any weapons at all.7 Contact with the Poles of the Home Army, or Armja Krajowa, a Polish underground militia, ultimately yielded some revolvers and ammunition, but the ZOB continued to suffer from a lack of suitable weaponry. The fighters relied heavily on homemade Molotov cocktails.

The situation of the ZZW was slightly different because of the personal friendships between ZZW members and Polish officers that existed from the beginning of the war. The ZZW, like the ZOB, used revolvers as the standard personal weapon, but were able to smuggle a few heavier weapons, including submachine guns and a machine gun, into the ghetto through a tunnel they had dug.

Despite all these obstacles, these young, mostly untrained, unarmed prisoners of the Warsaw ghetto determined that they would fight back when the Germans came to liquidate the ghetto.

The first test of the fledgling resistance came on January 18, 1943. The ghetto had been quiet for months; the Germans had not deported any Jews in a mass aktion since September, 1942. Suddenly, though, a large company of SS men appeared in the ghetto. The residents of the ghetto believed that the Germans intended to deport all the approximately 50,000 Jews remaining in the Warsaw ghetto at that time. Having learned from the experience of the Great Aktion during the preceding summer, many of the Jews went down to bunkers they had built, and sought refuge there. The Germans, frustrated, began to snatch people indiscriminately from the streets, but they had a difficult time.

Up until that point, the Jews had been passive, unsuspecting prey for the Germans, who rounded them up easily. But now, with the Jews in shelters, the Germans were thwarted.

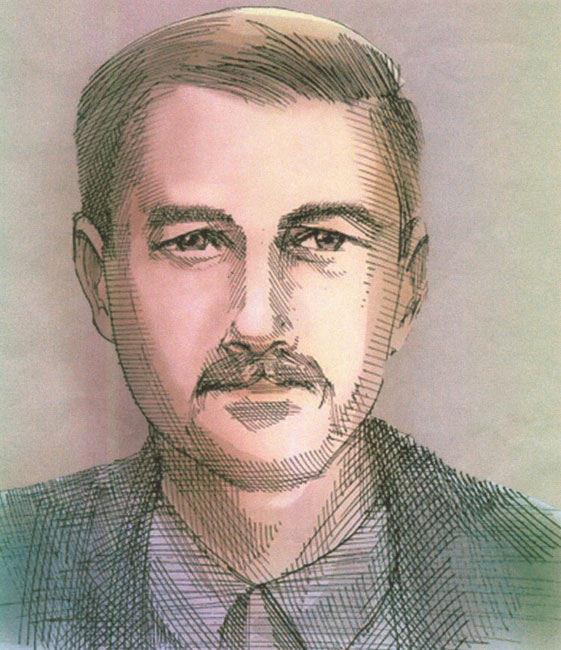

A group of fighters under the leadership of Mordecai Anielewicz, who headed the ZOB, seemed to have been caught in the German's net, and was forced into the street with the rest of the Jews being pushed and shoved towards the Umschlagplatz. At a signal from Anielewicz, the fighters pulled concealed guns out of their pockets and fired at the Germans. In another location in the ghetto, Zivia Lubetkin's and Zecharia Arnstein's fighting groups used different tactics, ambushing the Germans in the street from the windows of apartments above. The Germans retreated. Many Jewish fighters were killed, but the first salvo had been fired. This uprising came to be known as the "January uprising." The importance of the January uprising was in the sudden change of behavior – both of the Jews and of the Germans. The moment the Jews pulled out guns, they turned from objects into human beings; human beings who could challenge the Germans. For their part, the Germans' scorn of the Jews and their inflated self-confidence instantly evaporated; after January, the German troops were afraid to enter bunkers where they might meet with armed resistance.

Today, historians believe that the Germans did not intend to finally liquidate the 50,000 Jews that were still left in the ghetto; it seems that the goal of the Germans was more limited and was only to deport 8,000 Jews who had no papers and were "illegally" in the ghetto.8 Nevertheless, when the aktion ended after only four days, the population of the ghetto believed that an incredible victory had been achieved and that the Jews had repulsed the Germans. The Germans were able to round up "only" 5,000 Jews from the ghetto in January. The final, total annihilation of the Warsaw ghetto had not come to pass. Zivia Lubetkin wrote,

The January uprising had far-reaching consequences even though not many Germans had been killed. We had fired our very first shots against the enemy. The Jews began to realize that it was not only possible to kill Germans, but to remain alive afterwards as well. Moreover, the uprising put a stop to the Aktion. This brought about a sharp change in the psychology of the Jewish community. People who cooperated with the Germans began to fear us…. The attitude towards us on the Aryan side also underwent a fundamental change. They now regarded us with what they called, "trust and respect." They attached great importance and value to the fact that we dared to resist the Germans with so few weapons. Our arsenal grew after the January revolt. 9

In addition, the fighters established themselves as an alternative to the Judenrat; no longer would the Jews of the ghetto follow the orders of the previous leadership. A new authority in the ghetto had been created.

As Yitzhak Zuckerman said, "the January revolt made the April revolt possible."10 It was an indispensable step in preparing the fighters, as well as the Jews of the ghetto, for the larger uprising in April, 1943.

In the interval between January and April, 1943, the population of the ghetto worked feverishly to set up subterranean bunkers and hiding places with stores of food, water, and in some cases electricity, in order to prepare to hold out against the Germans for weeks or even months. Meanwhile, the strategy of the fighters was not to engage the Germans in open face-to-face combat, but to ambush them from the windows of buildings that looked out onto streets and courtyards where German soldiers were likely to pass. There were only a few hundred fighters in total.11

On April 18, 1943, the ghetto received reports that German and Ukrainian troops were massing near the ghetto walls. It was Passover eve, the holiday on which the Jews celebrate the exodus from Egypt, considered a festival of freedom. The residents of the ghetto abandoned their celebrations. They did not sleep that night; they packed their belongings and provisions and went down into the bunkers.

In the early morning of April 19, 1943, the German forces penetrated the ghetto. They walked in a seemingly endless procession, and behind them were Waffen-SS units on motorcycles, with tanks, light cannons and armored vehicles.

Simha ("Kazik") Rotem, one of the ZOB fighters12 understood, seeing the Germans, that the battle was lopsided. "What force did we have against an army, against tanks and armored vehicles? We had nothing but pistols and grenades."13

Yet, the Jews had the element of surprise on their side, and for the first few days of the uprising, they managed – with their almost nonexistent arms – to repel the mighty German army. What follows is Zivia Lubetkin's testimony at the Eichmann trial – though it is long, it is worth reprinting much of it here.

When the day dawned, I was standing in the upper part of this building…and I saw the thousands of Germans who were surrounding the ghetto - with machine guns, with cannon - and thousands of them, with their weapons, as if they were going to the Russian front. And there we stood opposite them - some twenty young men and women. What were our weapons? Each one had a revolver, each one had a hand-grenade; the entire unit had two rifles, and in addition we had homemade bombs, primitive ones, the fuse of which had to be lit by means of a match, and Molotov Cocktails.

…We knew that our end had come. We knew beforehand that they would defeat us, but we also knew that they would pay a heavy price for our lives. Indeed, they did. It is difficult to describe, and there will surely be many who will not believe it, that when the Germans came near the foot of one of our strong points and passed by in formation, and we threw the bombs and the hand-grenades, and we saw German blood pouring in the streets of Warsaw, after so much Jewish blood and tears had previously flowed in the streets of Warsaw - we felt within us great rejoicing and it was of no importance what would happen the following day.

There was a great rejoicing amongst us, the Jewish fighters. And behold the miracle: the great German heroes withdrew in tremendous panic in the face of the handmade Jewish hand-grenades and bombs. And we noticed, one hour later, how a German officer was spurring the soldiers on to go to battle, to go out and bring in the wounded, and not one of them moved and they abandoned their wounded men whose weapons we subsequently collected.

And so it happened, that on the first day we, the few - with our scant arms - drove the Germans out of the ghetto. Naturally they came back. They were not short of ammunition, of bread and water as we were. And they returned. They returned that day, for a second time, in greater strength; with field-guns and tanks, and we with our Molotov Cocktails also set a tank on fire. […]

It is difficult for me to describe life in the ghetto during that week, and I had been in this ghetto for years. The Jews embraced and kissed each other; although it was clear to every single one that it was not certain whether he would remain alive, or it was almost certain that he would not survive, nevertheless that he had reached the day of our taking revenge, although no vengeance could fit our suffering. At least we were fighting for our lives, and this feeling lightened his suffering and possibly also made it easier for him to die.

I also remember that on the second day - it was the Passover Seder - in one of the bunkers by chance I came across Rabbi Meisel. […] when I entered the bunker, this Jew, Rabbi Meisel, interrupted the Seder, placed his hand on my head and said: "May you be blessed. Now it is good for me to die. Would that we had done this earlier."14

Ultimately, the Germans brought in a specialist to subdue the uprising. General Jürgen Stroop, who had experience in partisan warfare, determined that he would not fight the Jewish "bandits" head to head. He recognized that the German soldiers were afraid of the Jewish fighters, and were losing their discipline.15 He also understood that most of the population was holed up in bunkers that he would have to destroy. For this reason he determined to use his long-range weapons and flamethrowers to pulverize the ghetto buildings and burn the ghetto down. He torched the ghetto, turning it into a sea of flame and rubble, as can be seen in many of the photographs16 he collected and turned into an elegant album to document his triumph, accompanied by a report, entitled "Es gibt keinen jüdischen Wohnbezirk in Warschau mehr" (the Jewish quarter in Warsaw no longer exists).

A significant episode in the ghetto uprising was the so-called "battle for the flags"17 that took place in the northern ghetto on Muranowska Street. The ZZW, under the leadership of Pawel Frankel, had managed to hoist two flags at the top of some of the higher buildings on that street: the blue-and-white flag of the Zionists, and the white-and-red flag of Poland, which had been smuggled into the ghetto through the sewer. The flags could be seen from outside the ghetto walls, and communiqués concerning them were communicated to the Polish underground and broadcast over Polish radio (certain sections of these communiqués were even picked up by the New York Times). The flags flying over the ghetto sparked the imagination and the enthusiasm of the local population; this was the ultimate affront to the Germans. The Germans understood this and made Muranowska Street a primary target, bringing in ever heavier artillery and increasing manpower in order to take the flags down at any cost.

Yet the fighters were determined to do whatever it took not to give up the flags – they continued to wave over the ghetto for almost four days. Finally, by Friday, April 23, 1943, after tanks and artillery had pounded the buildings on Muranowska Street to such an extent that the entire street shook, the flags ceased to wave, having been shot to pieces.18

On the same day, April 23, 1943, a letter written by Mordecai Anielewicz, leader of the ZOB forces, was smuggled out of the burning ghetto and left in the Jewish cemetery for Yitzhak Zuckerman:

It is impossible to put into words what we have been through. One thing is clear, what happened exceeded our boldest dreams. […] The dream of my life has risen to become fact. Self-defense in the ghetto will have been a reality. Jewish armed resistance and revenge are facts. I have been a witness to the magnificent, heroic fighting of Jewish men in battle. Mordecai19

When the Warsaw ghetto uprising began, there were only a few hundred fighters and approximately 50,000 Jews still living in the ghetto. While the members of the resistance organizations fought, the rest of the Jews in the ghetto took refuge from the Germans in underground bunkers and hiding places, thus contributing to the resistance in a more passive way. The Germans were forced to expend a huge amount of manpower in order to find the bunkers, drag out their inhabitants, and then destroy the shelters so that they could no longer be used to ambush the German forces.

"The will to resist has been sparked among thousands of men and women, elderly people and children, a will which conquers the natural anxiety and the fear of death and hardship. The masses have understood that by resisting surrender they are fighting the enemy in a unique way, hindering his deeds of destruction… The Germans were forced to conquer every single shelter and bunker with full force of arms.20

In order to locate the underground bunkers the Germans made use of dogs, listening devices, and informers. Soon, the entire ghetto was aflame. Houses collapsed, people hiding in bunkers underneath them were killed, and everyone still hiding found it difficult to breathe in the unbearable heat. Yet, despite all these horrors, the residents of the ghetto continued to hold out for as long as they could.

This is one of the reasons that the Warsaw ghetto uprising is considered to have been so successful – the armed fighters had the backing of the rest of the ghetto, who cooperated with them in order to resist the Germans to the greatest extent possible.

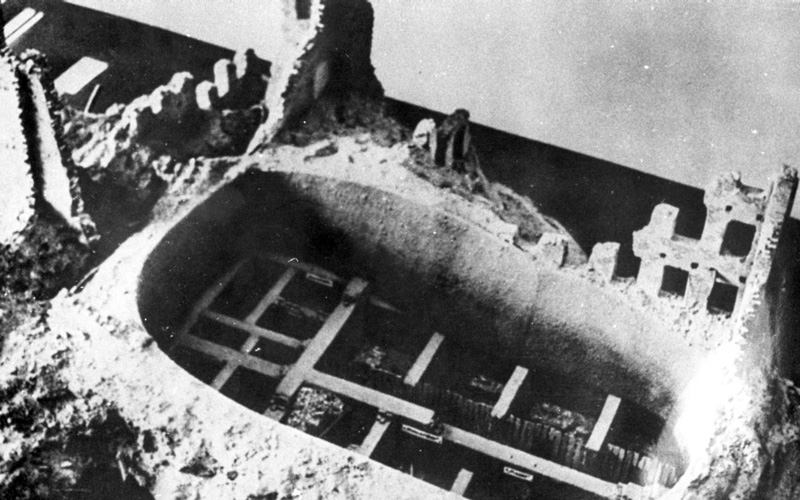

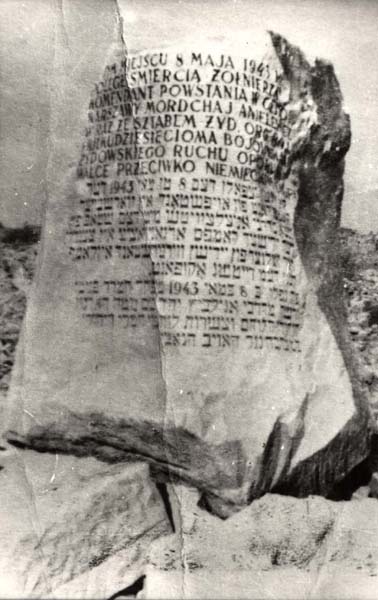

On May 8, 1943, the Germans located the command bunker of the ZOB forces at 18 Mila Street and began to pump in poisonous gas. There were over one hundred fighters in the bunker at the time, including Anielewicz. Members of the resistance, including Arie Wilner, called for the fighters to take their own lives so as not to fall into German hands. Most of them did so. The Germans blew up the bunker, trapping everyone still inside.

As a final dramatic and symbolic act, Stroop dynamited Warsaw's most beautiful prewar synagogue, the Great Synagogue of Warsaw, located on Tlomackie Street. He saw this as an allegory for the defeat of Warsaw Jewry, and proclaimed through this act that he had put the ghetto uprising down. Yet his troops continued to meet with sporadic resistance from isolated bunkers in the ruins of the ghetto for a number of months, even as late as the fall of 1943.

Conclusion

Ultimately, most of the Warsaw Ghetto fighters were killed in battles or during the months following the uprising. Those who did not fight were captured and sent to death and labor camps; most did not survive. Historians point out that no more than a handful of German soldiers were actually killed in the uprising. So why is the uprising so significant in our eyes? Why, seventy years later, do we continue to put the fighters on a pedestal and call them heroes? It wasn't because of their military acumen or because of the way they fought – it was the mere fact that they fought at all. The military success or failure of the uprising is not the whole story. On the 25th anniversary of the Warsaw ghetto uprising in 1968, Yitzhak "Antek" Zuckerman was interviewed by the Israeli press. He had this to say about the significance of the uprising:

"I don’t think there’s any real need to analyze the Uprising in military terms. This was a war of less than a thousand people against a mighty army and no one doubted how it was likely to turn out. This isn’t a subject for study in a military school. Not the weapons, not the operations, not the tactics. If there’s a school to study the human spirit, there it should be a major subject. The really important things were inherent in the force shown by Jewish youth, after years of degradation, to rise up against their destroyers, and determine what death they would choose: Treblinka or Uprising. I don't know if there's a standard to measure that." 21

- 1.An aktion is a roundup of the Jews, generally for deportation.

- 2.A previous body, called the "Anti-Fascist Bloc", was established earlier, but quickly became defunct.

- 5.The initials of Betar stand for "Brit Yosef Trumpeldor", or the covenant of Yosef Trumpeldor. Trumpeldor was a fighter who had lost one arm in previous battles, and died defending Jewish settlements at Tel Hai in 1920 against Arabs. He is quoted as having said, "It is good to die for our country," though the Jews had no country yet. Betar was founded by Ze'ev Jabotinsky in Riga, Latvia, in 1923, and came to be associated with armed struggle by the Jews in then-Palestine, as well as in Europe.

- 6.See another article in this issue of the newsletter for the dilemmas involved in resistance.

- 7.In contrast, some members of the ZZW had fought in the Polish army and had military training; others had been trained in Poland in cells of the Irgun Tzva'i Leumi before the war. See https://www.etzel.org.il/english/ac16.htm, accessed July 18, 2013.

- 8.See Yisrael Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, 1939-1943: Ghetto, Underground, Revolt, trans. Ina Friedman (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982), p. 360.

- 9.Yisrael Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, pp. 307-308.

- 10.Lubetkin, In the Days of Destruction and Revolt (Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House/Ghetto Fighters House, 1981), pp. 164-165.

- 11.Gutman, The Jews of Warsaw, p. 320.

- 12.Gutman, in The Jews of Warsaw, gives the number of fighters at about 750; 500 in the ZOB and 250 in the ZZW. Gutman, p. 365.

- 13.See the interview with Kazik in another article in this newsletter.

- 14.Kazik (Simha Rotem), Memoirs of a Ghetto Fighter, ed. and trans. Barbara Harshav (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994), p. 33.

- 15.Eichmann trial transcripts, accessed November 2, 2012.

- 16.Moshe Arens, Flags Over the Warsaw Ghetto: The Untold Story of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House, 2011), p. 205, p. 222.

- 17.An online exhibition of many of these photographs can be seen.

- 18.The battle of the flags was immortalized by Israel's first Foreign Minister, Moshe Sharett (later, Israel's Prime Minister) in the speech he gave to the United Nations when Israel joined that body in 1949. Sharett spoke of "this blue-white flag…that was unfurled over the walls of the Warsaw ghetto in the desperate uprising…" The speech, containing this reference, has appeared on the Israeli 20 shekel note since 1998.

- 19.Arens, Flags Over the Warsaw Ghetto, p. 228.

- 20.Yitzhak Arad, Yisrael Gutman and Avraham Margaliot, (eds.), Documents on the Holocaust (Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1981), pp. 315-316.

- 21.Hersh Wasser, in Melekh Neustadt, the Destruction and Rebellion of the Jews of Warsaw, p. 190, accessed July 18, 2013.

![Mordechai Anielewicz 1919 [1920]-1943 Mordechai Anielewicz 1919 [1920]-1943](https://www.yadvashem.org/sites/default/files/3308_97.jpg)