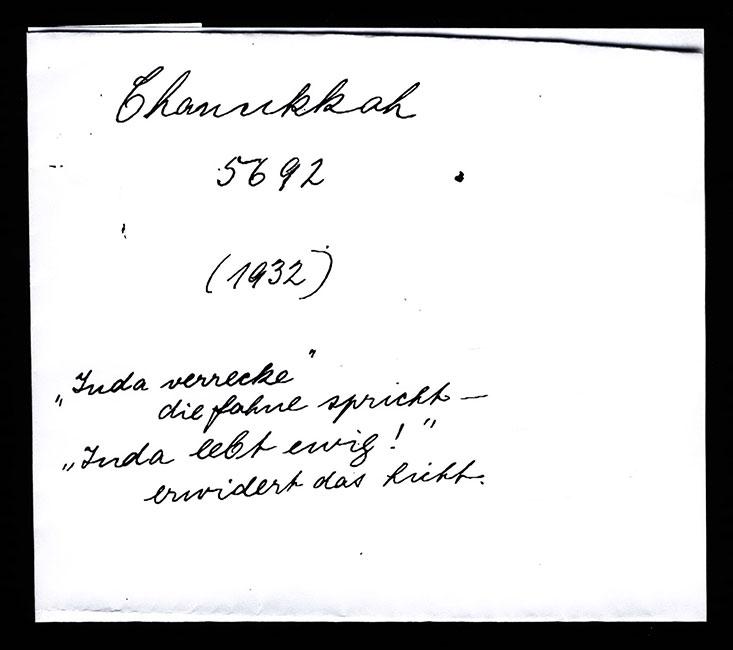

On it Rachel Posner has written what translates as:

"Death to Judah"

So the flag says

"Judah will live forever"

So the light answers.

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, 1486/1431

Yad Vashem Artifact Collection

Donated by Alberto Corcos, Herziliyah, Israel

Observing the Jewish laws and festivals with all their accompanying traditions and customs was one facet of how Jews struggled to maintain their human spirit in the face of persecution and death during the Holocaust. Many found ways to celebrate the Jewish holidays and to observe aspects of Jewish law even under the horrific conditions of the camps and ghettos, in hiding and under false identities.

The Jewish festivals center around historical events – for example, the Exodus from Egypt or the salvation of the Jews in Persia by Queen Esther and Mordechai – as well as themes such as redemption and repentance. This creates a cyclical thematic calendar that is confronted by the religious celebrants, posing the question of how the holiday, its ideas and teachings relate to their lives and the reality in which they find themselves.

Midrash is a Jewish form of biblical interpretation; it responds to contemporary problems and crafts new stories, making connections between new realities and the ancient biblical text. Through artifacts, writings and works of art, it is clear that during the Holocaust many Jews drew on the midrashic tradition and reimagined traditional Jewish texts and traditions to reflect the conditions under which they were living and the traumatic experiences they had undergone.

This series of four blogs examines some of these themes that became so very pertinent to Jewish people caught in the crucible of the Shoah:

Part 1: Then as Now

One recurring theme of Jewish midrashic tradition during the Holocaust is variations on "Bekol dor vador" (In every generation), which situates the Holocaust within Jewish history, in the words of the Passover Haggadah: “In every generation they rise up to kill us, but the Holy One, Blessed be He, saved us from their hands." Although the idea of being perpetually attacked by generations of antisemites seems hopeless, comparing the Nazis to historical enemies of the Jewish people actually presented a message of hope: Just as the previous enemies were defeated, so, too, will the Jews prevail over the Nazis.

The point is explicitly made by the inscription on the reverse of a photograph of a menorah in the window with a Nazi flag in the background during Hannukah 1931 in Kiel.

"Death to Judah"

So the flag says;

"Judah will live forever"

So the light answers.

The owners of the menorah believed that the Hanukkah light, which recalls the victory over the Syrian Greeks, will also prevail over the Nazis who had recently become the largest faction in the Reichstag when the photo caption was written in 1932.

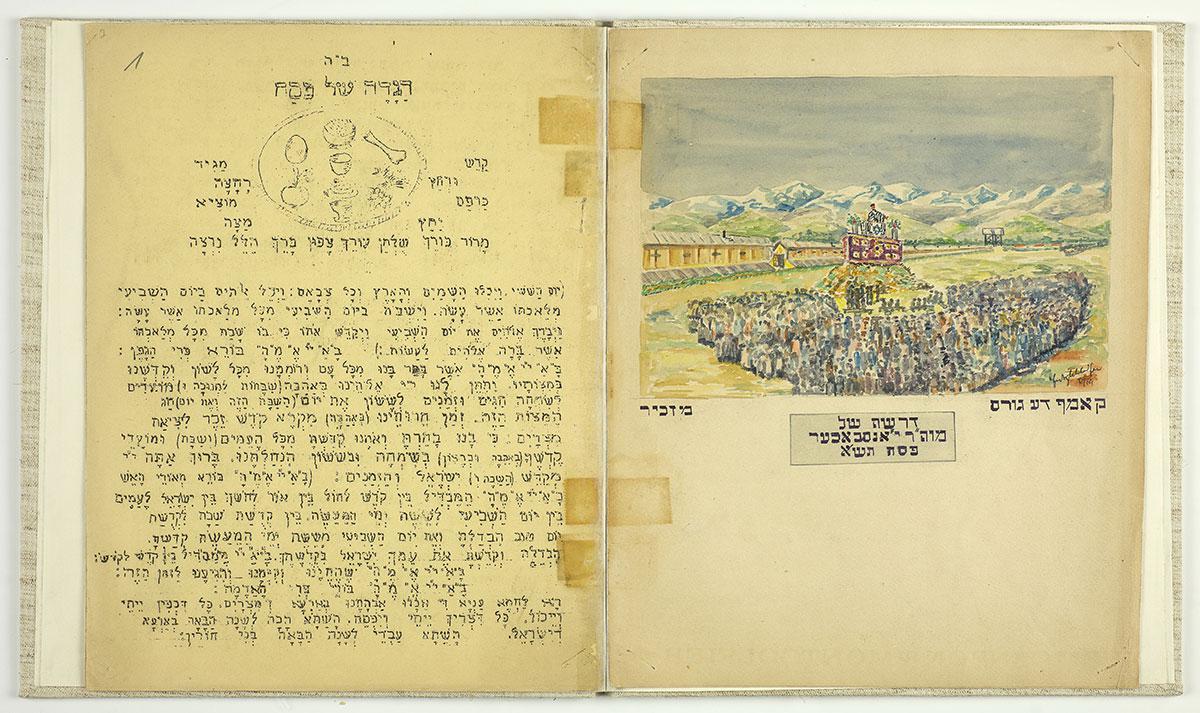

Dr. Pinhas Sigmund Rothschild discussed how the distinction between "now" and "then" became blurred in the days leading to Passover 1941 in the Gurs internment camp in southwestern France. He recalled how the themes of freedom associated with the holiday both gave hope to the Jews enslaved in the camp and provided them with a new depth of understanding of Passover itself.

"At the time, celebrating the Passover holiday in the Gurs camp, we felt as if a refreshing breeze from the Promised Land had descended upon us via the desert: 'By the strength of His hand, God took us out from the house of slavery.'… Before Gurs, we had led a carefree existence in the Diaspora, and had not attempted to truly understand or remember the miracle of the Exodus from Egypt – from slavery to freedom. Now, it was as if that which befell our nation in those distant days touched us and became part of our everyday existence. Then as now: the reality and the expectations. We vacillated between the hope for freedom and the hardships still waiting for us, as we began to prepare for the holiday week in the camp."

This blurring or blending of past and present was also expressed on the occasion of the Purim holiday (c. 1946) by Holocaust survivors in the Landsberg DP camp in Germany when they made a mock-tombstone for Haman (the antagonist of the Purim story who had tried to annihilate the Jews in the ancient Persian empire) and Hitler.

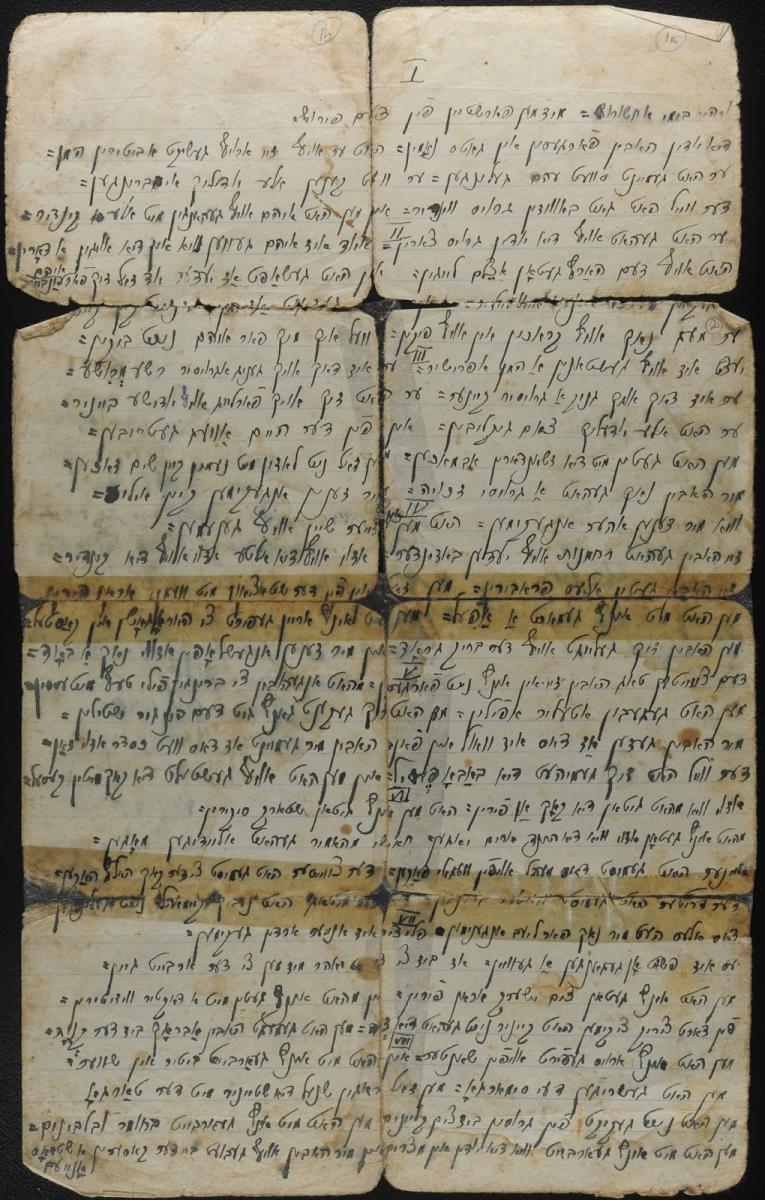

Comparisons between the Purim story and the Holocaust were made during the Holocaust period as well. In 1943 at the Ilia camp in Transylvania, Zvi Hershel Weiss handwrote a text in Yiddish, combining the story in the Book of Esther with the story of the inmates. He wrote the text in order to uplift the mood of his fellow Jews imprisoned alongside him and recited it using the traditional Purim cantillations.

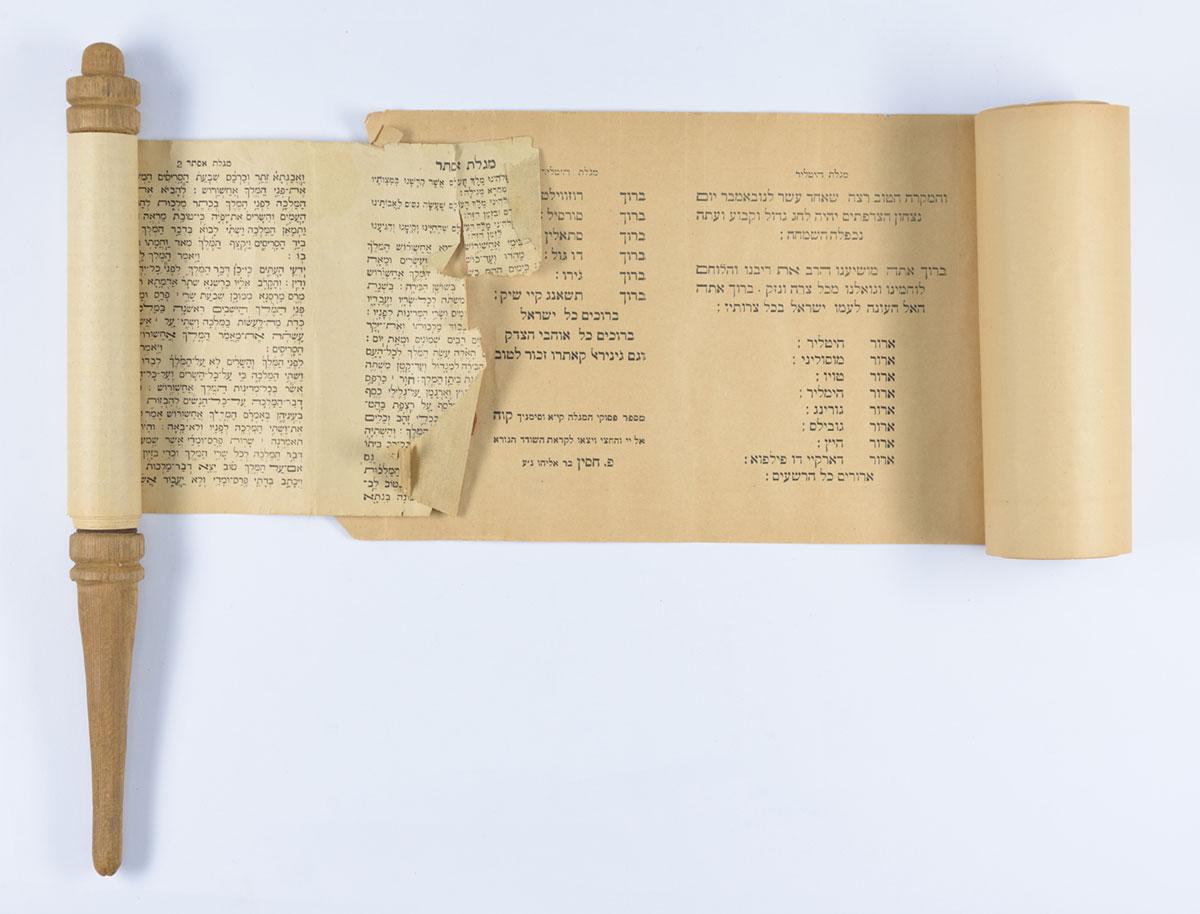

A similar document is the “Megilat Hitler,” written in Casablanca, Morocco in 1944. Spread over seven chapters and written in the style of Megillat Esther (Scroll of Esther), Prosper Hassine, a scribe and teacher in Casablanca, related the events of the Holocaust, from the rise of Hitler to power, through the occupation of Europe and climaxing with the murder of the Jews and the plunder of their property. The final three chapters, written after the liberation of Morocco, are dedicated to the history of North African Jewry and their liberation by the Allies.

The events related in Megillat Hitler parallel the events of the traditional Megillat Esther and reflect the sense that the Jewish people had once again experienced what the Jews of Shushan experienced when Haman set out to destroy the Jews of the Persian Empire. However, in spite of the similarities, Hassine stresses in his preface to Megillat Hitler that it is not a story of joy, since it does not have a happy end. He writes that the Megillah should be read with a serious demeanor while remembering the victims.

Other examples showing how Jews adapted prayers or addressed challenges posed by the Holocaust in sermons and through art will be discussed in upcoming blogs in this series.