In 1941, after the German invasion of the Netherlands, 15-year-old Tsofia (Fieke) Langer-Asscher was forced to leave her school in Groningen and move with her mother Clara to Amsterdam, where she studied at an art school established for Jewish children. From March 1943, however, she was forced into hiding under a false identity in Christian homes in the Friesland region of the northern Netherlands with the help of the Dutch underground. Despite her difficult circumstances, she continued to paint during this period. "I felt that I brought danger with me wherever I went, because I was the Jew who, at any address that opened the door for me, was like a contagious disease," she said in her testimony. "People who theoretically could have lived a fairly normal life chose otherwise, and took an enormous risk."

Tsofia's creations – which feature fairy tale characters at a time when she faced terror, loneliness and uncertainty regarding the fate of her family – are part of a new exhibition, "An Anchor in the Darkness: Creating Art in Hiding during the Holocaust," which is part of Yad Vashem's series of ready2print exhibitions.

"Mortal danger sometimes arouses in a person a spiritual greatness and awesome creative powers," explains Yad Vashem's Museums Division Director Vivian Uria. "During the Holocaust, in the darkest days of the history of humanity, there were Jews who created in hiding – in forests, basements, attics, bunkers, and concealed apartments. The strong need to create and express their experiences in such a harsh reality, mostly through improvisation of creative materials, and the wish to document the tragedy that befell their people testifies more than anything to the power of the human spirit."

The exhibition focuses on works created in the unique circumstances of hiding – often for extended periods of time in which the person was trapped both in the hiding place and inside their own consciousness. In these circumstances, they gathered internal strength while building a shell of survival in the extreme reality of murder. Through their artworks, the personal experiences of the creator are interwoven within the historical story, expressing what was happening in their inner world while also constituting historical evidence.

The works in the exhibition reflect two faces of the work in hiding – a spiritual refuge and the documentation of reality. In the works of the children Jack (Kuba) Jaget and Nelly Toll, for example, the home and life that existed before the war were expressed; faith and identity were reflected in the work of Jacob Barosin, who testified that reading the scriptures in hiding had a great effect on him, and at this time he began to create initial sketches that he later used for the illustrated bible he created after the Holocaust.

The painter Felix Nussbaum and his artist wife Felka Platek went into hiding in occupied Belgium. In the fall of 1942, when they realized that the Gestapo was following them, they left their home and sought refuge with the sculptor Dolf Ladel. The couple stayed with him until March 1943, when the couple was forced to return to their previous home. The owner of the apartment, who was a member of the Belgian underground, hid them in the attic of the apartment, which he made sure to furnish for them while leaving the apartment itself empty in order to mislead the Germans in case they came to search.

In the crowded attic in Brussels, the Nussbaums tried to occupy themselves and overcome their fear by painting the objects and furniture around them. They could not use oil paint because the pervasive smell of turpentine would have given away their location. The exhibition features two of the still life paintings painted by Nussbaum in this short period, in which everyday objects are accurately described and recorded in their three-dimensional space, dated precisely: 20-27 March 1943. One of the works, The Kitchen in Hiding, depicts the corner of the room between a rough table or flower stand and the sink – the meagre kitchen utensils and single plant are visible testimony to their seclusion and their necessarily restricted field of vision.; the everyday objects are noted precisely and carefully in their three-dimensional from, as if the artist needed to be reassured of their physical presence. In Nussbaum's case, that also meant reassurance of his own existence. In June 1944, the couple was arrested following a tip-off, and deported to the Mechlen camp, from where they were sent on the last transport that left Belgium, on 31 July, to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Two days later, on August 2, 1944, they were murdered.

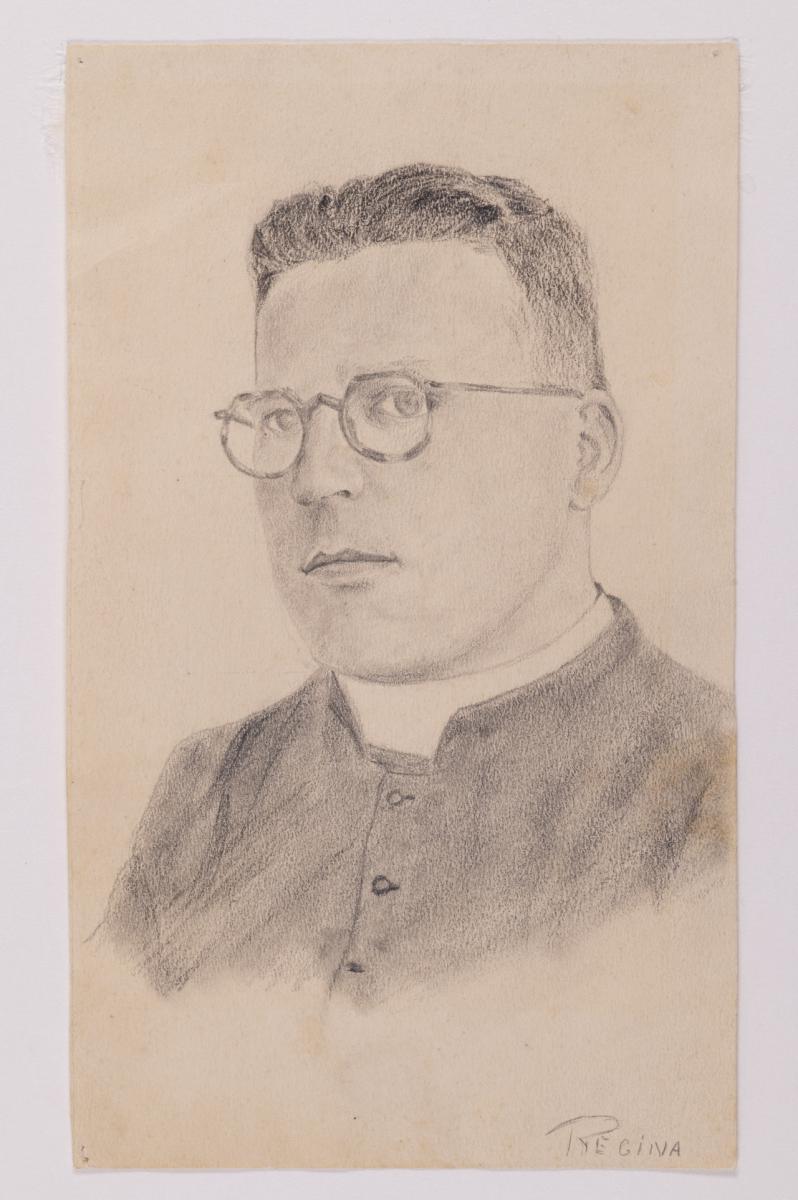

Regine Rotenberg Walbrum, who was born in 1925, records in her sketches two of her rescuers: the priest brothers of the Celis family. Hubert Celis from the Belgian town of Hemel helped find refuge for Regine's two younger brothers, 13-year-old Wolfgang and nine-year-old Sigmund, at the home of his brother, Rev. Louis Celis; and he moved 16-year-old Regine and her two-year-old sister Sonia to the home of the priests' father, 80-year-old Joseph Celis. On 29 October 1942, following a tip-off, the parents were caught and sent by train to Auschwitz, to their death.

While she was in hiding, Regine painted a number of portraits, including of the Hubert and Louis Celis. Following a tip-off, on 3 May 1944, Regine was arrested at the Celis home. Coincidentally, she was sitting and drawing at the time. The elderly man insisted that Regine was a member of his family, and even tried to resist her arrest by force, but to no avail. Regine was taken away and later sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where she was forced to clear corpses. In January 1945, she sent on a death march to Ravensbrück and from there to Malchow and Leipzig, where she was liberated by the Red Army. A few months later, she returned to the home of the Celis family, where she was reunited with her three siblings. In 1980, their rescuers were recognized as Righteous Among the Nations.

In the works of those who were forced into hiding, both artists who were educated in their field and those who were taking their first steps in painting, a strong urge to document the reality they experienced and to commemorate it – the hiding place and its surroundings, their rescuers and also those around them who shared the hiding place with them – is evident. In other cases, the creators sailed into the realms of the imagination, such as the world of fairy tales, the stories of the bible, painting portraits of their loved ones and depicting their past. In both cases, it seems that the works in hiding answered the artists' need to cling to a familiar and stable anchor in difficult and dark days characterized by uncertainty and constant existential danger. This need is the motif that runs through the works in the new exhibition.