Yad Vashem Archives

Pictured: Michel Razymovsky, Georges Sztrum, Arnaud Marcouse, Georges Jacob and Norbert Bikales.

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum #38285

Courtesy of Norbert Bikales

Their gaunt faces and the haunted look in their eyes reflect the reality that they were living in. Many men fled the town with the approach of the Germans in 1939. More men were murdered when the Germans arrived. Wieliczka became the only town with an all-female Judenrat. Women were also assigned to forced labor until the men returned. On 26 August 1942, a large-scale Aktion occurred during which many Jews were murdered, while the majority were sent to the Belzec death camp.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives

Yad Vashem Artifact Collection

Donated by Alberto Corcos, Herziliyah, Israel

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, 1486/1431

A banner proclaiming "Am Yisrael Chai" (May the People of Israel Live), a flag of Israel and and flag of the United States of America are hung above two posters.

The top poster contains an image of a Swastika being broken.

On the lower poster, the words "May his name and his memory be erased" appear above an image of Hitler behind bars.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives

A sign that was hung for the Purim parade in the Landsberg DP camp in 1946

The poster reads, "'Jews will not have Purim any more.' Said Adolf Hitler in 1945"

Yad Vashem Photo Archives

The Central Historical Commission of the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in the American occupation zone, Munich

By 1946, approximately 250,000 Jews were living in Displaced Persons camps in Germany, Austria and Italy. The survivors managed to organize a vibrant Jewish life for themselves, which incorporated educational and cultural activities, religious observance and political activism.

This photograph was donated to Yad Vashem by Reuven’s daughters as part of the Gathering the Fragments Campaign.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives

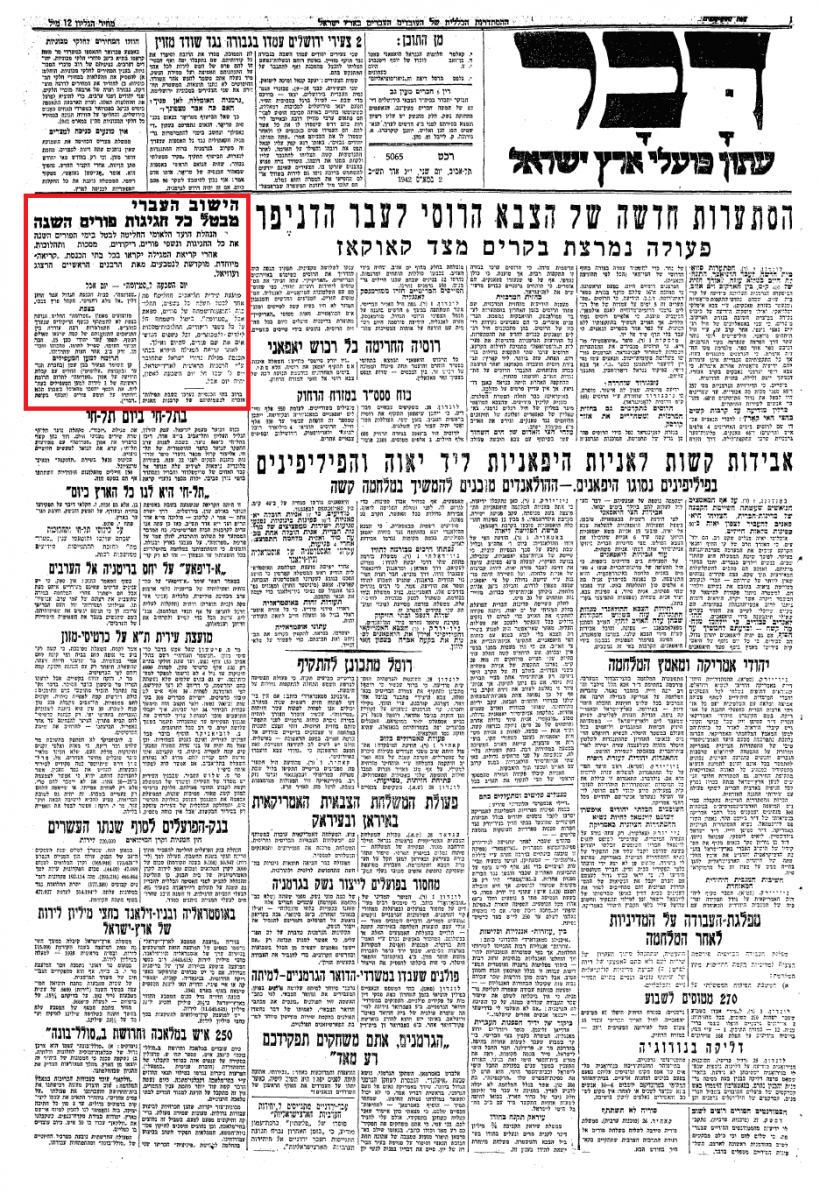

An article in the Dvar newspaper on 2 March 1942 announces that all Purim celebrations had been cancelled by the Yishuv's national committee in the wake of the sinking of the Struma. There will be a special reading of Megillat Nedudei Yisrael (Scroll of Israel's Wanderings) which will be composed by Chief Rabbis Uziel and Herzog to follow the traditional reading of the Book of Esther on Purim. The National Committee also called for the Jews of Eretz Israel and the Diaspora to hold a day of mourning and national protest on the seventh day after the tragedy.

Yad Vashem Archives

The holiday of Purim is approaching; traditionally one of the most joyous holidays in the Jewish calendar. It is said that when the Jewish month of Adar begins, we should "increase in happiness,"[1] but how do we relate to this imperative to be happier in times of trouble and in times of uncertainty when people are sad or in mourning?

I am going to address this question by looking at the different ways that Jews celebrated or marked the holiday of Purim during and immediately after the Holocaust. It is customary to hold celebrations on Purim, to dress up, and perform plays and parodies; one response is to try to maintain at least some sense of normality for children. Even in the Lodz ghetto, some of the children were dressed up in costume for a Purim celebration. At the Chabannes Children's Home in France, staff made an effort to preserve the children's Jewish identity; teaching them about the Sabbath and Jewish holidays included dressing the children in costume for Purim. Despite attempts to maintain activities that recall happier times, looking at the faces of the children in a photograph from a Purim celebration in Wieliczka, Poland, 1942 it is clear that their gaunt faces and the haunted look in their eyes reflect the reality in which they were living.

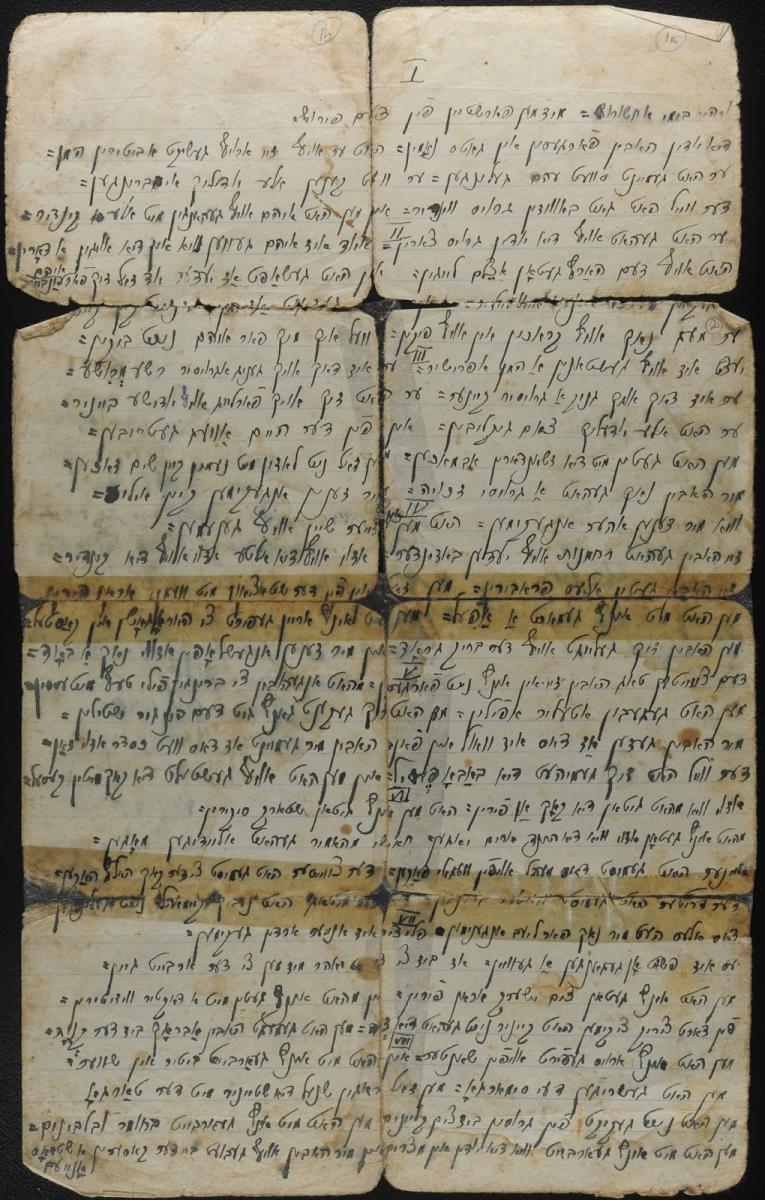

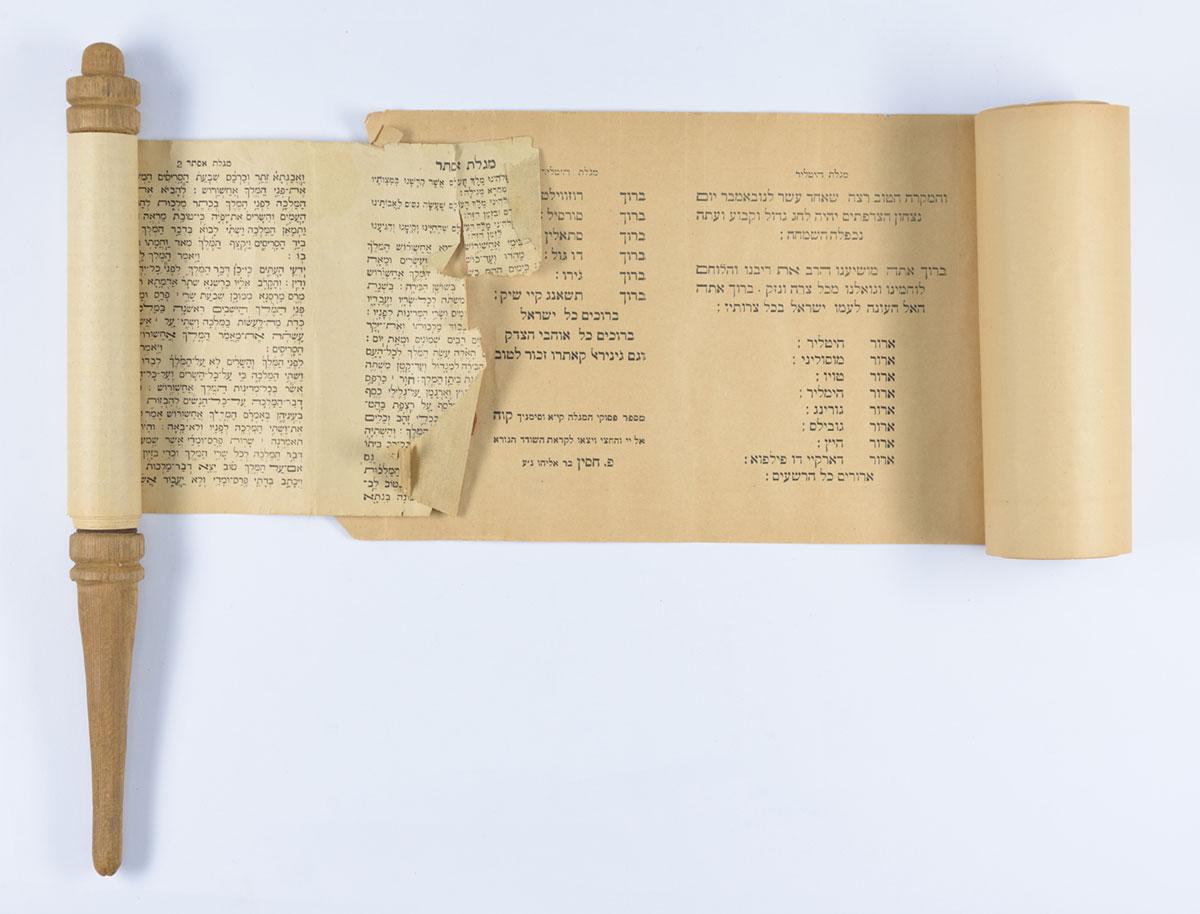

But what about the adults – how did they celebrate or mark the day? One of the central commandments of Purim is the reading of the Book of Esther known as the Megillah. Yad Vashem's archives contain two documents that related the events of the Holocaust but in the style of the megillah. The authors of the two documents took different approaches to this question.

One was handwritten by Zvi Hershel Weiss in 1943 at the Ilia camp in Transylvania, combining the story in the Book of Esther with the story of the inmates. He wrote the text in order to uplift the mood of his fellow Jews imprisoned alongside him and recited it using the traditional Purim cantillations.

The other document is the “Megilat Hitler,” written in Casablanca, Morocco in 1944. Spread over seven chapters and written in the style of Book of Esther, Prosper Hassine, a scribe and teacher in Casablanca, related the events of the Holocaust, from the rise of Hitler to power, through the occupation of Europe and climaxing with the murder of the Jews and the plunder of their property. The final three chapters, written after the liberation of Morocco, are dedicated to the history of North African Jewry and their liberation by the Allies.

The events related in Megillat Hitler parallel the events of the traditional Megillat Esther and reflect the sense that the Jewish people had once again experienced what the Jews of Shushan experienced when Haman set out to destroy the Jews of the Persian Empire. However, in spite of the similarities, Hassine stresses in his preface to Megillat Hitler that it is not a story of joy, since it does not have a happy end. He writes that the Megillah should be read with a serious demeanor while remembering the victims.

Beyond the question of how to perform the specific customs of the day remains the challenge of "increasing in joy". Can, and should, it be done?

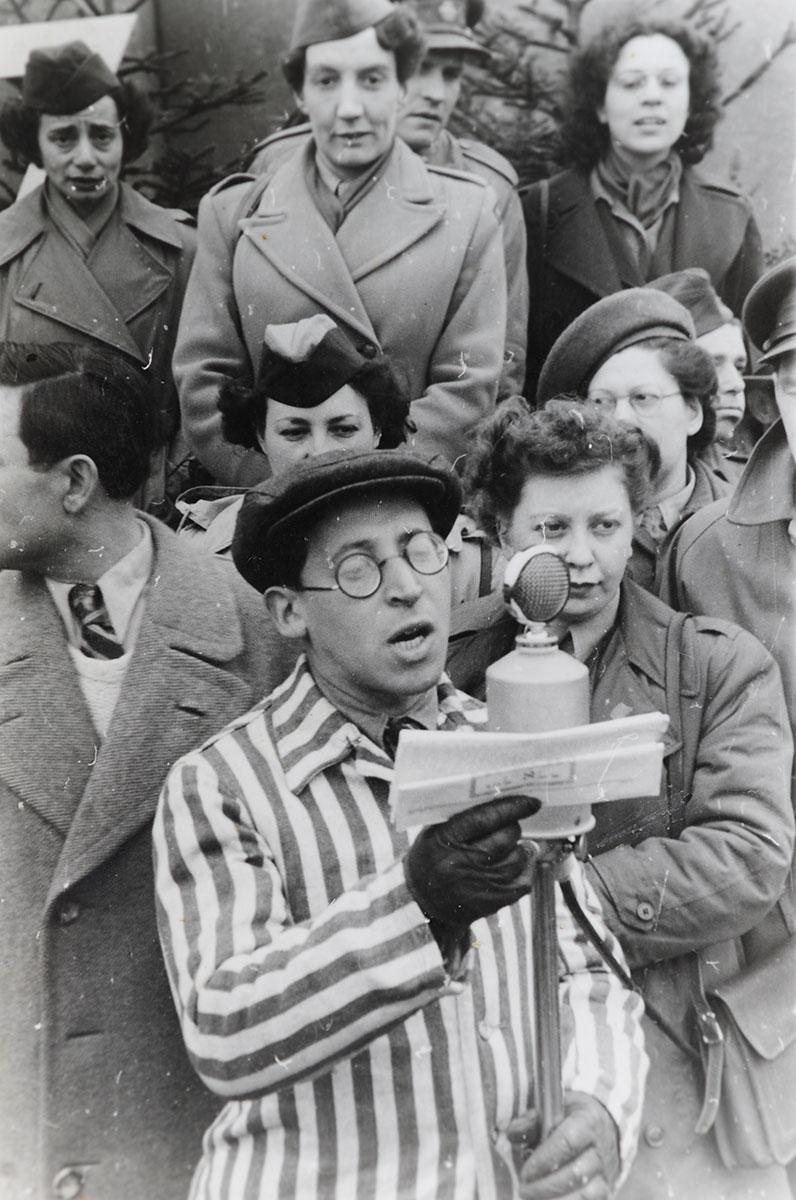

The Displaced Persons Camps after the war served as temporary transit stations for the survivors, it was there that they also started to cope with the enormity of their loss as they 'returned to life'. Despite the difficult living conditions, the DP camps had a vibrant cultural, political and religious life.

Photographs of the Purim holiday from the Landsberg DP camp (c. 1946) show expressions of triumphant celebration at the defeat of Hitler and the Nazis, drawing on comparisons or conflations of the Purim story and the Holocaust. Survivors in the DP camp made a mock-tombstone for Haman (the antagonist of the Purim story who had tried to annihilate the Jews in the ancient Persian empire) and Hitler. Posters proclaiming "Am Yisrael Chai" (May the People of Israel Live) were hung above images of a Swastika being broken and Hitler behind bars. Other posters proclaimed a quote attributed to Hitler, "The Jews will have no more Purim," an aspiration or a prophesy that had clearly not come to pass.

Also in the Landsberg DP camp, Reuven Jamnik read the megillah while wearing a striped inmates uniform, highlighting the distinction between living – only a short while ago – in the camps under threat of extermination, and the present, standing as a free man and reading from a Megillah about the salvation of the Jewish people.

But in the immediacy of a tragedy, at the height of mourning, overt celebration can indeed be deemed inappropriate. In December 1941 the Struma sailed with some 780 Jews fleeing Romania, hoping to make their way to a new life in Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine). The ship was sunk a week before Purim 1942. Only one passenger survived. This was the largest maritime disaster suffered by the Ha'apala (illegal immigration) operation and news spread rapidly.

In Eretz Israel, all Purim celebrations scheduled for the following week were cancelled by the Yishuv's National Committee; a day of mourning and national protest was called and most synagogues held memorial services for the victims of the Struma. That Purim, after reading the Megillah, congregations read the Megillat Nedudei Yisrael (Scroll of Israel's Wanderings), composed by Chief Rabbis Uziel and Herzog for the occasion.

[1] Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Taanit, p29a